Echoes of Shamanism: Reimagining Tradition and Chance in South Korea

by Hamin Kim

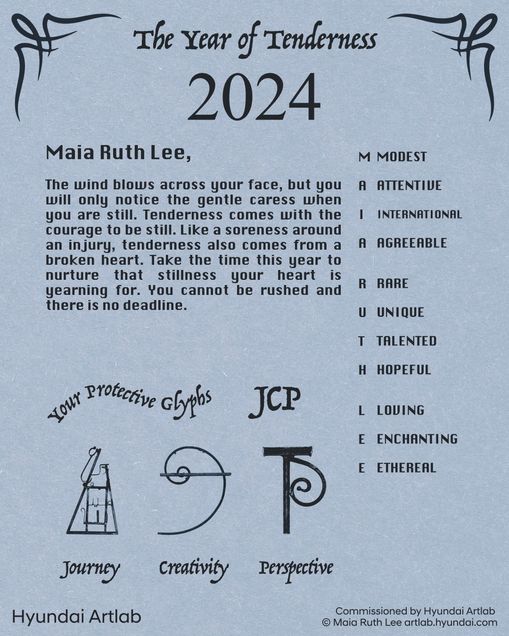

As part of its New Year’s event, Hyundai Artlab commissioned artist Maia Ruth Lee to create a set of symbols predicting fortunes for 2024. This virtual project, titled Glyphoscope 2024, invited participants to select three cards from a set of twenty, each resembling ancient hieroglyphs (fig. 1). The experience, similar to drawing tarot cards, presented a brief interpretive text and a series of keywords that were drawn both from the selected glyphs as well as the initials of the participant’s name, offering a personalized set of affirmations to carry into the New Year. The interactive nature of this project, which combines algorithmic patterns with chance elements, reflects the enduring desire to find clarity amid the uncertainties of the future. Practices like fortune-telling, which are carried out with varying degrees of sincerity, remain deeply ingrained in contemporary society. We continually “test” our luck in various ways, from opening fortune cookies to seeking advice from clairvoyants.

Notions of chance and future prediction have often been dismissed as magical, unscientific, and illogical. Traditional faith systems that embrace such values have been in perpetual tension with the scientific worldview that emerged during the Age of Enlightenment. Especially in many countries that experienced colonization, this tension led to the suppression or transformation of indigenous traditions in favor of modernized (and often Westernized) visions of the future. South Korea followed a similar trajectory. Despite the influence of Confucianism during the Joseon Dynasty (13–19th centuries), and the introduction of Christianity in the late 19th century, shamanism, the primordial religion of Korea derived from Siberia and Northeast Asia, remained deeply embedded in the base of the country’s cultural terrain.1 Even during the period of rapid modernization during the 1960s to 1980s, when the authoritative South Korean government promoted uniformity and the Western standard of development while simultaneously stifling individual creativity, people continued to turn to shamans in times of crisis or uncertainty, relying on the power of luck to avoid misfortune.2

Shamanism saw a resurgence in the early 21st century in the arts as South Korea gradually globalized after the end of the Cold War in 1989 and established a democratic government shortly after. Authoritative values in the past gave way to diversity and cultural heterogeneity, and the contemporary art world moved towards a “global pattern of flow and resistances” rather than the dichotomous view of center versus periphery.3 Artists started to take notice of the potential of shamanism as an apt alternative to a strictly rational, scientific worldview. Their reexaminations found a more fluid, empathetic approach to considering human nature. This new understanding of shamanism was a central theme in the 2014 Seoul MediaCity Biennale, titled Ghosts, Spies, and Grandmothers. The Biennale’s director, Park Chan-kyong, focused on marginalized yet potent entities in society. He explained his decision to juxtapose three seemingly disparate figures:

Spies seen in the movies look attractive, but “spies” (gancheob) in the news are terrifying.4 One should worship god in ancestral ceremonies but stay far away from the ghosts you encounter during the night. Grandmothers should be respected, but in reality, they are expelled outside the huge wave of praise for the young. You notice them sometimes, but they are generally difficult to spot; or one does not wish to see them, or should not see them. They are skilled in silence and possess top-level information. Hence they cry out, confess, disclose or testify. They easily become paradoxical beings according to the situation.5

The convergence of the three symbolic figures—ghost, spy, and grandmother—underscores Asia’s ongoing effort to transcend forcefully inserted Westernized influences and reclaim its original heritage by positing a “modernity against modernity.”6 Park’s theme was not incidental; it was the culmination of his own documentary, Manshin: Ten Thousand Spirits (2013), which unraveled the complex and ambivalent emotions surrounding shamanism in Korea through the life of Kim Keum-hwa, the country’s most renowned manshin (shaman). The predominantly female demographic of Korean shamans ties to the figure of the “Grandmother,” who venerates shamanistic deities or “Ghosts,” and who has witnessed the tumultuous 20th-century history in Korea, where many formative and socio-political events were often centered around “Spies.”

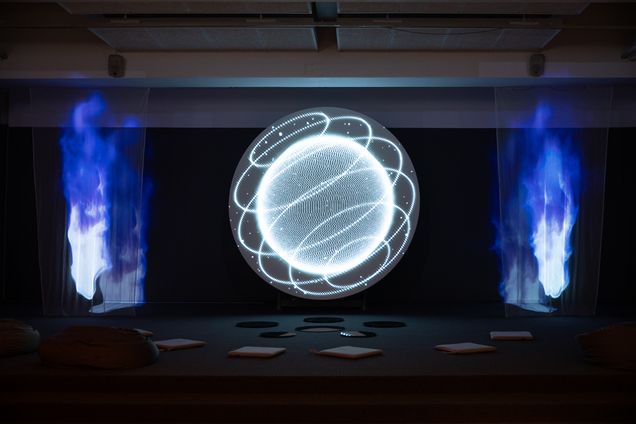

Shamanism experienced another resurgence during the 2020 Covid pandemic. In 2021, the Ilmin Museum of Art opened their exhibition entitled Fortune Telling, which provided an outlet for exploring and processing collective anxieties in a time marked by uncertainty. The exhibition drew on shamanistic practices as well as traditional East Asian philosophies, including the concept of yin and yang, and the five elements (wood, fire, earth, metal, and water), which comprised the fundamental categories in Chinese cosmology to understand the universe. The harmony and balance of these forces were thought to govern the natural world and human life. This exhibition exemplified how what was once seen as occult has been recontextualized in contemporary art as a way to bring comfort to the audience. As part of the show, a shaman with an art educational background produced a museum audio guide and artists invited participants to engage in saju readings (fortune-telling based on one’s birth date) as part of a performance.

The exhibition space was divided into two sections, “fate” and “counseling,” suggesting that for the curators, these concepts are interrelated: fate serves as the foundation of existence, while counseling offers therapeutic guidance in navigating fate and finding inner peace. Indeed, the exhibition is also living proof that what was once viewed as an occult practice of communicating with otherworldly entities became more accessible with the popularization of diluted forms such as saju, tarot readings, and face readings—practices that were considered safer and relatively more scientific—grounded in statistical reasoning rather than ghostly communications. Fortune Telling offered visitors a way to reflect on the emotional and psychological challenges of the pandemic, bridging ancient philosophies with contemporary concerns (fig. 3). This renewed interest in shamanism and traditional cosmology highlights how people seek comfort and meaning from deeply rooted cultural practices, especially during times of crisis.

Although shamans remain somewhat intimidating figures due to their perceived possession by spirits, artist Haegue Yang offers a more sympathetic interpretation. She notes that “today’s shamanism has been tainted by a culture of unscientific superstition or prayers for personal prosperity. In the past, shamanistic rituals (guts) were performed for communal well-being—to bring rain, end droughts, or ensure the safe return of those who had left their homes.”7 Her ongoing project, Mesmerizing Mesh (2021–), folds and cuts pieces of traditional Korean paper, evoking symmetrical ritual paper props used by shamans (figs. 5-6). The mass of works explores shamans as intermediaries between the divine and humanity, although the artist laments that shamans themselves often remain marginalized.8

However, Yang also poignantly points out that the preservation of tradition may have political connotations, particularly in parts of Europe, where it is sometimes used to justify exclusion and anti-immigration sentiments.9 Nonetheless, many non-Western countries, especially in the Global South, share similar sentiments toward shamanism as those illustrated above in the case of South Korea, including an ambivalence toward rooting their historical narratives that were once superimposed by imperialism and capitalism. The quest to reconnect with their roots remains ongoing.

Understanding shamanism and its reception in the contemporary world is far from straightforward. It is a complex and multi-layered process, entangled with the legacies of imperialism, questions of legitimacy and self-doubt, and the unpredictable nature of future prediction. Despite this complexity, the exhibitions and participating artists highlight the potency of shamanism as a transgressive and healing force embedded in the lives of many. By looking into works on both institutional and individual levels, Korean contemporary art in the context of shamanism deals with defying logical explanations and offering a path for those seeking meaning in an increasingly uncertain world.

____________________

Hamin Kim (she/her) is a PhD student at Boston University whose research centers on modernization and globalization in Korean art from the 20th century onwards, with particular emphasis on Korea’s cultural exchange with Japan and the United States and the history of performance in Korea.

____________________

1. The survival of Korean Shamanism amidst the influx of Christianity is detailed in Oak, Sung-Deuk, “Healing and Exorcism: Christian Encounters with Shamanism in Early Modern Korea.” Asian Ethnology 69, no. 1 (2010): 95-128.

2. Although sporadically, artists continued to investigate shamanism in their practices during the 20th century. The most salient efforts were made in the Minjung (People’s) arts movement during the 1980s but also through individual efforts including the photographer Lee Gapchul’s Confliction and Reaction series (1990-2002) as well as Lee Seungtaek’s Wind series (1967- ) etc.

3. Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization (University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 46-47.

4. In the original Korean statement, Park differentiates between Western “spies” and “spies (gancheobs).” The former evoke Hollywood’s James Bond archetype—sleek and glamorous—while the latter refer specifically to North Korean operatives who infiltrate South Korean society to steal sensitive information. These North Korean spies are often portrayed as petty and unrefined, embodying a dirtier, more sinister image.

5. Park Chan-kyong, “Why ‘Ghosts, Spies, and Grandmothers’?”, Accessed September 23, 2024, http://archive.mediacityseoul.kr/2014/en/introduction/2014theme/ghost-spy-grandmother/.

6. This is not to suggest that all Western influences introduced in Asia were imposed by force. However, the remnants of colonialism, as opposed to voluntary cultural exchanges, have left more profound impacts on later generations. My aim is to highlight the involuntary aspects of Western influence rather than to dismiss Western influence in Asia as wholly negative. Additionally, the phrase “modernity against modernity” is derived from the original Korean title of the Seoul MediaCity Biennale.

7. Unless otherwise indicated, translations are the author’s. Jaeyeon Cho, “Double Souls, Dialectic of the Truth: SMK – Statens Museum for Kunst Haegue Yang solo exhibition, Double Soul,” Art in Culture [translated from Korean], April 2022, 166-67.

8. “Beyond Paganism and Shamanism: Haegue Yang in Conversation with Kirsty Bell on Mesmerizing Mesh”, July 2, 2022, Haegue Yang, accessed on September 2, 2024, http://www.heikejung.de/list_of%20texts/KirstyBellHaegueYangMM.pdf.

9. “Haegue Yang: Handles, Haegue Yang Interview,” W Magazine [translated from Korean] (November 4, 2019), https://www.wkorea.com/2019/11/04/%EB%A7%9D%EA%B0%81%EC%9D%98-%EC%86%90%EC%9E%A1%EC%9D%B4/ (accessed on September 20, 2024).