Future Tense: Hamed Owais and the Aswan High Dam

by Kristina Centore

In 1952, tensions that had long been implicit within Egypt’s complex colonial power structures were brought to the fore. The 23 July Revolution of 1952, which led to the political rise of Gamal Abdel Nasser, succeeded in both overthrowing the British occupation that had been in place in Egypt since 1882 and in refuting the wide-ranging French influence that had existed since Napoleon’s invasion in 1798. The 1952 revolution, followed soon after by President Nasser’s nationalization of the Suez Canal in 1956, marked a critical turning point in the history of modern Egypt and became an impetus for decolonial revolution throughout Africa and Asia. Egyptian nationalism, as well as the broader pan-Arabism and the Non-Aligned Movement that it galvanized, signaled that freedom from a long history of control by colonial powers was finally possible.1

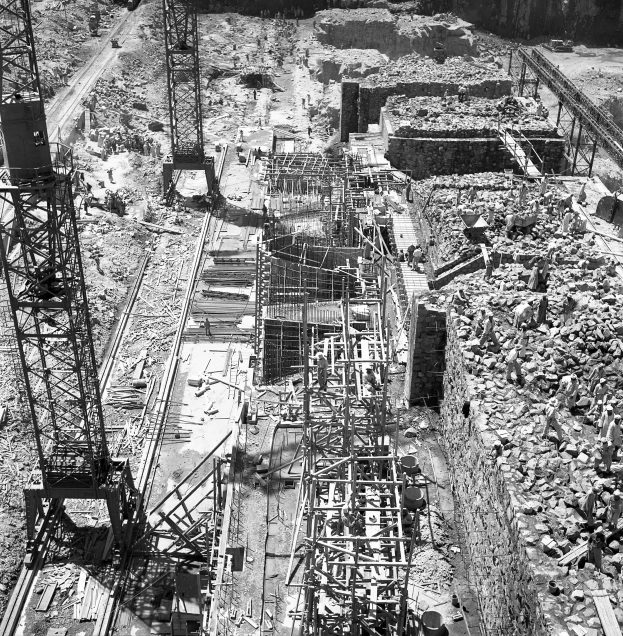

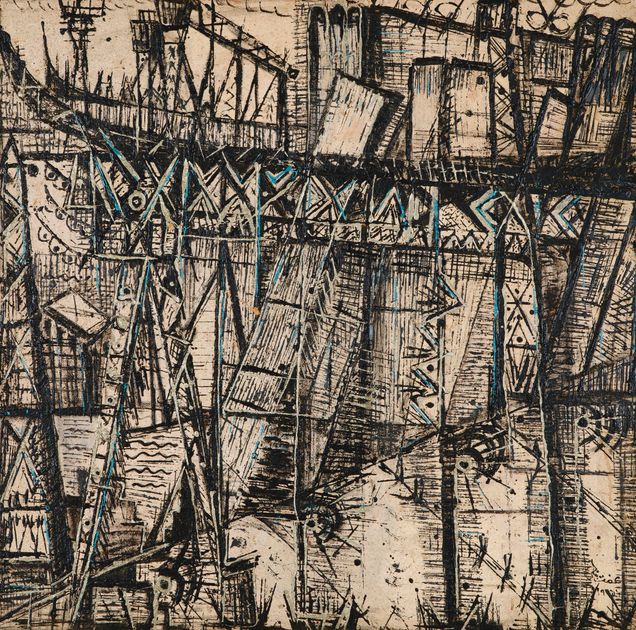

The nationalization of the Suez Canal removed the waterway from Western control, and had occurred in order to raise revenue for the building of the Aswan High Dam (al-Saad al-Aali) (fig. 1). The High Dam was to secure Egypt’s self-sufficiency by impounding the Nile River in a vast reservoir, coined Lake Nasser, in order to convert its flowing water into hydroelectric power that would contribute to the newly sovereign nation’s independence. Initiated during this time of optimism, the construction of the High Dam was depicted widely in painting, photography, and other media. The Egyptian government provided sponsorships and grants to artists to render both the dam and the villages of Nubia, sited on the land to be submerged.2 Though government sponsored, this program allowed for a multiplicity of artistic styles and even subtle critiques of the state to come through in the works.3 For instance, in Aswan (1964), Ragheb Ayad’s (1892–1982) depiction of the dam, the viewer is placed near ground level, slightly pulled away from the midst of the construction by a mass of workers (fig. 2). Ayad’s painting does not glorify the worker in the name of the state, but rather—connecting the worker to history—evokes the backbreaking work of building the ancient pharaonic monuments.4 However, unlike the laborers in Ayad’s painting, who toil in the shoveling of earth, workers in At the Aswan Dam (1965) by the Egyptian social realist painter Hamed Owais (1919–2011) are instead integrated with the futuristic machinic parts that make up the electrical towers of the power station adjacent to the dam (fig. 3).5 At the Aswan Dam captures how social collectivity during these revolutionary years was redefined by technological imperatives connected to the building of the High Dam.

Owais’s painting depicts the construction of the dam in a style that shows the influence of Mexican muralism and edges towards the geometric compositional structure of a constructivist photomontage.6 Through Owais’s mechanized forms and collapsing of space into nearly flat geometry, the overall appearance of At the Aswan Dam bears a resemblance to the systems that governed the electrical grid generated by the dam’s turbines.

Constructed between 1960 and 1970, the building of the dam harnessed Soviet-engineered modern technology (and was ultimately largely financed by the USSR as well as designed by the Hydroproject Research Institute in Moscow, or “Gidroproekt”) to generate hydroelectric power and, in the process, control the flooding of the Nile that had occurred annually for millennia.7 This intervention was both an intrusion that reshaped the natural landscape of Egypt and a radical blow to the lived experience of the Nubian people, who were forced to evacuate their villages on the banks of the Nile to make way for the dam.8

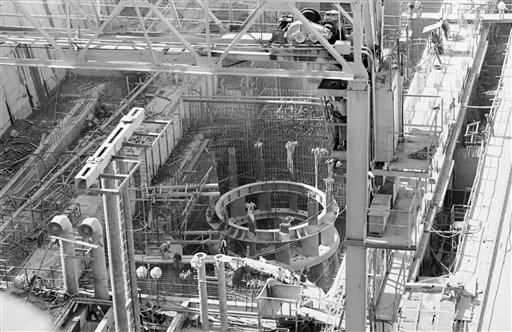

The application of Soviet expertise to the project included the construction of a control room, located deep within the dam itself, which regulated the processes of the dam’s electrical substations (fig. 4).9 Similar to the internal workings of the dam, the lines and connections of Owais’s electrical towers are interwoven in such a way as to be almost schematic, like a circuit board large enough to encompass the human figure. At the same time, Owais’s landscape also contains a subtler but no-less-real invocation of the processes of an engineered modernity. The smooth ultramarine blue of Owais’s rendering of the reservoir masks any sign of the Nubian villages that were in actuality submerged beneath it, raising the question of how Owais may have rationalized this concealment. In the landscape itself, we see new construction that completes the erasure of the villages. These structures, which may be temporary dwellings or day shelters for the workers, dot the riverbank along with construction vehicles and equipment. There also appears to be a tower for a telephone line with perhaps a bullhorn attached to it to announce the start and stop of work.10 The scene eschews the possibility of a singular perspectival reading, appearing untethered from a terrestrial logic; the scopic confusion of this fragmented, re-imagined modern landscape reconfigures space and is infused with impositions of timekeeping and labor.11

The attempt to harness the power of nature by way of the dam had unintended effects, as was made apparent by the massive flooding of the Temple of Ramses II (1260–50 BCE) and other ancient monuments, that was caused by the project.12 The deluge sparked a massive intervention by UNESCO to disassemble, relocate, and reassemble the pharaonic structures in new locations on the shores of Lake Nasser.13 Similar to this remapping of history, the dam itself was comprised of granite from Aswan’s geologically unique rock formations.14 This granite, likely visible as the sandy-brown rocks in the foreground of At the Aswan Dam, was quarried and removed from its location in the geological record in a physical process that historian Nancy Y. Reynolds relates to the idea of time turned upside-down.15 Such a sense of dislocation echoes throughout the compositional fragmentation of Owais’s forward-looking vision.

The building of the dam replaced these ancient sites with a giant power station that extended the electrical power grid throughout Egypt (fig. 5). Because of the dam, it became a new normal for the average Egyptian home to have a television set and to be connected to new experiences of the simultaneity, to borrow from Benedict Anderson, of national broadcasts.16 As Elizabeth Bishop surmises, these broadcasts formed a “control room” in a different sense, spreading condoned values through the government’s choice of programming.17 In this way, the dam contributed to a new definition of Egyptian national identity at the same time as its ripple effects impacted the politics and culture of the greater Arab world.18 The dam itself certainly occupied a prominent place in popular culture. In the words of art historian Avinoam Shalem, the ’60s in Egypt were “born, so to speak, under the sign of the Aswan Dam.”19 Revolutionary songs about the dam were broadcast continually over the radio, and Nubian men could be seen with its image embroidered on their skullcaps.20 Many international dignitaries and even Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir came to see the dam firsthand.21

The construction of the dam was transformative in many, perhaps unintentional, ways. Art historian Anneka Lenssen suggests that the apparent propagandistic goals of Owais’s At the Aswan Dam are tempered by the loss of a human element that had been a crucial part of Owais’s previous works.22 In 1947, after returning from studying at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando in Madrid and subsequently taking a position at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Alexandria, Owais had co-founded the Egyptian Group of Modern Art along with other well-known Egyptian artists such as Gamal el-Sigini, Gazbia Sirry, Zeinab Abdel Hamid, Salah Yousri, and Youssef Sida.23 In a 1984 interview, Owais described the Group of Modern Art to Karnouk as follows: “We believed that revolutionary ideology should be reflected in art. We, the Group of Modern Art, rejected ‘surrealism,’ because it was essentially rebellion, or an art which did not aim at the consciousness of the people at large.”24 Here, Owais emphasizes his stance that art should focus on social collectivity, with the goal of evoking the essential inner spirit of the Egyptian people. This goal is made particularly visible in Owais’s Factory Workers (1953). Though in this painting workers are shown looking somewhat tired and subdued as they file home from a day’s labor, Owais’s realism allows for a sense of their character and dignity to show through.

Fundamentally, the Group of Modern Art also rejected the idea of the past as a tool to shape the future and instead embraced the new and the now as a concrete aspect of Egypt’s revolutionary moment.25 At the Aswan Dam extends this notion a step beyond Owais’s earlier humanist representations. The integration of the worker with both the physical and symbolic dimensions of infrastructure in At the Aswan Dam reconfigures Owais’s focus on social projects to one that emphasizes a greater reliance on technology and systems. The workers depicted in the painting, two with their faces concealed by their helmets and one with face obscured by orange goggles, may well have been Nubian men from the now-absent village below and are incorporated into their new environment as the old one disappears.26 Yet, these workers do not “speak,” and like any other individuals, would have viewed the project in complex ways.27 The promise of the dam and its aura of progress was surely pervasive and brought with it new possibilities of modernity and freedom from the past.

These possibilities, however, brought liberation into negotiation with the real-world effects of the dam. Effat Naghi’s (1905–1994) The High Dam from 1966 provides an apt metaphor for the disjuncture between the plans for the dam and the myriad physical consequences of its construction (fig. 6). Naghi depicts the dam’s scaffolding as an intersecting, tenuous mass of lines that perhaps indicates the ambiguities and precarities of the project itself.28 The dam as an ambitious plan that would bolster Egypt’s freedom soon materialized as a massive work of infrastructure that signaled the integration of the newly independent nation with large-scale technological systems.29

A version of this text is included in Centore’s MA thesis, “Technology, Time, and the State: The Aesthetics of Hydropower in Postcolonial Egypt” (Tyler School of Art and Architecture, Temple University, May 2020).

____________________

Kristina Centore

Kristina Centore is a writer and artist based in Philadelphia, PA, USA. She is a May 2020 graduate of the Master’s program in Art History at the Tyler School of Art and Architecture. Her research focuses on technology, temporality, and political non-alignment in art during the Nasser years in Egypt.

____________________

Footnotes

1. For a history of non-alignment, see Christopher J. Lee, ed., Making a World After Empire: The Bandung Moment and its Political Afterlives (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2010).

2. Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi, “The Politics of Egyptian Fine Art: Giving a Voice to the People,” The Century Foundation, May 16, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/politics-egyptian-fine-art/?agreed=1.

3. Al Qassemi, “The Politics of Egyptian Fine Art.”

4. This observation is based on a description of the work in “Aswan, Ragheb Ayad,” Barjeel Art Foundation, accessed February 20, 2020, https://www.barjeelartfoundation.org/collection/ragheb-ayad-aswan/.

5. Alternate spellings of the artist’s name include “Hamed Ewais,” which is, for example, used by the Barjeel Art Foundation as well as on listings for sales of the artist’s work by the auction house Christie’s, and “Hamed Oweis,” which is used in Liliane Karnouk, Modern Egyptian Art 1910–2003 (New Revised Edition) (Cairo and New York: The American University in Cairo Press, 2005). For a description of At the Aswan Dam, see Anneka Lenssen, “Exchangeable Realism,” in Postwar: Art Between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945–1965, ed. Okwui Enwezor, Katy Siegel, and Ulrich Wilmes (London and New York: Prestel Publishing Ltd., 2016), 430–435.

6. See, for instance, Aleksandr Rodchenko’s propagandistic photo series in the Soviet periodical USSR in Construction (SSSR na stroike), which was mainly active in the 1930s. I thank Dr. James Merle Thomas for pointing me in this direction. More on USSR in Construction, in comparison to contemporaneous American New Deal photography, can be found in Timothy A. Nunan, “Soviet Nationalities Policy, ‘USSR in Construction,’ and Soviet Documentary Photography in Comparative Context, 1931–1937,” Ab Imperio no. 2 (April 2010): 47–92.

7. Avinoam Shalem gives the dates for the construction of the dam as 1960 to 1970 in “Man’s Conquest of Nature: Al-Gazzar, Sartre, and Nasser’s Great Aswan Dam,” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art no. 32 (Spring 2013): 25. For more on the role of the Soviet government in the construction of the dam, see Elizabeth Bishop, “Control Room: Visible and Concealed Spaces of the Aswan High Dam,” in Landscapes of Development: The Impact of Modernization Discourses on the Physical Environment of the Eastern Mediterranean, ed. Panayiota Pyla (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013), 74.

8. The Nubian people are a Muslim African population that are often considered to be directly descended from pharaonic Egypt. See Anne M. Jennings’s 1995 anthropological study of a Nubian community north of Aswan (for whom, therefore, eviction was not obligatory during the High Dam construction) for more information on Nubian culture and architecture (Anne M. Jennings, The Nubians of West Aswan: Village Women in the Midst of Change (Boulder and London: Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc., 1995)). According to Jennings, fifty thousand Nubians were resettled in Kom Ombo as a result of the High Dam construction; Jennings, The Nubians of West Aswan, 28.

9. Bishop, “Control Room,” 81.

10. I thank Dr. Emily Neumeier for pointing out the presence of the bullhorn, which signals the notion of timekeeping.

11. Pertinent to the notion of temporalities in Egypt are On Barak’s analyses of the effects of the imposition of the Gregorian calendar over the Hijri with the establishment of the telegraph in Egypt; On Barak, “Outdating: The Time of ‘Culture’ in Colonial Egypt,” Grey Room no. 53 (Fall 2013): 6–31.

12. Shalem, “Man’s Conquest of Nature,” 25.

13. Ibid., 26.

14. Nancy Y. Reynolds, “Building the Past: Rockscapes and the Aswan High Dam in Egypt,” in Water on Sand: Environmental Histories of the Middle East and North Africa, ed. Alan Mikhail (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 194–197.

15. Ibid., 182.

16. For more on the dam and its connection to television, see Bishop, “Control Room,” 81. Similarly, Benedict Anderson describes the “simultaneity” of the national press, in which the same information is read by all within a nation’s boundaries, as a defining characteristic of how national identity is constructed; Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 2006), 24–25.

17. Bishop, “Control Room,” 81.

18. Here I combine Bishop’s assessment of the dam’s relationship to television with Shalem’s observations on the effect the dam had on culture overall; Shalem, “Man’s Conquest of Nature,” 21.

19. Shalem, “Man’s Conquest of Nature,” 25.

20. Reynolds, “Building the Past,” 187, 194.

21. Shalem, “Man’s Conquest of Nature,” 21–22; as Shalem relays, Sarte and de Beauvoir also viewed a celebrated painting, The High Dam by Abdel Hadi al-Gazzar, while in Egypt.

22. Lenssen, “Exchangeable Realism,” 434.

23. Nadia Radwan, “Hamed Owais,” Mathaf Encyclopedia of Modern Art and the Arab World, accessed April 2, 2020, http://www.encyclopedia.mathaf.org.qa/en/bios/Pages/Hamed-Owais.aspx.

24. Karnouk, Modern Egyptian Art, 80. Surrealism was a prominent art movement in Egypt during the interwar years and throughout WWII; see Sam Bardaouil, Surrealism in Egypt: Modernism and the Art and Liberty Group (London and New York: I. B. Tauris & Co. Ltd., 2017). Surrealist aesthetics were also employed by the Egyptian Contemporary Art Group, which included al-Gazzar, after WWII. Manifestos of the Contemporary Art Group are reproduced in English in Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents, eds. Anneka Lenssen, Sarah Rogers, and Nada Shabout (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2018), 113–116.

25. Karnouk, Modern Egyptian Art, 78.

26. Here I take the idea that the Nubian men from the villages that were being destroyed were also employed in the dam’s construction from Reynolds, “Building the Past,” 194.

27. Here I reference Gayatri Spivak, “Can the Subaltern Speak?” in Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory, ed. Laura Chrisman and Patrick Williams (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), 66–111.

28. This observation is made in a description of the work on the Barjeel Art Foundation’s website; see “The High Dam, Effat Naghi,” Barjeel Art Foundation, accessed December 10, 2019, https://www.barjeelartfoundation.org/collection/effat-naghi-the-high-dam/.

29. For more on the environmental and social effects of the Aswan High Dam, see Patrick Kane, The Politics of Art in Modern Egypt: Aesthetics, Ideology, and Nation-Building (London: I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd., 2013), especially Kane’s discussion of “representations of the Aswan Dam in Egyptian arts as a discourse on the dialectical relation of the state, region, and labor” (p. 139) in Chapter 6: “Conflicts in the Arts Over Upper Egypt: ‘Abd al-Hadi al-Gazzar and His Contemporaries,” 139–171, and Timothy Mitchell, Rule of Experts: Egypt, Technopolitics, Modernity (Berkely, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 2002).