Dalí: Disruption and Devotion

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

July 6–December 1, 2024

by Kendall Murphy

The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory (1952-54) by Salvador Dalí welcomes visitors into Dalí: Disruption and Devotion at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA). This painting is an apt work to begin the exhibition, as it prepares the viewer to engage with Dalí’s legacy and to make connections to artwork of the past. Dalí: Disruption and Devotion places a selection of European art from the MFA’s collection in conversation with a number of his significant works to highlight how the artist drew from art history in his practice, while remaining a “disruptor” of the art world.1 The historic European works benefit from this arrangement as much as Dalí’s canvases do because the exhibition fosters a current of surrealism throughout the collection, inviting the viewer to explore all of the art with an eye for the fantastic and enigmatic.

At the start of the exhibition, visitors encounter works including The Temptation of Saint Anthony (about 1650) (fig. 1) by David Teniers the Younger, which features ghoulish creatures such as a bat-like figure and skull-faced monster. The theme of the surreal is sparked by the fantastical creatures invented by Teniers and other earlier artists to represent themes such as temptation, lust, and terror.

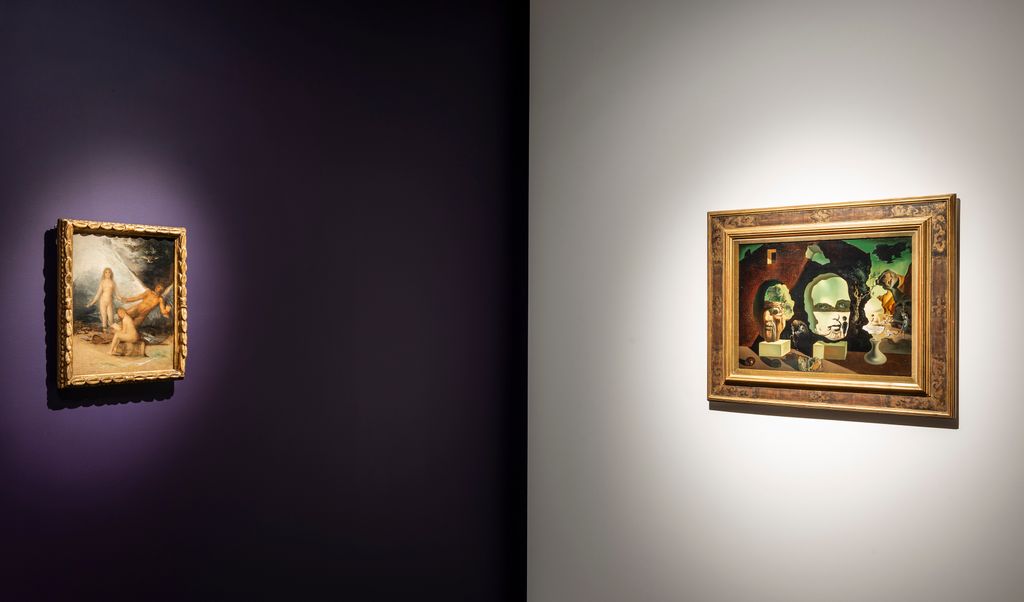

Additionally, the exhibition design fosters a dreamlike atmosphere. The deep purple walls are angled to create dark corners that evoke a sense of privacy or secrecy. Its thoughtful design enhances visitors’ ability to search for the otherworldly in artwork outside of the surrealist canon. The exhibition introduces the viewer to surrealism through a quotation from Dalí, saying “Surrealism is not a movement. It is a latent state of mind perceivable through powers of dream and nightmare.”2 If surrealism is a state of mind, then perhaps artists like Teniers could have tapped into a realm of surrealist fantasy as well.

One of the highlights of the exhibition is Francisco Goya’s Los Caprichos (1799), a series of prints that ridicules the flaws of Spanish society. Dalí’s reinterpretation of Los Caprichos hangs directly across from Goya’s prints, so the viewer immediately notices the bold colors and eccentric details he adds, such as an enigmatic yellow bundle on the woman’s lap in Hypnagogic Rope by Raymond Lull Attached (1973-77). Dalí adds no embellishment to the donkey-man in Goya’s De que mal morira? (Of what ill will he die?) (1799) suggesting that Goya’s surreal character fits into Dalí’s bizarre world. Also, Dalí’s Velázquez’s Painting the Infanta Marguerita with the Lights and Shadows of His Own Glory (1958) hangs adjacent to Infanta Maria Teresa (1653) (fig. 2), which is from the workshop of Diego Velázquez. This comparison allows the viewer to experience a reference point for Dalí’s work up-close and to appreciate the psychological intensity that Velázquez’s associates capture in Infanta Maria Teresa.

The exhibition’s second half delves into Dalí’s biography and the theme of “devotion,” particularly his conversion to Catholicism later in life. Although this is an important topic to explore, the exhibition does not fully address the contradictions inherent in Dalí’s shift towards a traditional faith as he continued his avant-garde explorations of sexual desire and taboo. This period also coincides with Dalí’s reactionary outlook, including his support for the fascist dictator Francisco Franco.3 His monumental painting The Ecumenical Council (1960) (fig. 3), celebrating the coronation of Pope John XXIII, reflects this newfound conservatism. A more comprehensive exploration highlighting Dalí’s conservative positions alongside this work would enhance the themes of disruption and devotion.4

The final artworks presented deal with time and mortality, including Dalí’s Old Age, Adolescence, Infancy (The Three Ages) (1940) (fig. 4). This painting exemplifies his use of “double images,” created through his paranoiac-critical method, which he describes as a “delirium of interpretation.”5 The image label for this work concludes the exhibition by reinforcing the fact that Dalí continued to “acknowledge the artists of past centuries.”6 While the exhibition highlights how Dalí mined past art for inspiration, it overlooks the vibrant community of surrealists, dadaists, and avant-garde artists he engaged with. Citing influences from artists like Yves Tanguy and Max Ernst could have enriched the narrative of Dalí’s sources of inspiration.7

Dalí’s complex works remain thought-provoking, and viewing them alongside his potential inspirations is intriguing. However, the exhibition does not provide a novel understanding of Dalí, skirting the paradoxical nature of his later devotion to Catholicism. Ultimately, visitors leave with an incomplete picture of the artist, as shifting and elusive as the faces in Old Age, Adolescence, Infancy (The Three Ages).

____________________

Kendall Murphy is a first year master’s student at Tufts University. She has held a variety of roles that allowed her to connect the public with new art, including working for the Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival. She is interested in site-specific contemporary art and curation.

____________________

1. Dalí: Disruption and Devotion, introductory wall text, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

2. Dalí: Disruption and Devotion, Fantasy and Nightmare wall text, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

3. Dawn Ades, Dalí and Surrealism (Harper & Row, 1982), 114-17.

4. Ades, Dalí and Surrealism, 114-17.

5. Ades, Dalí and Surrealism, 119. Dalí characterized his paranoiac-critical method as a way to perceive many different forms within one composition by going into a state of delirium. He claimed that this “irrational knowledge” led him to create the shifting arrangements that produce multiple images within his artwork.

6. Dalí: Disruption and Devotion, Old Age, Adolescence, Infancy (The Three Ages) wall label, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

7. Ades, Dalí and Surrealism, 45.