Re-Fuse: The Macro-Ecologies of Microfiber Waste

by Adelaide Theriault

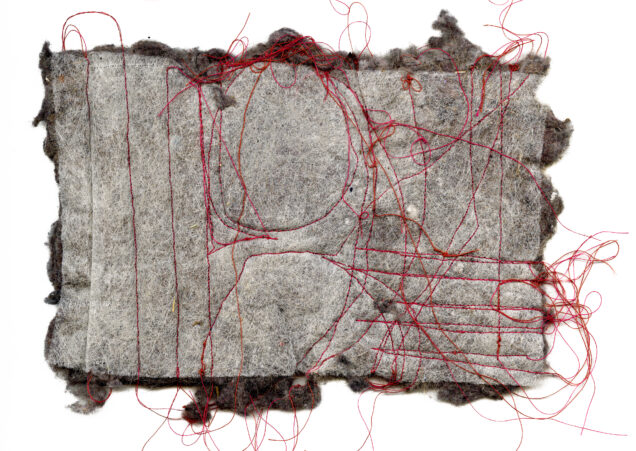

Figures 1-7. Adelaide Theriault. Sediment and Erosion (1-7) (2023). Digital scan of laundry lint, hair, skin, dust, microplastics, natural fibers, cotton thread, dryer sheets, various other debris from laundered fibers. 34 x 24 in. each (86.4 x 61 cm). Images courtesy of the artist.

I think often of dust, of erosion, and of the ever-changing contents in contemporary soil bodies. The fabricated separation between humans and their co-inhabitants is a tool for the upkeep of capitalist extraction that shelters us from the vibrant reality of our ecological presence—a presence that exists regardless of our intentions and, frequently, in spite of our perceptual limitations. I am reminded of this human presence and of my own roles within my ecological webs when I witness squirrels building homes within the engine of my father’s broken-down work truck, or when I see birds nesting in hollow shop sign letters. I see the active role that I play in the grasses whose seeds disperse by clinging to and falling from my clothes. I am interested in the ecological, social, and geological significance of matter such as laundry lint, concrete, and grasses—and I believe that any and all forms of matter can act in their place as a lens for eco-critical research.

Laundry lint documents and communicates the social and ecological memory held within its fibers. The layers of lint that build up inside the dryer screens at my local laundromats are reminiscent of the geological diagrams of my childhood textbooks, in which the layers of soil and rock are visually isolated, acting as timestamps. As I collect the lint from loved ones and laundromats, I learn about the habits and lives of the people I share space with, through the debris of forgotten receipts and felted sheets of their pets’ hair. I think of laundry lint as a soil itself—not only visually, but through its physical makeup and its relationships to greater ecological webs. Laundry lint is a tangible artifact of contemporary textile culture and of the slow erosion of matter. The laundering and manufacturing of synthetic textiles, along with the conception, recycling, and discharging of wastewater, creates conditions for the movement of microplastics across Earth’s surface. As these microplastics accumulate in soils, they entangle deeply into new ecological webs, enacting gradual change within the bodies of the plants, humans, and non-human animals that consume them.

In recognition of these webs, and of the deep-time cyclical lives of microfibers—from microplastics to animal fibers to cotton—I embroider collected lint on dryer-sheet backings. These topographical maps created from lint and thread draw inspiration from the familiar imagery of urban and agricultural grids I have seen from airplanes and on satellite maps. On the reverse side, however, the threads that bind the matter together become tangled, pouring out off the edges of their photographic containers, as can be seen in Sediment and Erosion (Composition #8 of 8) (fig. 8). I am interested in calling attention to the subsurface of the ground, of memory, and of our perception. These threads point to the entangling interspecies relationships of subterranean life—fungal, animal, microbial, electrical, and botanical. These relationships are now in collision with anthropogenic conduits for the transport of water, information, power, and oil along with their resulting fields of debris. I am driven and creatively stimulated by the reorientation that occurs in me in order to understand my relationship to the subsurface, because it requires me to deprioritize visual ways of knowing the world. This way of thinking about plastic pollution occupies a long-term, non-linear timeline. I felt moved and torn by the recognition that this tiny plastic material—one with origins deep beneath Earth’s surface where it was extracted as fossil fuels—could be submerged once again in the soil, yet be so unable to break back down and return home.

Figure 8. Adelaide Theriault. Sediment and Erosion (8) (2023). Digital scan of laundry lint, hair, skin, dust, microplastics, natural fibers, cotton thread, dryer sheets, various other debris from laundered fibers. 34 x 24 in. ( 86.4 x 61 cm). Image courtesy of the artist.

Plant communities, too, have networks of conduits for the transport of nutrients, water, and information that are being increasingly intersected by microplastics. Some plants’ roots can be inhibited from absorbing all that they need by plastics. Other plants may absorb dyes and plastic-derived toxins, transporting them through their roots and stems to their leaves and fruits. Plants bear much of the current brunt of microplastic dispersal, but they are not simply passive victims or witnesses to this pollution. The pollution-induced stress that many plants face is a result of their capacity to enact physical, chemical, and restorative change. Plants are often used in constructed wetlands to clean sewage and wastewater because of their key role in the ecosystems that host beneficial algae and micro-organic decomposers. Our familiar desert and prairie grasses, too, play restorative roles by holding and securing bodies of soil, preventing particulate erosion and dispersal.

In response to my understanding of these plant and pollutant relationships in contemporary soils, I planted grass seeds local to Albuquerque’s high-desert ecosystems in beds of laundry lint. The lint held water and provided nutrients for the grass in the form of the dead skin cells, decaying natural fibers, and hair amidst the synthetic matter. The grass, in exchange, grew to hold the lint securely in its roots, protecting it from erosion.

The grasses lived only for a short season before I left them to dry, because I realized that what I was doing was asking them to sacrifice themselves to plastic toxicity in order to hold this symbol of repair. Images 1 and 2, in the series From Old Growth, commemorate the relationship between the grasses and lint, presenting a feeling of hope, repair, and regrowth from refuse (figs. 9 and 10). They also serve as a symbol of mourning for the irreversibility of the pollutant ripples that unfurl from the extractive systems that define the Capitalocene, an alternative designation for the current epoch that emphasizes capitalism’s central role in driving environmental degradation and societal inequalities.

Figures 9-10. Adelaide Theriault. From Old Growth (1 and 2 of 7) (2022). Digital scan of laundry lint, water, sunlight, native grasses. 36 x 24 in. each (91.4 x 61 cm). Images courtesy of the artist.

This moment within my larger creative research practice presented to me a reminder of the necessity of a shift away from a strictly anthropocentric worldview—one that reduces non-human matter to passive roles. When we refuse this authoritative, extractive perspective in exchange for one that recognizes the place-making, sensing, and restorative capacity of all parts of this more-than-human world, we have an opportunity to re-fuse severed ecological relationships.

____________________

Adelaide Theriault is a trans-disciplinary artist currently based on Tiwa lands in so-called Albuquerque, New Mexico, where they are working towards an MFA in Sculpture and Art and Ecology at the University of New Mexico. Adelaide works sculpturally, photographically, and performatively with found materials and site-specific sensory inquiry to nurture a practice of ecological research. Adelaide has shown in exhibitions across New Mexico and Texas, and was most recently nominated as a 2022-2023 SITE Scholar at SITE Santa Fe.

____________________