Cut With the Tailor Scissors: Hannah Höch’s Textile Designs and the Development of Photomontage

by Iris Giannakopoulou

Hannah Höch (1889–1978) is best known for her participation in the Berlin Dada movement and her pioneering works of photomontage, collages made mostly or entirely from photographic reproductions. Her piece Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany, exhibited in the First International Dada Fair at the Otto Burchard Gallery in Berlin in 1920, stands as one of the most iconic images of this European avant-garde movement (fig. 1). Emphasizing her diverse background in handicrafts and the applied arts and her unique position as the only female member of the group, this essay demonstrates the influence of textile design on Höch’s photomontage practice. In doing so, it challenges prevailing modernist narratives of the late 1910s and early 1920s surrounding the development of the medium in association with male artists and with disruptive and virile connotations.

During the mid-1960s, American art critic and curator William Rubin called the development of photomontage “the most significant contribution” of the Berlin Dada and ascribed its invention to the group’s founding member Raul Haussman.1 The artist, however, was not “the first Berliner to hit upon the photomontage” as Rubin contended, or at least not the only Berliner.2 In fact, both Haussman and Höch, a couple at the time, discovered the powerful potential of photomontage during a summer trip to the island of Usedom in the Baltic Sea in 1918. There, the two came across a popular type of engraving at local homes and businesses, which involved collaging photographic portrait heads of local men who were away at war onto found torsos. These mementos had a distinct visual impact on the two artists who were already familiar with the photocollage posters of fellow Berlin Dada members John Heartfield and George Grosz.3 Since 1916, Heartfield and Grosz had been experimenting with collages made from photographic reproductions. Their works, however, were primarily geared towards creating provocative political statements and lacked the artistic qualities of these popular pictures. Upon their return to Berlin, Haussman and Höch began experimenting with the medium by clipping photographs from a variety of illustrated sources and mixing them to create new visual imagery that, as Haussman would later recall, “attacked the political events of the day with biting sarcasm.”4

Höch was especially well-equipped when it came to harnessing the potential of the emerging medium. Unlike Haussman, who was formally trained in sculpture and painting, Höch came from the world of crafts. Before the war, she studied glass design and calligraphy at the Charlottenburg School of Applied Arts in Berlin, while in 1915 she transferred to the graphic and book arts program of the State Museum of Applied Arts. During her training, Höch begun to focus on embroidery, a craft that, as a woman, she had likely cultivated from a young age; she earned recognition for at least two designs that were subsequently featured in the Darmstadt needlework journal Stickerei- und Spitzen-Rundschau (Embroidery and Lace Review). With her training in graphic design and experience with embroidery, Höch secured a part-time position at Ullstein Verlag, one of Germany’s largest interwar-era publishing houses.5 Between 1916 and 1926, Höch worked three days a week at the pattern division of Ullstein (fig. 2). In this position, she was responsible for designing patterns for knitting, crocheting, and embroidering, and she created advertising vignettes and typographic layouts for magazines such as Die Dame (The Lady) and Die Praktische Berlinerin (The Practical Berlin Woman) (fig. 3). Höch’s responsibilities extended beyond design: she also oversaw the fabrication of these patterns, utilizing a range of techniques including cutwork, drawn- and pulled-threadwork, needle-lace, darned-filet, and embroidery.

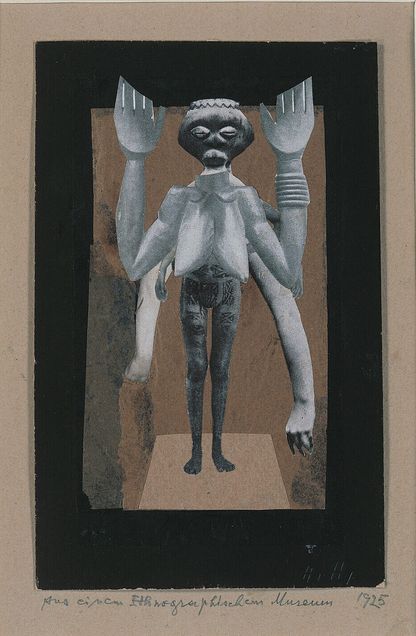

This diverse background equipped Höch with a wide range of technical and artistic skills that she was able to apply when creating her photomontages. Her experience in book and graphic design honed her ability to organize visual elements, text, and images into cohesive compositions within a limited space, effectively conveying visual messages. For instance, in Cut with the Kitchen Knife, the deliberate placement of a map depicting European countries that granted women voting rights at the bottom-right corner of the piece—the location usually reserved for the artist’s signature—subverts layout conventions, delivering a clear political statement about women’s empowerment. At the same time, Höch’s special attention to detail and careful consideration of color and texture can be attributed to her experience with embroidery, while the particular emphasis she puts on the outlines of her ‘cutout’ silhouettes is reminiscent of the figures in textile pattern designs as vividly seen in her 1925 piece Sadness (fig. 4). In this photomontage, a hybrid black and white figure occupies the center of the composition, which otherwise consists of an abstract background and a black border. Here, Höch assembles an intricate female figure that invokes some sort of deity and presents it to us on a pedestal, as if on display.

Höch’s photomontages owe greatly to her work with handicraft and textile design and her involvement in the commercial and publishing world of Ullstein, which constitutes part of the technical, material, and formal ecology of her artistic work. As a designer at Ullstein, Höch enjoyed easy access to a wealth of resources, including multiple copies of sewing and handiwork patterns produced by the company, as well as a vast array of illustrated magazines and other printed material. She incorporated these materials, along with recycled textile items, printed papers, and photographic reproductions sourced from various magazines—that she meticulously organized in scrapbooks—in her first attempts with collage and photomontage from as early as 1919. For instance, needle-lace patterns appear in her 1919 collage White Form while diagrams of filet, a kind of net (or grid) into which a design is darned, serve as a background in Tailor’s Flower (1920), as well as her 1921 piece, On a Tulle Net Ground (fig. 5). Many of the media sources that Höch uses in her photomontages come from Ullstein publications such as BIZ and Die Dame. This is especially evident in her use of BIZ material in her Dada pieces Cut with the Kitchen Knife Heads of State (1918-1920), or Dada Panorama (1919) (see fig. 1).

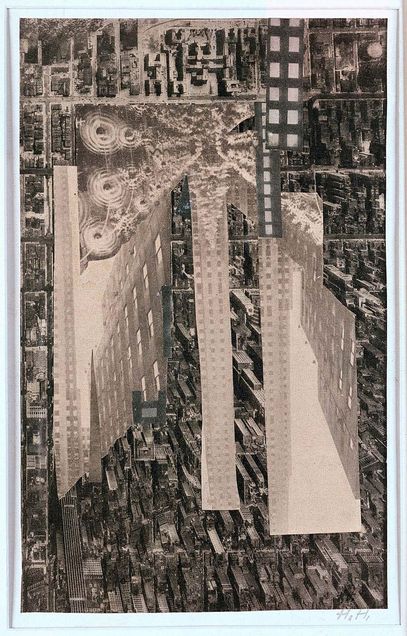

The interrelation between Höch’s textile designs and her photomontage work extends beyond their technical and material analogies, making her work explicitly different from that of her male colleagues. Referencing Kay Klein Kallos’s 1994 dissertation on the relationship between design and the avant-garde in the work of Hannah Höch, art historian Maria Makela draws attention to the formal affinity between “Höch’s diagrams for darned filet and needle lace” and “the compositional structure of her neatly formatted collages and photomontages, which are basically two-dimensional and usually arranged on a vertical-horizontal grid” (fig. 6).6 To this analysis, one can add other matters of artistic form that are associated with textile design, such as the dynamic interplay of positive and negative forms, as well as the intricate relationship between background and foreground that characterize her photomontages (fig. 7). Admittedly, Höch’s work is more “surface-oriented,” more “strongly patterned,” and more “rigorously structured” than that of her male Dada colleagues, who took a more a violent, destructive, and chaotic approach to their photomontages and whose assemblages exude a sense of agitation and anti-coherence.7 The profound importance of textiles for Höch surfaces prominently in My House-Sayings, a farewell piece she made in 1922, following her separation from Haussman and withdrawal from Dada. Inspired by the German tradition of guestbooks in which visitors could leave wishes and sayings upon departing from one’s house, this complex and multilayered photomontage combines in a constructivist grid, various Dada emblems and sayings by Dadaists and other like-minded writers, along with carefully selected clips of photographs—including her own—and several pieces of textile designs that Höch places at the center of the composition.

While at Ullstein, Höch made a design for the cover of one of its pattern publications. Her sketch depicts the figure of a little girl with a bow on her hair holding a relatively enormous pair of tailor scissors. The girl sits atop of a sphere, which the faded longitude and latitude pencil-lines suggest is not a ball of yarn, but the globe. Its surface is layered with patterns of clothing “which appear like continents waiting to be sewn together,” as Max Boersma explains, while “the word listed beside them—einreihen [to line up]—carries textile, orderly, and militaristic associations.”8 In his interpretation, the sketch “can suggest the gathering of fabric along a line during the process of stitching, as well as the act of getting in line or joining ranks.”9 However, juxtaposed with the Communist emblem of the hammer and sickle, her sketch evokes another layer of meaning. In a manner analogous to the aspirations of communist proletarian solidarity among peasants and workers seeking to change the world, Höch’s symbol is suggestive of a constructive unity between the spheres of art and crafts as a means of changing the world. For Höch’s part, it seems like there was no contradiction between these two worlds. Such reading, however, disturbs the carefully crafted anti-art, anti-establishment, and anti-aesthetic myth of the Dada revolt. “From the outset, Höch’s photomontage aesthetic was deeply rooted in design traditions, and it was perhaps this as much as anything that led many to discount her work,” insists Makela, even the Dadaists themselves.10 The distinct and multifaceted nature of her artistic output make Höch resistant to easy labels and categorizations, but it might be precisely this radical resistance that makes Hannah Höch even more quintessentially ‘Dada.’

Höch’s ‘cutting with the tailor scissors’ begets a re-evaluation of the historiographic ‘cuts’ historians perform within their own historical montages. In his seminal theory of the avant-garde, Peter Bürger defines the historical emergence of the avant-garde movements in the early twentieth century as a break in the history of art and a violent rupture with the Institution Art, or the framework within which an artwork is produced and received.11 The narrative of Dada’s dismantling of “the cult of art” and the tradition of newness associated with it, as provocative and alluring as it is, curtails our understanding of the complexity and variety of responses that artists gave to the rise of modern industrial capitalism and eschew the multifaceted and often ambivalent ways in which the avant-garde movements participated in ‘the modern life.’ Weaving a genealogy that links the development of photomontage medium to the domestic arts and clothing reform, to style and fashion, to popular magazines and mass-advertisement, and beyond, to women’s pastimes and feminist activism, Höch’s artistic work offers valuable and nuanced insights into these issues. “Preferring to accept the evidence of hand cutting over the creation of seamless illusion,” Höch and her tailor scissors invite a closer look into the stitches, the threads, and the critical scraps that are often cut out in our historical montages.12

____________________

Iris Giannakopoulou is a PhD candidate in the History and Theory of Architecture at Yale University where she studies the relationship between architecture and politics in the postwar period. Her dissertation examines how the censorious climate of the early Cold War years impacted the practice, discourse, and overall culture of architecture in the United States. Her previous academic work involves spatial histories of radicalism in modern architectural design and urban planning practices, as well as the historical avant-garde movements’ significance in shaping individual and collective political possibilities. She holds a Diploma of Architecture from the National Technical University of Athens, Greece (2014) where she is a licensed architect, and a Master of Science Degree in Architecture Design as a Fulbright Scholar from the MIT School of Architecture (2018).

____________________

1. William Rubin, Dada, Surrealism and their Heritage (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1968), 42.

2. Rubin, Dada, Surrealism and their Heritage, 42.

3. Maria Makela, “By Design: The early work of Hannah Höch in context,” in The Photomontages of Hannah Höch, ed. Peter Boswell, Maria Makela, Carolyn Lanchner (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 1996), 59. In her essay “A few words on photomontage,” Höch refers to the “first instances of this form, i.e. the cutting and rejoining of photos or parts of photos,” which, among others, may be found “in the fading, curious pictures representing this or that great-uncle as a military uniform with a pasted-on head. In those days the head of a person was simply glued onto a pre-printed musketeer.” Höch, “Několik poznámek o fotomontáži,” Stredisko 4, no. 1. (April 1934), unpaginated; translated by Jitka Salaguarda as “A Few Words on Photomontage” and reprinted in Maud Lavin, Cut with the Kitchen Knife: The Weimar Photomontages of Hannah Höch (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 219–20.

4. Raoul Hausmann, “Photomontage,” in Photography in the Modern Era: European Documents and Critical Writings, 1913–1940, ed. Christopher Phillips, trans. Joel Agee (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Aperture, 1989), 178.

5. Ullstein Verlag’s portfolio included mass-circulation periodicals such as the Berliner Morgenpost (Berlin Morning Post), BZ am Mittag (Berlin Newspaper at Noon), the weekly Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung (Berlin Illustrated Newspaper), the liberal newspaper Vossische Zeitung, and a number of smaller circulation magazines.

6. Makela, “By Design,” 62. Also see, Kay Klein Kallos, “A Woman’s Revolution: The Relationship between Design and the Avant-Garde in the Work of Hannah Höch 1912-1922,” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Wisconsin, Madison, 1994).

7. Makela, 62.

8. Max Boersma, “Global Patterns: Hannah Höch, Interwar Abstraction, and the Weimar Inflation Crisis,” Grey Room, no 91 (Spring 2023): 18.

9. Boersma, “Global Patterns,” 18.

10. Makela, “By Design,” 62. John Heartfield and George Grosz are said to have opposed her inclusion in the First International Dada Fair of 1920 and succumbed only after Raoul Hausmann threatened to withdraw his own work from the exhibition. Furthermore, in their memoirs, Höch mentioned her only in passing or omitted reference altogether. See, Richard Hülsenbeck, Memoirs of a Dada Drummer (1969), ed. Hans J. Kleinschmidt, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991); George Grosz, George Grosz: An Autobiography, trans. Nora Hodges (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997).

11. Peter Bürger, Theory of the Avant-Garde, trans. Michael Shaw (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984).

12. Peter Boswell, et al., The photomontages of Hannah Höch, 2.