An Alameda of One’s Own: Race and Modern Subjectivity in a Portrait of Ramona Antonia Musitú y Valvide de Icazbalceta

by Rachel Bonner

In a portrait from 1793 by the painter Juan de Sáenz, the wealthy New Spanish woman Ramona Antonia Musitú y Valvide de Icazbalceta occupies an ambiguous space at the center of the composition, poised between a curtained void and an enclosed garden (fig. 1). While her extravagant accessories and the imported textile of her dress communicate her wealth and cosmopolitanism, sustained analysis suggests that Musitú’s self-fashioning is primarily achieved through a racialized discourse of land-ownership and management, as well as access to specialized knowledge. In advancing this argument, I read Musitú’s portrait as a relatively modern articulation of subjectivity. Such an interpretation may complement, rather than undermine, religious readings of the enclosed garden space.1 While pointing to the ways that Sáenz’s portrait of Musitú may be superficially empowering, I argue that the image contributes to a discourse of racial superiority into which Musitú’s partial agency can be subsumed and which, ironically, continues to affect how Spanish colonial works such as the Portrait of Ramona Antonia Musitú y Valvide de Icazbalceta and Her Two Daughters are interpreted and (de)valued.

In Sáenz’s portrait, Musitú is positioned in the central foreground of the canvas so that her body divides the composition and bridges its two halves. While sustaining eye contact with the viewer, she appears to step forward from the curtain that separates the foreground from the abyss to her right; as if from an interior space she lays claim to the ornate garden behind her. This background both beckons and appears inaccessible to the viewer. The woman and her young daughters occupy a significant percent of the composition, and the viewer’s eye is drawn to the profusion of finery and flowers with which the figures are adorned. As the canvas is animated by diagonal lines and intricate details, Musitú’s hat is one of the focal points of the composition; its two large feathers lend a sense of balance to the painting and its abundance of fresh flowers echo both the plants that are being cultivated in the garden below and the one that seems to spring from the palm of the older daughter. The focus on foliage and ornamentation links the sitters visually and conceptually to the garden itself; this is underscored by the figure of the youngest daughter clutching a silver watering can, whom Musitú grasps by the wrist. Musitú and her daughters are presented as having privileged access to the gated property, while their alignment with material objects also suggests that they constitute a component of its enclosure; the subjects are framed by a void-like section of the canvas that hints simultaneously at access and impenetrability.

While spatial ambiguities in colonial paintings are often dismissively attributed to the artist’s lack of academic training, the particular vantage point of the background in this portrait has ample precedent in viceregal images of New Spanish cities and gardens. As art historian Ilona Katzew explains in the case of representations of Mexico City’s Alameda Park, this aerial perspective is significant as a depiction of what she calls “Pinturas de la tierra,” or paintings of the land, which have come to epitomize eighteenth-century innovation in New Spanish painting.2 These works are characterized by the type of encompassing bird’s-eye-view that can be seen in Saenz’s portrait of Musitú and that frequently incorporates a dizzying level of meticulous detail alongside an emphasis on local topography and subject matter.

An example of these “Pinturas de Tierra” is Manuel de Arellano’s 1709 The Transfer of the Image and Inauguration of the Sanctuary of the Virgin of Guadalupe, which offers an interesting point of comparison (fig. 2). Arellano’s painting constitutes a view of the outskirts of Mexico City that is so exhaustive as to be paradoxically disconcerting and elusive. Significantly, this work and others like it emphasize regional features of the landscape in ways that facilitate proto-nationalist sentiment.

The painting features the elaborate chapel built in 1709 to house the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe. This famous image, the result of a miraculous apparition of the Virgin Mary to the indigenous laborer Juan Diego in Tepeyac, became a focus of Mexican national identity in the independence period and beyond. As scholar and curator Ronda Kasl notes, The Transfer of the Image and Inauguration of the Sanctuary of the Virgin of Guadalupe includes an inscription proclaiming that the painting is a “true map” along with a key featuring seventeen numbered locations, many of which would have particular resonance to viewers of Spanish ancestry.3 The seventeenth of these itemized features, for example, is a depiction of Saint Felipe de Jesus, the first Creole (an American-born individual of Spanish descent) to be canonized for martyrdom.4 The perspective of the painting allows for a sense of all-encompassing access, but would have particular significance for a creole individual familiar with the more intricate details of the landscape and local culture.

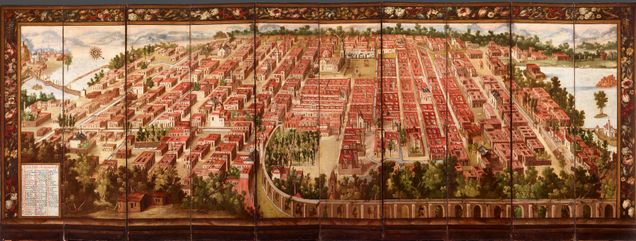

Another image that uses the same visual rhetoric, in terms of perspective and richly detailed depiction of territory, is a seventeenth-century biombo describing the conquest of Mexico. This folding screen, inspired by Japanese imports, features extraordinarily detailed oil on canvas landscapes in aerial perspective. The front side of the screen employs a dark palette and consists of ten panels depicting the Spanish conquest of Tenochtitlan, now Mexico City (fig. 3). In the lower left corner of the screen is a map key, which labels nine historic scenes spanning from the first meeting between Cortes and Moteuczoma to later rebellions against the Mexica tlatoani, or indigenous officials.

The reverse side of the screen (fig. 4) maintains the aerial perspective, but depicts a much brighter, more grid like scene of Mexico City as the newfound capital of the Spanish viceroyalty. The biombo as a whole, as scholar Kevin Terraciano explains, depicts the transformation from “a chaotic, crowded site of conflict” to “a spacious, orderly city.”5 This observation has a racial dimension that recalls Brenna Bhandar’s theorization of the circular, violent logic that stems from the relationship between the “proper” use of land and a weaponized concept of race, where non-European approaches to land management are denigrated and used as a justification for dispossession.6 In this case, the darker palette that characterizes the conquest side of the biombo appears significant, and potentially meaningful to the wealthy Creole or Spanish individual who lived with this screen and whose own sense of subjectivity would be supported by its version of history.

An anonymous biombo entitled Allegory of New Spain,7 from the early eighteenth century, presents an environment similar to the one described in the portrait of Musitú. This image depicts what the art historian Richard Kagan refers to as a “pleasure park,” or a specifically “Creole space” for leisure and recreation.8 The image suggests the significance of parks and gardens in the New Spanish imaginary, a theme that is reinforced by Kagan’s reading of another anonymous oil on canvas work from the early eighteenth century. Vista de la Alameda de México depicts an aerial view of Mexico City’s Alameda Park, a cultivated green space, located on the outskirts of the city, with a central fountain from which tree-lined walkways radiated (fig. 5). This symmetrical, geometric enclosure is presented as “a refuge from urban life”9 for the city’s Creole elite, although, as Kagan points out, its bucolic connotations are complicated by the inclusion of a stake at which Jewish victims of the Spanish Inquisition were burned. This dimension of the work is highlighted within the map legend in the painting’s lower right corner and suggests that the Alameda represented “a place indicative of the order, in the sense of policía, that Creole writers associated with the capital of New Spain.”10

Another illuminating example is found in an anonymous casta painting of 1775. Casta, or caste, paintings are a genre that flourished in eighteenth-century New Spain. They were pseudoscientific taxonomic works, which aimed to illustrate and label all the possible results of miscegenation in the viceroyalty. These images, which suggest both diversity and order, were created for and adorned the homes of Spanish and Creole individuals and were often taken back to Spain as souvenirs of the colonies. As such, they had a symbolic relationship to New Spain; their pseudo-scientific categorization represented an attempt at intellectual mastery and, by extension, control over a diverse society. This particular image, entitled De Alvina y Español Produce Negro Torna-Atrás, has a strikingly similar composition to that of Sáenz’s portrait of Musitú. In a slightly ambiguous balcony space on the left side of the foreground of the image, a wealthy man and a woman stand with their noticeably darker-skinned child. Behind and below them sprawls the intricately detailed, symmetrical space of the Alameda, where people (many of whom are dressed in bright shades of red that recall the cochineal curtains of the Musitú portrait) frolic and stroll in the shade.

In direct contrast to the portrait of Musitú, however, this casta image does not portray familial cohesion and the continuity of wealth and access. Rather, what is depicted is the resurgence (torna-atrás or turn-back) of blackness that has resulted from the union of a Spanish man and an “albina” woman, understood then to have been white passing but “one-eighth black.”11 As Kagan explains, the woman is shown kneeling in despair at what the viewer is supposed to understand as her loss of status and access to the exclusive space of the Alameda. Her husband, whose status as a white man is secure, turns away from her and their child in order to survey the expanse of the park.12 His position vis-a-vis the geometric space of the park, and his ability to know it through immediate, embodied observation, contributes to his unique subject position; while his Spanishness or whiteness allows him access, it is his physical presence in the Americas and established relationship to the land that gives him the sense of intellectual mastery encapsulated in his surveying instrument. Kagan’s reading of this image has significant implications for the interpretation of Sáenz’s portrait of Musitú. As a woman, Musitú’s whiteness is affirmed through the fact that her offspring hold the tools that will allow them to access, cultivate, and ultimately manage the garden space below. Whiteness, in its relationship to property, can thus be understood as a prerequisite for the kind of secular subjectivity that this image represents.

This reading is supported by several features of the space that are highlighted in the Musitú portrait; while less panoramic and comprehensive than the depictions of the Alameda and other similar cityscapes, the garden retains a sense of “rational cultivation” through its geometric layout. This rationality is undergirded by the fountain, which features recognizable subject matter. The fountain in the Musitú portrait echoes the cultivation around which the Alameda is centered and suggest a Versailles-like level of control over nature through its manipulation of water. It also features a prominent image of Neptune. As historian David Brading explains, references to classical mythology in the Americas became a way of articulating esoteric knowledge as well as a symbol of Creole identity, predicated on the eccentric but at one point widely cited argument that the Americas had an ancient connection to the lost city of Atlantis.13 In an effort to establish a history of the Americas that suited their complex aspirations, individuals who identified as criollo/a also attempted to draw parallels between the indigenous civilizations of the Western hemisphere and the civilizations of ancient Greece and Rome. The fountain in this portrait can thus be understood to function on multiple levels as a symbol of control over the land through the enforcement of the creole racial privileges.

That Sáenz’s portrait of Musitú partakes of the logic of whiteness in its relationship to elite identity can also be gleaned from comparison with a similar image about which significantly more is known. José de Páez’s Portrait of Francisco de Larrea y Vitorica and His Two Sons, Miguel José Joaquín and Pedro Nolasco José, painted in 1774, has strikingly similar subject matter. Francisco de Larrea y Vitorica, a finance administrator for the Marquisate of the Valley of Oaxaca who would eventually become its governor, is thought to have commissioned this painting while pursuing noble status (hidalguía) based on his Basque heritage. As noted by Ilona Katzew, this petitioning process involved testimonies of “blood purity” (limpieza de sangre).14 Katzew suggests that the portrait by José de Páez was likely produced as a component of the governor’s petition and that its emphasis on documentation and precision stems from this focus on legal evidence.

The labels that identify Francisco de Larrea y Vitorica and his sons refer back to the family crest adorning the upper right corner of the image; as Katzew notes, the “Basques and Cántabros who immigrated to the viceroyalties tended to be obsessed with emphasizing their place of origin in specific ways through inscriptions on portraits.”15 That the portrait of Musitú lacks such a lengthy inscription (the map-like key at the bottom includes only the full names of her two children, along with the date) supports the idea that she might have been a criolla, or a woman claiming Spanish descent born in the viceroyalties. Francisco de Larrea y Vitorica and his two sons occupy the foreground of their portrait. Like the Saenz portrait, in which Musitú anchors the image, Francisco de Larrea y Vitorica is painted at the center of the composition. With their tri-cornered hats tucked under their arms, the three men assume confident poses, cultivating a balance between a serene, self-assured stance and an upright formality. There is little in the way of the profusion of objects that characterizes the portrait of Musitú. Francisco de Larrea y Vitorica’s portrait features a large clock, which contributes to its commanding sense of order and precision, alongside a prominent coat of arms, to which the viewer’s eye is drawn by the sweep of the curtain in the background.

As I have argued, precision and the suggestion of temporality function differently, albeit to similar legitimizing effect, in the Portrait of Ramona Antonia Musitú y Valvide de Icazbalceta and her Two Daughters. While the authority of the clock is absent from Musitú’s portrait, time is not: the artist expresses a particular vision of continuity through land management, which is the thread that links the fountain in the background to Musitú’s young daughter’s watering can in the foreground. Whether this reflects gendered differences, Musitú’s possible Criolla (as opposed to Larrea’s Peninsular Spanish) identity, or both, I suggest that Juan de Sáenz’s portrait implies a sense of access to the land and its resources that is predicated on the articulation of racialized subjectivity and the fiction of whiteness. The relativity of race as a construct means that the viewer’s perspective determines whether or not Musitú is identified as a “white” woman in the twenty-first century, which in turn may condition the viewer’s assessment of the image’s modernity, ironically foreclosing an engagement with the facets of its meaning explored in this essay.

____________________

Rachel Bonner

Rachel Bonner is a third-year PhD student in Visual Studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz, where she focuses on transculturation and identity in the early modern Spanish Americas. She is an editorial board member and incoming assistant managing editor at Refract: An Open Access Visual Studies Journal.

____________________

Footnotes

1. The art and visual culture of the Spanish viceroyalties often subverts, or at least complicates, the religious/secular binary. The Virgin of Guadalupe, as both a religious figure and symbol of national identity, is one such example, as is Saint Rose of Lima. This is characteristic of early modern art on both sides of the Atlantic; Joseph Koerner’s famous reading of Dürer’s self-portrait of 1500, in The Moment of Self-Portraiture in German Renaissance Art, comes to mind.

2. Ilona Katzew, “Paintings of the Land,” in Painted in Mexico, 1700–1790: Pinxit Mexici, ed. Ilona Katzew (Los Angeles and Mexico City: Los Angeles County Museum of Art & Fomento Cultural Banamex, A.C., 2013).

3. Ibid., 294.

4. Throughout this article I use “Creole,” or the Spanish Criollo, as a period term, and do not intend to validate its connotations. By the eighteenth century, the label had a racial dimension, although “Spanishness” was originally conceived in religious terms, see María Elena Martínez, Genealogical Fictions: Limpieza de Sangre, Religion, and Gender in Colonial Mexico. (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008).

5. Kevin Terraciano “Competing Memories of the Conquest of Mexico,” in Contested Visions in the Spanish Colonial World, ed. Ilona Katzew (London and New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 75.

6. Brenna Bhandar, Colonial Lives of Property: Law, Land, and Racial Regimes of Ownership (Durham, NC, and London: Duke University Press, 2018).

7. Due to museum and office closures during the COVID-19 pandemic, I was unable to secure image permissions for most of the remaining works that I discuss in this article, many of which are in the same two collections.

8. Richard Kagan, Urban Images of the Hispanic World: 1493–1793 (London and New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), 161.

9. Ibid., 157.

10. Ibid., 157.

11. Ibid., 159.

12. Ibid., 159.

13. David A. Brading, The First America: The Spanish Monarchy, Creole Patriots, and the Liberal State 1492-1867 (London: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

14. Katzew, Painted in Mexico, 347.

15. Ibid., 347.