Dangers of Response: “I modi” and its Censorship

by Iakoiehwahtha Patton

Erotic imagery comprised a significant portion of artistic production in Renaissance Italy. It is within this cultural context that the reclining nude became an archetype and a contested site where censorship could be enacted. The nude was particularly criticized for its sinfulness, so much that in the late fifteenth century, the Dominican Friar, Girolamo Savonarola, fervently preached against artists who painted “figures with bare breasts.”1 With the rise of the Protestant Reformation, these objections to the naked body only increased by the turn of the sixteenth century.2 It is not surprising, then, that most erotic images disappeared over the course of the sixteenth century, despite the importance of the erotic within Renaissance visual culture.3 This relationship between art and censorship brings our attention to Giulio Romano’s I modi (c. 1520s), which represents the most controversial erotic visual material to emerge in sixteenth-century Italy.

I modi saw wide-scale destruction to the extent that all that remains of the original sixteen images in the series are fragments, two engravings, and a woodcut. Our knowledge of the original drawings and print series primarily comes from the Italian author Pietro Aretino’s sixteenth-century sonnet book published in Venice (1526), decades after the original drawings.4 In Italian, the title I modi has many interpretations, but it has been consistently translated into English as The Positions.5 However translated, the title describes what the series entails: sixteen heterosexual couples engaging in sexual acts in varying positions. The title and the figures are presented under no mythological guise or allegory. Rather than using Classical mythological imagery that borrowed from antique paradigms, I modi divulges itself as unmistakably and primarily erotic. Previous art historical scholarship has acknowledged the inherent eroticism of I modi but has done so within the broader context of erotic images that pervaded Renaissance Italy by focusing on I modi’s origins.6 In this essay, I nuance previous analyses by highlighting I modi’s reception and viewer participation within the discourse of censorship. Through the series’ unmitigated imagery, I modi became a provocative assemblage, building upon an antique topos with blatant sexual subject matter that is enlivened through viewer engagement. Much like the genre of the nude image, I modi, consequently, became a contested site that provoked widespread censorship.

The story of I modi’s production and dissemination unfolds in multiple parts. In the 1520s, Giulio Romano inherited Raphael’s lucrative and prestigious workshop in Rome after his death.7 In this position, he established an advantageous relationship with Marcantonio Raimondi, a printmaker to whom Romano supplied drawings.8 In Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori, e architettori (1550), Vasari provides the fullest written source that concerns the creation and reception of I modi.9 Yet even with Vasari’s text, questions remain regarding the intention and patronage behind Romano’s original drawings.10 In Le vite, Vasari indicates that Romano made twenty drawings of heterosexual couples engaging in explicit sexual acts under no mythological veil. These drawings were then given to Raimondi, who made a set of engravings based on Romano’s drawings in 1524. Influential author and satirist Pietro Aretino then wrote salacious sonnets to be paired with each image, which were drafted into a book in 1526. It is at this point that Pope Clement VII became enraged, the prints were banned, and Raimondi was imprisoned.11 By the time the scandal occurred, Romano had accepted a position in Mantua at the court of Federico Gonzaga and, luckily for him, remained unscathed by the events in Rome.12

In reading Le vite, art historian Bette Talvacchia argues that Vasari’s intention was not to recall events accurately, but rather that Vasari intended to use the story of I modi as a warning against “outrage.”13 Vasari explicitly states that “the gifts of God should not be employed, as they very often are, in things wholly abominable, which are an outrage to the world.”14 Vasari was not only writing at a moment when the modern concept of the “artist as genius” was emerging, but was also an active creator of this myth. This condemnation is clear within its original context; in Le vite, Vasari constructs the biographies of famous Renaissance artists whilst defining boundaries for acceptable artistic behavior. Therefore, Vasari not only condoned I modi’s censorship, but actively participated in it by cementing the scandalous legacy.

Vasari’s text suggests that I modi’s replication and dissemination in print called for intervention. I modi was published during a historical moment in which erotic engravings as a genre were novel. In the late fifteenth century, erotic engravings were beginning to be produced for the art market, which allowed for wider accessibility and a new merchant-class clientele.15 Previously, erotic images were largely commissioned by and executed for the elite, whose social position guaranteed a controlled viewing context.16 This speaks to the strict boundary of what constituted fine art as opposed to what was seen as vulgar imitations of it. This boundary was dependent on which actors controlled erotic imagery and in this regard, the intended viewers were mostly men in elite circles with a level of humanist education. When removed from this controlled context, the images are free from constraints, allowing the observer to respond uninhibitedly.

In I modi’s printed reproductions, the series’ sexually explicit imagery is unmediated as it moves from the private elite sphere of individual drawings to the more public arena of circulated prints. In doing so, I modi transforms from a commissioned series of finished drawings by a renowned artist into scandalous, decontextualized reproductions by landing in the hands of what David Freedberg calls the “vulgas”; I modi became consumable by the masses.17 The already sexualized bodies are rendered objects charged with the ability to elicit natural, yet dangerous responses from the images’ viewers. In this respect, the body as a site for censorship serves as a mechanism of social and sexual control.

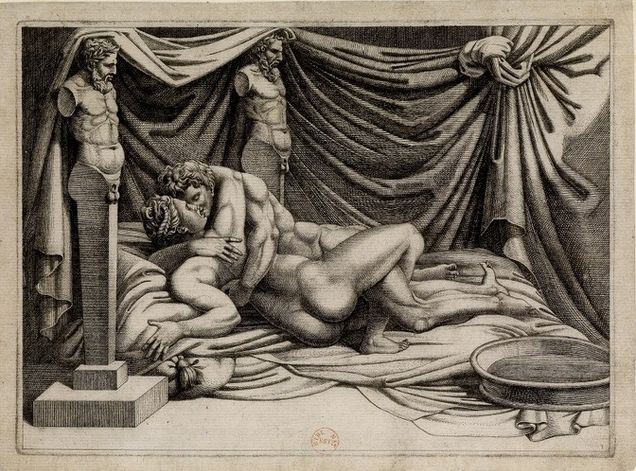

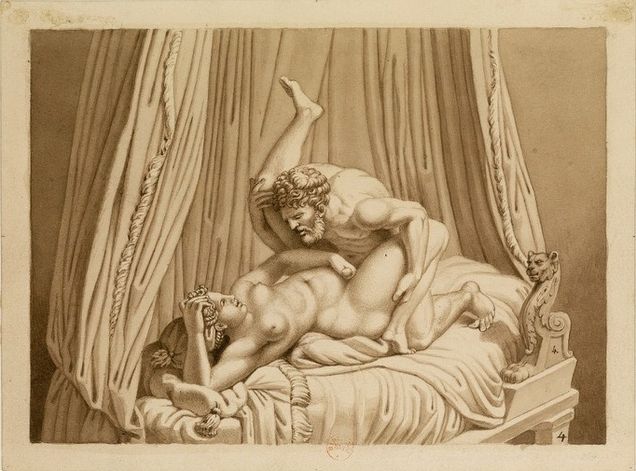

Though Romano’s originals no longer survive, copies in the form of prints and drawings have endured.18 Now housed at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BNF), the Paris Position is a nineteenth-century hand-drawn replica of Position 1, the first in the original series by Romano (figs. 1 and 2).19 The Paris Position was originally drawn and owned by French antiquarian, Jean-Frédéric Maximilien de Waldeck.20 Waldeck not only drew the Paris Position but illustrated twenty wash drawings of I modi (fig. 3).21 Now, both are kept together at the BNF with a preface by Waldeck. In a Vasarian manner, Waldeck provides a history of the I modi scandal and his interest in the series. The Paris Position portrays a heterosexual couple embracing on a bed of sheets. The woman lies on her side, displaying her back as she holds her lover with her right arm and grasps the sheets with her left. Her breasts, genitalia, and the penetrative act are hidden, which are features that do not seem incidental when considering the print’s survival. Rather than the sexual act itself, the formal emphasis is placed on the visual entanglement of limbs. Additionally, the woman recalls the docile, reclining nude popularized in sixteenth-century paintings, which provides a contrast to the active women in the other I modi prints (figs. 4-6).22 For a series that has only narrowly survived iconoclastic efforts, it is not by accident that the position with the least amount of sexual exhibitionism has survived in more than one example.

With sexual intercourse hidden, the observer of the Paris Position is prompted to fill in the blanks. The suggestion of penetration enhances its arousing aspect, thereby eliciting an imaginative engagement by the implied heterosexual male viewer. This type of viewer participation is even more explicit in I modi’s afterlife. The British Museum’s set of nine fragments has been reduced to torsos, heads, and limbs (fig. 7). Their treatment is decidedly violent. In their seemingly inoffensive states, the fragments only accentuate their erotic potential. Like the Paris Position, to engage with the fragments is to imagine their missing actions. Drawing upon Freedberg’s theory of viewer reception in The Power of Images, the “borderline” quality of the images is what elicits arousal.23 In this regard, the “borderline” of what art is drives its erotic potential; tension is what renders I modi illicit. Ultimately, it is the censorship of I modi which attempted to quell the sexual response that drove its eroticism. The series’ heightened intrigue is attested to by its survival as collected objects, even in fragmented form.

In the Paris Position, the couple is flanked by two herms, whose inclusion conveys the Renaissance adoption of a classical precedent and hints at a broader sexualized Ovidian allusion.24 The herms function not just as furnishings that support the drapery and frame the image, but they also act as witnesses to the sexual events unfolding before them. They are placeholders for the external viewers and function as second eyes through which the viewer engages with the sexual act. In this mirrored gaze, the intended heterosexual male viewer is implicated, allowing for a virtual, yet controlled, engagement with the couple as tangible figures. In applying Freedberg’s framework, the herms become enlivened participants in their voyeuristic attentiveness to the couple, thereby bringing attention to the relationship between looking, enlivening, and erotica that permeates the Paris Position.

Like sculpture, the affordance of both print media and drawings are their tactility. Within a controlled environment, the original I modi drawings would have been stored away from prying eyes, held in albums, only to be engaged with through the hands of an elite collector and in the company of peers educated in how to “correctly” interpret its imagery. Kept in albums, there is an aura of concealment; the images are “clothed” in their aristocratic context. In this manner, engaging with the drawings would have been an act of unclothing, though permissible for elite viewers. This engagement becomes problematic once the singular drawings are circulated in printed reproduction. Prints are ostensibly two-dimensional, but to engage with prints is to collect, hold, and possess them in a tactile manner. Like Pygmalion, the viewer-as-handler imbues life into the figures and their sexual exploits. Enacting this Pygmalion-like fantasy through an imaginative engagement, the figures become real fleshy beings that can be physically touched, engaged with, and possessed. Thus, the entire viewing experience of I modi is multisensory; the figures in the prints encourage real and imagined tactile responses, much like the sculptural herms. Ultimately, through this tactile engagement, the print and its figures are transformed into objects the viewer can possess.25

The real and imagined possession of I modi would have therefore elicited arousal and potentially sinful responses. This was exacerbated when Pietro Aretino paired Raimondi’s prints with sexually explicit sonnets in 1526.26 In Position I’s sonnet, Aretino provides both a male and female voice, perhaps to widen the intended implicit viewership to include women (fig. 8).27 Nevertheless, Aretino’s female character vocalizes her desire, which grants her a form of agency that would be antithetical to contemporary attitudes concerning women’s ‘proper’ behavior—attitudes that upheld the virtues of silence. Consequently, Aretino’s text encourages the viewer’s engagement with the print as an enlivened image that now speaks, which further places the series in the profane realm, thereby resulting in its censorship.28

I modi was the first instance of a series of unveiled, explicitly sexual imagery circulated in print throughout Renaissance Italy.29 The entire program was novel; from its subject matter to its material form, both aspects played a role in I modi’s censorship. I modi exemplifies the anxieties that images of the sexualized body presented and the dangers of the implicit responses to it by both the elite and non-elite viewers. The printed reproductions of I modi operated within a contemporary discourse of sexuality, the dangers of the senses, and their necessary control.

____________________

Appendix

|

Sonetto I Fottiamci, anima mia, fottiamci presto E se post mortem fotter fosse honesto, — Veramente egli è ver, che se i furfanti Ma lasciam’ir le ciance, e sino al core e se possibil fore, |

| Translation

“Let’s make love, my beloved, let’s make love right away since we are all born for this. And if you adore my cock, I love your pussy; and the world wouldn’t be worth a fuck without this. And if it were decent to screw postmortem I would say: Let’s screw so much that we die of it, and in the beyond we’ll fuck Adam and Eve, who found death so indecent.” “It is really true that if the scoundrels had not eaten that traitorous fruit, I know that lovers would be able to content themselves fully. But let’s stop the chitchat and stick your cock into me up to my heart, and do it so that there my spirit bursts, which on a cock now comes alive, now dies. And if it is possible, don’t keep your balls outside of my pussy, witnesses of every fucking pleasure?” |

Pietro Aretino, “Sonnet I.” In Les sonnets luxurieux du divin Pietro Aretino, 1526. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Translation by Bette Talvacchia, Taking Positions: On the Erotic in Renaissance Culture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999), 199.

____________________

Iakoiehwahtha Patton approaches her scholarship on the Northern Renaissance at the intersection of gender, colonialism, and artistic representations. She completed her BA at the University of Toronto where she was the President of the History of Art Students’ Association and wrote on land, coloniality, and their manifestations in art. Now an MSt student at Oxford, Iako focuses on the gendering of death in the funerary arts of Renaissance France.

____________________

1. Jill Burke, “Nudity, Art, and the Viewer,” in The Italian Renaissance Nude (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018), 70.

2. Burke, “Nudity, Art, and the Viewer,” 69-70.

3. In the Italian Renaissance, the erotic nude emphasized the sensual nature of the body, often veering into the pornographic. As such, these depictions were generally confined to elite circles and their private collections. Not every nude in the Renaissance was erotic; in fact many works of classical or religious themes included nude subjects. Nevertheless, the common thread linking the nude and the erotic nude during the Renaissance was the overarching humanist interest with the human form in art. Sara F. Matthews-Grieco, “Satyrs and sausages: erotic strategies and the print market in Cinquecento Italy,” in Erotic Cultures of Renaissance Italy (Abingdon: Routledge, 2010), 20.

4. Bette Talvacchia, “The Historical Situation,” in Taking Positions: On the Erotic in Renaissance Culture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999), 5.

5. Bette Talvacchia, “Introduction,” in Taking Positions: On the Erotic in Renaissance Culture, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999), ix.

6. See Talvacchia, Matthews-Grieco, and James Grantham Turner, “Marcantonio’s Lost Modi and Their Copies,” Print Quarterly 21, no. 4 (2004): 363–84.

7. Talvacchia, “The Historical Situation,” 4.

8. Talvacchia, 4.

9. Talvacchia, 6.

10. Further study may consider how our understanding of I modi would change depending on the intentions of Giulio Romano and his patron.

11. Around 1524, Pope Clement VII became involved in an effort to regulate artistic production and printed material, especially those deemed indecent. As a result, Marcantonio was briefly imprisoned for his production of I modi in print format. Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the most eminent painters, sculptors & architects, volume 6 (London: Macmillan, 1912-15), 103; Talvacchia, “The Historical Situation,” 6.

12. Talvacchia, 4.

13. Talvacchia, 7.

14. Talvacchia, 6; Vasari, Lives, 105.

15. Matthews-Grieco, “Satyrs and sausages,” 19.

16. Matthews-Grieco, “Satyrs and sausages,” 21.

17. David Freedberg, “The Senses and Censorship,” in The Power of Images: Studies in the History & Theory of Response (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989), 361.

18. Talvacchia (xi-xii) posits that the drawings were most likely for elite collectors, which have not been located. Despite the fact that the first edition engravings no longer survive due to their confiscation and heavy censorship, early modern collecting practices and appetite for the erotic have secured I modi’s afterlife.

19. The Paris Position is compositionally similar to the London Position and Vienna woodcut in showing Position 1. Unfortunately, the Vienna woodcut has been lost. However, the London Position has been attributed to Agostino Veneziano and, as James Grantham Turner (2004) has argued, is likely the source for I modi’s later copies, including, perhaps, the Paris Position. Therefore, the Paris Position likely provides insight into what the original engravings after the Romano drawing looked like.

20. Mary Rebecca Darby Smith and Henry Hopkins, Recollections of Two Distinguished Persons: La Marquise de Boissy and the Count de Waldeck (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1878), 60, 66.

21. James Grantham Turner, “Marcantonio’s Lost Modi and Their Copies,” Print Quarterly 21, no. 4 (2004): 363-366.

22. An important example of the reclining nude is the Venus of Urbino by Titian (1534) including its numerous variations.

23. Freedberg, “The Senses and Censorship,” 355-356.

24. In Book 10 of Metamorphoses, Ovid recalls the tale of Pygmalion, the sculptor who carved his ideal maiden from ivory. After praying to the gods for a wife as beautiful as his creation, Pygmalion’s sculpture is brought to life by Venus. The poem describes Pygmalion’s relations with the ivory figure as erotically tactile: he touches, kisses, strokes, and “[feels] the ivory soften / under his fingers.” As a medium, sculpture is profoundly tactile and the reception of sculpture rests upon its engagement as a spatial object. With its poetic underpinnings in ancient texts, touch is emphasized by early modern Italian writers as an essential component of sculpture’s appreciation. The prints’ intended viewers would have been familiar with both the sacred and profane handling of sculpture, from those collected in the studiolo to movable religious icons. In this way, the herms elicit a tactile response in the viewer, becoming enlivened figures through their visual engagement as sculptured beings. J. D. Reed, “Book 10,” in Ovid: Metamorphoses, translated by Rolfe Humphries (Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2018), 243 (line 286-287).

25. Freedberg, “The Senses and Censorship,” 353.

26. Pietro Aretino. “Sonnet I,” in Les sonnets luxurieux du divin Pietro Aretino, 1526. Bibliothèque Nationale de France; See appendix for sonnet and translation.

27. Aretino’s sonnets would have provided a rare opportunity for women to view images depicting female sexual agency and desire alongside poetry with similar themes. The illustrated sonnets would have represented a departure from more traditional depictions of passive women experiencing sexual encounters, and thus may have encouraged Renaissance women to explore and articulate their own desires.

28. Freedberg, “The Senses and Censorship,” 350-353.

29. Talvacchia, “Introduction,” xi.