Paved Paradise: The Concrete and the Stuplime at Parc des Butte-Chaumont

by Madeline Porsella

“The modernization process is complete, and nature is gone for good.”

– Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1991)

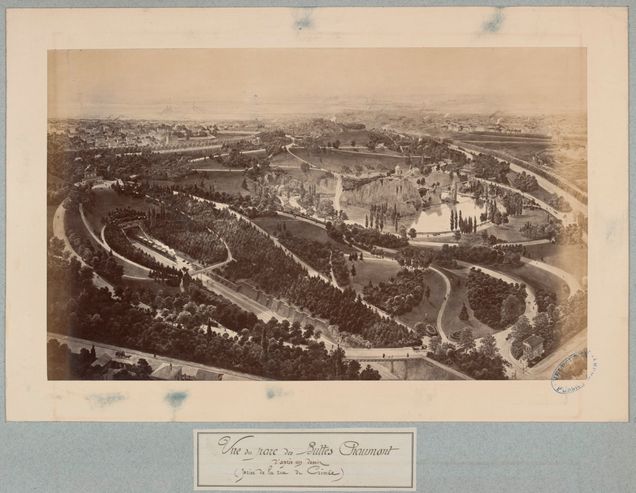

When the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont (Buttes-Chaumont Park) opened in conjunction with the Exposition Universelle on April 1, 1867, the city of Paris was in the midst of a legendary makeover undertaken in 1853 by Napoleon III, leader of the French Second Empire (1851–1870), and headed by Georges-Eugene Haussmann (1809–1891), prefect of the Seine. Medieval Paris’s narrow, winding streets, deemed unhealthy and unhygienic by nineteenth-century standards, were razed and replaced by wide boulevards, green spaces, and fountains. These changes, known as Haussmannization, created a new culture of display in Parisian public life, a “spectacularization” that reconfigured the relationship between citizens and the urban landscape. A rapidly developing technology, concrete, helped remake the city at every level beginning with the sewers that allowed wastewater to flow unseen under city streets. Haussmann and Jean-Charles Adolphe Alphand (1817–1891), who designed the Parc des Buttes Chaumont, used the site to experiment with concrete’s aesthetic possibilities. Decimating the existing landscape, they transformed an old refuse dump into a green space punctuated with picturesque vignettes (fig.1). Concrete allowed them to simultaneously subordinate and reproduce the environment, creating an artificial landscape that Ulf Strohmayer has called a “second nature.”1 The park’s overall effect was a simulacrum of nature “made naturally wild,” a controlled experience of pristine nature achieved via a total artificiality.2

Today, we live with the legacy of the resulting shift in our relationship to the landscape: romantic awe at nature’s unfathomable scale, the Kantian sublime, gave way to the fantasy of human domination, remaking the natural world as a containable and reproducible cultural product. Updating the sublime for the twenty-first century, Sianne Ngai coined the term stuplimity: the sublime meets tedium and repetition to the point of boredom and stupefaction.3 Nature writer Robert Macfarlane uses the term to describe the daily barrage of information regarding climate change, “the aesthetic experience in which astonishment is united with boredom, such that we overload on anxiety to the point of outrage-outage.”4 Due in large part to concrete fantasy-scapes in the legacy of the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont, we are confronted daily with statistics on humanity’s detrimental impact on the environment.5 Calamitous destruction is reduced to a data set.

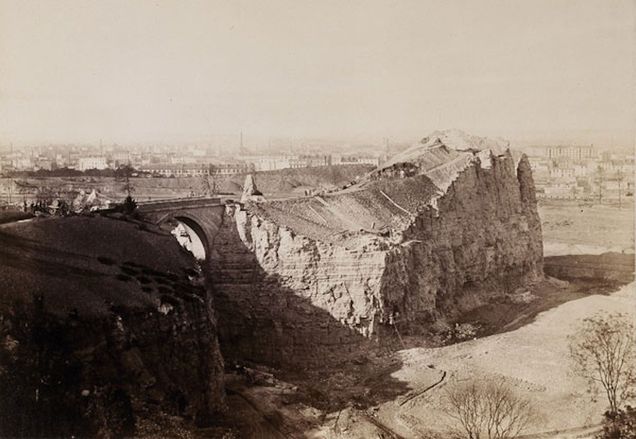

The Parc des Buttes-Chaumont was a new kind of spectacularized public works project. Breaking from the conventions of previous world’s fairs and exhibitions, installations at the 1867 Exposition Universelle were not limited to the Palais de l’Exposition; they bled out into the streets, putting renovated Paris on display.6 The concurrent debut of the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont demonstrates how sprawling the exhibition truly was. Named for the bleak topography that had previously occupied the site, Chauve-mont or bald hill, the park had an equally bleak history: for nearly 600 years it had housed the gallows where the French king not only hung criminals, but left them on display as a warning to any would-be delinquents. After the 1789 Revolution, it was used as a quarry and refuse dump (fig. 2). The seedy location was likely chosen for the contrast it provided with Alphand’s romantic vision, demonstrating the state’s modernity and power by paving over the site’s undesirable past.7 To any of the fair’s eleven million visitors, the awe-inspiring views and romantic features were only enhanced by knowledge of the gory wasteland that had preceded them.8

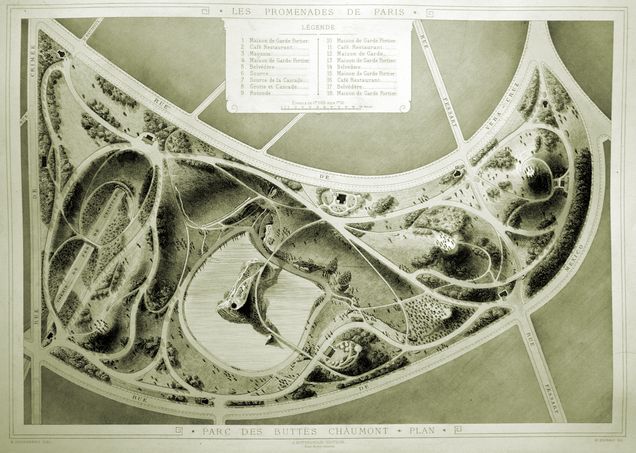

Ironically, the romantic natural feeling of the park was created with innovative artifice. Alphand envisioned a wild landscape punctuated with moments of the “engineered picturesque.”9 In order to evoke untouched nature, engineers employed technologies that eradicated the existing environment: concrete, landscaping, and water pumps. While Alphand’s functional concrete constructions, such as an artificial lake bed, were invisible to visitors, he also deployed the material as a surface treatment for innovative decorative features—cast faux bois (imitation wood) fences, rock faces, and stalactites were all made using concrete.10 Carefully designed vistas were visible from the elliptical paved paths snaking through the park (figs. 3 and 4).

In one striking example, Alphand transformed a pre-existing lacuna in the granite, a result of quarrying, into a grotto complete with faux stalagmites and stalactites and a cascading waterfall (fig. 5). A space that had previously been nothing but cut stone now presented itself as a natural marvel. Ulf Strohmayer argues that this reconciliation of technology and landscape is “not so much an act of concealment but of acceleration….”11 In the period eye, the park’s design, a “landscape full of simulacra…modeled on repetitions,” was a triumph of humankind’s capabilities.12 To be able to reproduce the grandeur of the natural world was to play god. This power was put on full display in the park, creating a spectacle of technology and labor, the twin engines of modernization, masquerading as untouched nature. Concrete is not disguised; “it is resolved… into its products—which can thus celebrate both nature and human ingenuity.”13 A new landscape was formed, one that recast nature and culture as oppositional forces while demonstrating that, in truth, they produce one another.

The Parc des Buttes-Chaumont anticipates the end-product of this accelerating cycle of growth and modernization—modern, and even postmodern, Paris. Peter Collins, author of Concrete (1959), locates a shift from aristocratic favor for carving and masonry to a taste for democratic modes of building—casting and molding—in the late eighteenth century.14 Broadly, this reflects the changing values of the time, an acceleration towards a mass-consumer society. The widespread adoption and use of concrete aligned with a shifting social structure fomented by urban environments; cities industrialized, grew, and modernized to meet demand as people flooded in to provide labor. These new denizens became consumers of the goods produced under industrial conditions. By the mid-nineteenth century, concrete technology was ready to rise to society’s needs, supporting the new infrastructure of both mass production and mass consumption.

In the intervening century and a half, we have poured concrete at a monstrous pace. Concrete continues to lay the foundations for high-rises, highways, suburbs, subways, and urban sprawl, the infrastructure of modern life. It is second only to water in rankings of the world’s most used building materials.15 Due to a carbon-intensive production process, concrete is responsible for about eight percent of global carbon emissions.16 China is by far its largest consumer on earth, releasing 858.23 million tons of CO2 in 2020.17 This is largely the result of amped-up development projects designed to demonstrate state authority by dominating nature. In this way, China builds upon the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont’s legacy.

The Three Gorges Dam, one such infrastructure project, exemplifies how concrete use has developed globally from the nineteenth century to the present day (fig. 6). The concrete hydroelectric gravity dam in Hubei Province was ironically conceived in an effort to limit greenhouse gas emissions from coal. It has had an immeasurable impact on the surrounding environment—increasing risk of landslides, accelerating extinction of indigenous wildlife, displacing over a million Chinese residents, and flooding archaeological sites that once sat on the river’s banks. It is so massive that its weight is estimated to have increased the length of earth’s day by .06 seconds.18

Archeologist Christopher Witmore uses the Three Gorges Dam, as imaged in Edward Burtynsky’s photographs, to describe the “Hypanthropos,” his neologism for our current epoch, defined by calamity and the often monstrous and unanticipated consequences of human projects.19 Witmore’s term is offered to replace the more commonly used “Anthropocene,” our current geological period defined by human impact on the stratigraphic record. In a 2018 paper on concrete and ice, anthropologists Tim Ingold and Cristián Simonetti identify concrete as “the most obvious candidate for marking the origin of the Anthropocene.”20 In their argument, concrete is the material that afforded humans enough power over the landscape to impact the geological record.

The term Hypanthropos is playfully constructed to remind us that, though the Anthropocene is marked by human activity, we are not in control. It is a double-entendre: the prefix hyp- recalls both the Greek prefix hyper-, meaning “excess, overwhelming being,” and hypo-, meaning “a sense of being under, beneath, [or] below something.” Humans, Witmore explains, are “suspended above and below”; they both overwhelm their environments and are contained within or overwhelmed by them.21 Hypanthropos’s multiple meanings displace the anthropos, the human, in their larger ecological context. The Parc des Buttes-Chaumont and the Three Gorges Dam are unique to the Anthropocene, human-made objects with massive environmental impacts. They reinvent nature “as contrast—with culture, with symmetry,” when, in reality, no such opposition exists.22 Nature is paradoxically both produced by and a container of culture, both hypo and hyper, above and below.

Witmore uses Burtynsky’s images of the colossal concrete dam as a medium for illustrating our suspension. If the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont modeled concrete’s usefulness in creating controlled landscapes, then contemporary concrete infrastructure projects, which have caused immeasurable and unpredictable ecological destruction, show the fallacy in that promise. Witmore reminds us that though the scale and impact of the Three Gorges Dam are astonishing, “Over the last two decades more than half of the concrete ever produced was mixed, poured, and set—4.3 billion tons were produced in 2014 alone. As for ‘water control and utilization’ projects, more than one large dam has been built every year for at least the last 60.”23 This is the legacy of Alphand’s experiments in concrete.

When the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont opened, it solidified the illusion that culture could dominate and tame nature, turning it into a reproducible commodity. Concrete was the critical technology in establishing the park’s “second nature,” an environment of artificiality.24 However, our current state of climate catastrophe has proved that illusion, or rather delusion, to be dangerously false. No matter how convincingly we cast imitation stalactites, they will never be more than cheap reproductions. Projects like the Three Gorges Dam remind us that our technological know-how does not elevate us above the natural world. No amount of concrete will remove us from the planet’s delicate ecosystem.

____________________

Madeline Porsella is an interdisciplinary historian and artist based in New York, NY. She studied studio art at Bard College and is currently pursuing her MA in Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture at the Bard Graduate Center. Her research is focused on the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries where her areas of interest include the incorporation of new technologies into art and design, new media, the relationship between science and the occult, and cultural constructions ranging from memory to the gendered body.

____________________

Footnotes

1. Ulf Strohmayer, “Urban Design and Civic Spaces: Nature at the Parc Des Buttes-Chaumont in Paris,” Cultural Geographies 13, no. 4 (October 2006): 570.

2. Strohmayer, “Urban Design and Civic Spaces,” 565.

3. Sianne Ngai, “Stuplimity: Shock and Boredom in Twentieth-Century Aesthetics,” Postmodern Culture 10, no. 2 (2000). doi:10.1353/pmc.2000.0013.

4. Robert Macfarlane, “Generation Anthropocene: How humans have altered the planet forever,” The Guardian, April 1, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/apr/01/generation-anthropocene-altered-planet-for-ever.

5. Christopher Witmore, “Hypanthropos: On Apprehending and Approaching That Which Is in Excess of Monstrosity, With Special Consideration Given to the Photography of Edward Burtynsky,” Journal of Contemporary Archaeology 6, no. 1 (2019): 144.

6. Anne O’Neil-Henry, “Introduction,” Dix-Neuf 24, no. 2–3 (2020): 115–122.

7. Abigail Susik, “Aragon’s ‘Le Paysan de Paris’ and the Buried History of Buttes-Chaumont Park,” Thresholds, no. 36 (2009): 68.

8. Ann E. Komara, “Measure and Map: Alphand’s Contours of Construction at the Parc des Buttes Chaumont, Paris 1867,” Landscape Journal 28, no. 1 (2009): 35–36.

9. Ann E. Komara, “Concrete and the Engineered Picturesque the Parc des Buttes Chaumont (Paris, 1867),” Journal of Architectural Education 58, no. 1 (2004): 5.

10. Komara, “Concrete and the Engineered Picturesque,” 6–9.

11. Strohmayer, “Urban Design and Civic Spaces,” 565.

12. Strohmayer, “Urban Design and Civic Spaces,” 569.

13. Strohmeyer, “Urban Design and Civic Spaces,” 566.

14. Peter Collins, Concrete: The Vision of a New Architecture: A Study of Auguste Perret and His Precursors (New York: Horizon Press, 1959), 19.

15. Man-Shi Low, “Material Flow Analysis of Concrete in the United States,” (MS thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2005), 11.

16. Justin Davidson, “Concrete Doesn’t Have to Be an Ecological Nightmare,” New York Magazine, December 3, 2021.

17. Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser, “CO₂ and Greenhouse Gas Emissions,” OurWorldInData.org, accessed December 17, 2021.

18. Witmore, “Hypanthropos,” 139.

19. Witmore, “Hypanthropos,” 143.

20. Simonetti Cristián and Tim Ingold, “Ice and concrete: solid fluids of environmental change,” Journal of Contemporary Archaeology 5, no. 1 (2018): 27.

21. Witmore, “Hypanthropos,” 143.

22. Strohmeyer, “Urban Design and Civic Spaces,” 565.

23. Witmore, “Hypanthropos,” 139.

24. Strohmeyer, “Urban Design and Civic Spaces,” 570.