Mass of Saint Gregory: Artistic Disobedience in Early Modern Mesoamerica

by Emily Beaulieu

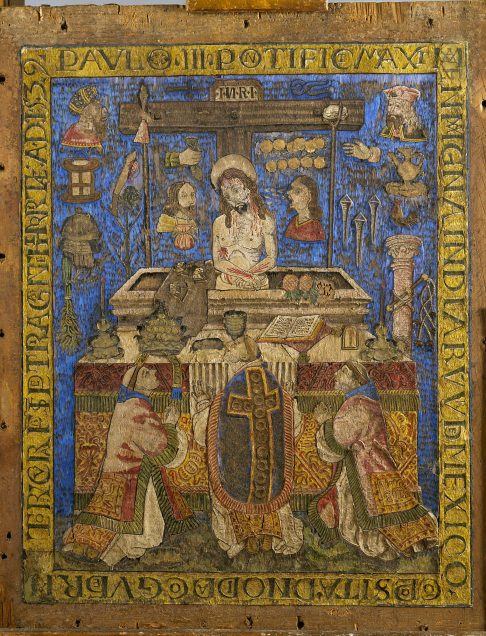

As the earliest surviving Christian featherwork of postcolonial New Spain, Mass of Saint Gregory offers an unparalleled site through which to examine an early moment of cultural exchange between the Aztec Empire and Spanish colonialists (fig. 1). Mass of Saint Gregory was made in 1539 for Pope Paul III under the direction of Franciscan missionary Fray Pedro de Gante and Mexica noble Don Diego de Alvarado Huanitzin.[1] The unique context of the featherwork’s production has invited scholarly debate over the nature of the cultural exchange between the work’s Indigenous artists and European patrons.[2] Scholars such as Alessandra Russo and Gerhard Wolf have questioned the validity of qualifying it as a true instance of “cultural hybridity.”[3] Instead, these scholars, among others, understand Mass of Saint Gregory as a work of Catholic propaganda touting a successful colonization—and Christianization—of the Nahua peoples against the reality of a failing conversion mission in Central America.[4] A product of “coercion” and a “fictive image” meant to reassure the pope, Mass of Saint Gregory—for many scholars—can bear no trace of a Nahua cultural identity.[5]

However, there is reason to believe that these absolutist conclusions obscure the complexity fundamental to moments of cross-cultural interaction, even ones born out of oppression and forced integration. Whether it was intended or not, Mass of Saint Gregory contributes to and is the product of a new, third culture that is neither purely Nahua nor purely Spanish. By inviting the active participation of Indigenous feather artists towards the creation of this piece, de Gante inadvertently opened the door for a more reciprocal moment of cultural exchange. The work’s Nahua artists hid an act of artistic disobedience behind the veil of compliance by integrating Nahua pictorial language within Christian iconography.

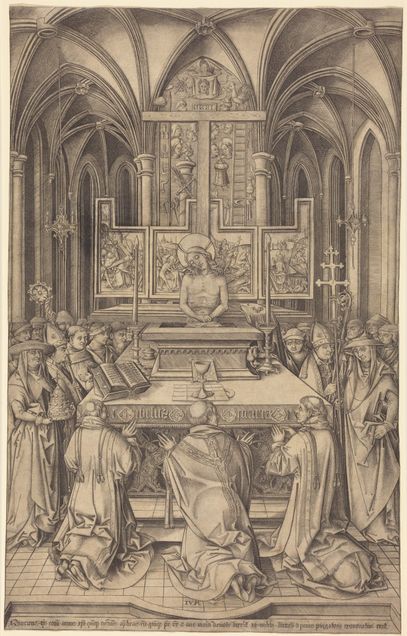

This paper argues that in the peculiar composition and iconography employed in the depiction of the instruments of the Passion—the Arma Christi—there is evidence for Nahua artistic disobedience in Mass of Saint Gregory. Upon close inspection of the featherwork, the arrangement of the Arma Christi deeply contrasts with the rendering on which the work was most likely based, a print by Israhel van Meckenem of the same subject (fig. 2).[6]

The composition of the Arma Christi found in De Gante’s Mass of Saint Gregory is, in fact, uncharacteristic of any European depiction of the subject and bears closer resemblance to the visual language traditional to the Nahua peoples. For this reason, I argue that the Arma Christi made in New Spain reveal a profoundly Indigenous interpretation of Christian symbols born of the Nahua visual culture. Such an act of Nahua artistic assertion represents further evidence to support the claim that early colonial Mesoamerican art contains moments of cultural resistance enacted by the Indigenous populations in the face of colonization and forced conversion.

For the Europeans, the symbols of the Arma Christi were used as mnemonic devices to aid the devotee in recalling important Christian tenets. This kind of mnemonic device closely aligns with the Nahua pictorial language employed in works of art made in the Aztec Empire.[7] Pictorial symbols used by Nahua artists took the place of the written word. Nahua symbols could be understood as abstract concepts, as the attributes to an object, or the sound of a word.[8] In this way, the practical function of the Arma Christi and Nahua pictographs were in essence the same. As Claire Farago argues, Spanish missionaries were well aware of this similarity and actively deployed the Arma Christi in cultural content produced for the purpose of conversion.[9] However, evidence from Mass of Saint Gregory suggests that the Nahua peoples utilized their pictorial linguistic tradition to assert their own cultural self-expression through such colonial artistic productions.

The assertion of Nahua identity in Mass of Saint Gregory is perhaps found most clearly in the treatment of the inner circle of the Arma Christi. In this inner subset, three of the four symbols relate directly to Judas’s betrayal of Christ: Judas with a bag of coins hanging around his neck, a hand holding another bag of coins, and finally a row of golden coins. These three symbols of Judas’s betrayal are all placed immediately surrounding the central figure of Christ. This pronounced emphasis on the figure of Judas in the Arma Christi is, indeed, extremely unusual. Though Van Meckenem includes similar symbols referencing Judas’s betrayal of Christ around the cross, they are not endowed with the same importance, either in size or centrality. Moreover, European depictions typically limit the symbols of Judas to one or two in number and tend to spread them throughout the entire composition. The fourth symbol of the inner Arma Christi would appear to reference the mockery of Christ by soldiers and onlookers.

The unique arrangement of these symbols can be explained by the Nahua pictographic tradition. In representations of Nahua pictographs, different symbols are arranged in space by their relation to one another.[10] The multiplication of the symbols of Judas—arranged around the figure of Christ—can now be understood as a Nahua-inspired method invoked to emphasize this apostle’s betrayal as the fateful event that would set in motion the crucifixion. The framing effect of the three symbols is further heightened by the inclusion of other instruments of the Passion: the spear to Christ’s right, the sponge filled with vinegar to his left, and, of course, the cross. Together, these instruments effectively frame the symbols of Judas and the figure of Christ.

Additional symbols alluding to Christ’s torments—betrayal, torture, and crucifixion—emanate outwards from the symbols of Judas. Following the Nahua pictographic tradition, these surrounding symbols are compositionally arranged as outcomes of the inner symbols (i.e., Judas’s betrayal). On the left-hand side of the cross, we have four symbols which allude to the subsequent arrest of Christ, including a helmet worn by the arresting soldier, a lantern, and a sword cutting off the ear of a servant accompanying the soldiers. Finally, the symbol of a tree is included below the sword. I believe this symbol to be a reference to the tree from which Judas hangs himself—an element usually featured in most scenes of the arrest. Below is a whip made of birch tree used to flog Christ. To the right of the cross are three symbols associated with Pontius Pilate, including his image, as well as a symbol of a hand and a basin which reference the moment in which Pontius Pilate washed his hands of the crime of sentencing Christ to death. Below these symbols, the featherwork features a column, whips, and nails which reference the Flagellation and Crucifixion of Christ. A pair of pineapples placed nearby, atop the sepulcher, stands out as a unique inclusion in this religious scene. Scholar Alessandra Russo argues that the addition of the tropical fruit both operates as a symbol for the Americas at large and takes the place of the bread or wafer usually depicted within this Eucharistic subject matter.[11] In this way, the pineapples cleverly allude to the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation, a central issue to the story of the mass of Saint Gregory.[12]

A final symbol would seem to reflect the Nahua tradition not only in its spatial relationship within the featherwork but also in its distinctly Nahua mode of representation. In the top left-hand corner of Mass of Saint Gregory is an image of one of Christ’s torturers sticking out his tongue in a mocking gesture. This type of figure carries great similarity with the depiction of the Nahua goddess Tlaltecuhtli (Earth Lord), often portrayed with a knife-like tongue evoking her bloodlust for human sacrifice.[13] Taking inspiration from a stock of Nahua motifs, the Indigenous artists impose their visual and cultural heritage onto a European Christian narrative.

The arrangement in which a multitude of mnemonic symbols alluding to the Passion of Christ radiate sequentially from the central figure represents evidence that the involved Nahua artists actively incorporated elements of their pictorial tradition into Mass of Saint Gregory. In bringing Indigenous patterns of thinking and methods of spatial visualization, the Nahua artists altered both the depiction of the Western subject matter as well as its traditional meaning. In essence, the work’s Indigenous artists partook in an act of artistic disobedience by asserting not only their visual tradition but also their spiritual perspective.

In the New Spanish version of the image, the sinner takes center stage alongside the savior. Mass of Saint Gregory, rather than emphasizing Christ’s sacrifice and the miracle of the Eucharist, finds its ultimate expression in Judas’s betrayal: the fateful event that would precipitate the death of Christ. This emphasis on the role of the sinner recalls the purpose of Nahua ritual sacrifice, which operated on the idea that the sacrificial victim was a placeholder for all who had sinned.[14] This idea is visually stressed through the framing of Judas and Christ together in the same space, as if the fates of sinner and savior were tied. The core emphasis placed on Judas’s role is almost entirely foreign to traditional Western approaches to the mass of Saint Gregory, but comes into focus when we examine it through the lens of the Nahua tradition of ritual sacrifice. Thus, this Christian featherwork produces not only a wholly original visual language, but also a new third set of beliefs, belonging to neither Spanish culture nor Nahua tradition but to an integrated yet distinct realm that would come to define the Indigenous customs of colonial Mexico.

Within the Arma Christi of Mass of Saint Gregory, Nahua artists assert their self-expression under the guise of Christian iconography, finding in the process a new voice. Out of the brilliant, iridescent feathers that make up their shape, these mystical symbols indicate the emergence of a “new” Nahua culture. Vibrant and dynamic in the face of colonialism, oppression, and conversion, this burgeoning creation would destroy its ancient gods only to resurrect them under a different name, carrying within them the lifeblood of the Nahua peoples into a new age.

____________________

Emily Beaulieu

Emily Beaulieu is a second-year master’s student in art history at Tufts University. She specializes in Italian Renaissance and Baroque art, with a particular interest in Caravaggio and art theory of the seventeenth century. Recently, Beaulieu has expanded her area of study to non-European art of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

____________________

Footnotes

[1] Elena Isabel E. de Gerlero, “Mass of Saint Gregory,” in Painting a New World: Mexican Art and Life, 1521–1821, eds. Donna Pierce, Rogelio Ruiz Gomar, and Clara Bargellini (Denver, CO: Frederick and Jan Mayer Center for Pre-Columbian and Spanish Colonial Art, Denver Art Museum, 2004), 96.

[2] A selection of authors involved in the discussion of Mass of Saint Gregory: de Gerlero, “Mass of Saint Gregory,” 95–102; Alessandra Russo, “Recomposing the Image. Presents and Absents in the Mass of Saint Gregory, Mexico-Tenochtitlan, 1539,” in Synergies in Visual Culture: Bildkulturen im Dialog, eds. Manuela De Giorgi, Annette Hoffmann, and Nicola Suthor, (Munich: Wilhelm Fink, 2013), 465–81; Gerhard Wolf, “Incarnation of Light: Picturing Feathers in Europe/Mexico, ca. 1400–1600,” in Images Take Flight: Feather Art in Mexico and Europe (1400–1700), eds. Alessandra Russo, Gerhard Wolf, and Diana Fane (Munich: Hirmer, 2015), 78–86; Eduardo de Jesús Douglas, “Indigenous Painting in New Spain, circa 1521–1600: Icon-Script, Manuscripts, Feather Paintings, and Murals,” in Painting in Latin America, 1550–1820: From Conquest to Independence, eds. Luisa Elena Alcalá and Jonathan Brown (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014), 71–101.

[3] Russo, “Recomposing the Image,” 465–81; Wolf, “Incarnation of Light,” 78–86.

[4] Ibid.

[5] For this interpretation see Douglas, “Indigenous Painting in New Spain,” 71–101; Russo, “Recomposing the Image,” 465–81. For a general discussion of art in colonial Mexico and the issue of cultural hybridity see Tom Cummins, “The Madonna and the Horse. Becoming Colonial in New Spain and Peru,” in Native Artists and Patrons in Colonial Latin America, eds. Emily Good Umberger and Tom Cummins (Tempe, AZ: Arizona State University, 1995), 52–83; Serge Gruzinski, Images at War: Mexico From Columbus to Blade Runner (1492–2019) (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001). For important discussions on cultural hybridity in the context of colonial Mexico more generally see Serge Gruzinski, The Mestizo Mind: The Intellectual Dynamics of Colonization and Globalization, trans. Deke Dusinberre (New York: Routledge, 2012); David Lockhart, “Double Mistaken Identity: Some Nahua Concepts in Postconquest Guise (1985, 1993)” in Of Things of the Indies (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1999), 98–119.

[6] The print on which the work is based is noted in Claire Farago, “Mass of Saint Gregory,” in Painting a New World: Mexican Art and Life, 1521–1821, eds. Donna Pierce, Rogelio Ruiz Gomar, and Clara Bargellini (Denver, CO: Frederick and Jan Mayer Center for Pre-Columbian and Spanish Colonial Art, Denver Art Museum, 2004), 100–1.

[7] Farago, “Mass of Saint Gregory,” 100.

[8] Douglas, “Indigenous Painting in New Spain,” 79.

[9] Farago, “Mass of Saint Gregory,” 100.

[10] Douglas, “Indigenous Painting in New Spain,” 78.

[11] Russo, “Recomposing the Image,” 467.

[12] Ibid.

[13] For a description of the goddess Tlaltecuhtli in Nahua art see H.B. Nicholson and Eloise Quiñones Keber, Art of Aztec Mexico: Treasures of Tenochtitlan (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1983), 61.

[14] Michel Graulich, “Aztec Human Sacrifice as Expiation,” History of Religions 39, no. 4 (May 2000): 352–71. For more scholarship on the Nahua religion and its belief in ritual sacrifice, see Jacques Soustelle, La pensée cosmologique des anciens Mexicains (Paris: Hermann, 1940); Christian Duverger, La fleur létale: Economie du sacrifice aztèque (Paris: Seuil, 1979); Yólotl Gónzalez Torres, El sacrificio humano entro los mexicas (Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica and Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 1985); Kay Almere Read, Time and Sacrifice in the Aztec Cosmos (Bloomington and Indianapolis, ID: Indiana University Press, 1998); Inga Clendinnen, Aztecs: An Interpretation (Cambridge, UK, and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991).