editor’s introduction

by Catherine Lennartz

What lies beyond the veil? Some version of this question has inspired people from every walk of life to use mortality as a source of inspiration. No matter our beliefs, death and its unknowns have yielded varied forms of artistic production that remain evocative to this day. Rituals surrounding death permeate human history and make up a large part of the earliest examples of human creative production that we study as art and architectural historians. From funerary complexes to sacred objects and texts, from intuition and dreams to meditation and self-discovery, there is no doubt that imagining what exists beyond our lives has been a fruitful endeavor. Just south of Stockholm, Sweden, a cemetery called Skogskyrkogården marries architecture and landscape in its modern take on these age-old questions (fig.1).

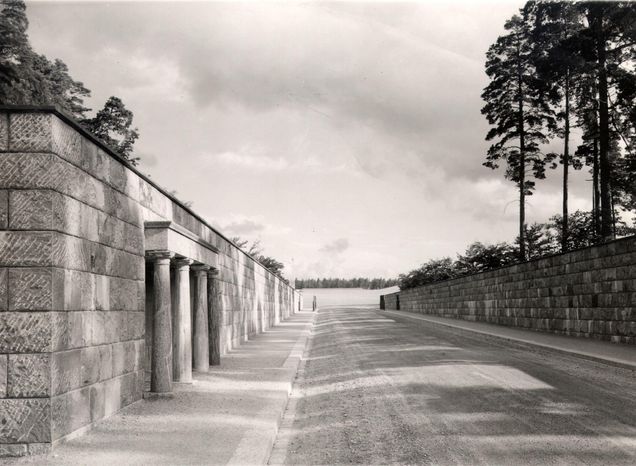

The Woodland Cemetery, as it is known in English, utilizes landscape and nature to create a transitional space for people to come to terms with the new world they find themselves in after losing a loved one. It was built in the first half of the twentieth century following the designs of Erik Gunnar Asplund and Sigurd Lewerentz.1 Their partnership—though not without disagreements—resulted in a design that Caroline Constant describes as “imparting a sense of serenity in the face of death through reconciliation with nature.”2 The atmosphere is set by the entrance: a walled, semi-circular space that leads visitors into a long, narrow walkway. The retaining wall, standing around twelve feet tall, is topped by trees, evoking the sense of being below ground. As one walks down the road, the walls shrink, or rather the path rises, until an open grassy area is revealed (figs. 2-3). Coming into view to the left are the main chapels and crematorium serving the cemetery. Other chapels are spread across the grounds, offering a variety of options for memorial services of all kinds, religious or secular. The rest of the cemetery is covered with tall pine trees, creating a sheltered canopy over the gravestones occasionally crisscrossed by open avenues. No buildings stand taller than the trees across the grounds.

The largest chapel, the Chapel of the Holy Cross, echoes the entrance path’s transition from contained to open in the way it holds funerary services (fig. 4). Guests enter the chapel from an interior side door and sit facing a large curved and frescoed wall depicting scenes of Viking funerary practices. The floor angles down gently towards the altar where the coffin is laid. At the end of the service, guests are invited to walk up the sloping floor to the back of the chapel, where curtains are drawn, flooding the chapel with light and revealing a glazed wall protected by a wrought-iron grill. Both the window and the grill are then lowered into the ground, opening the whole wall onto a covered porch. At the center of this porch, in an opening reminiscent of a Roman compluvium, sits the Resurrection Monument, a bronze sculpture reaching for the sky. The porch sits at ground level, granting access to the lawn, paths, and lily-pond beyond. The whole funeral service thus transitions from a protected interior space for the duration of the ceremony and eulogies to a procession up and gradually out into nature. Each space offers the opportunity for pause, as the mourner wishes.

Figure 4. Virtual visit of Heliga korsets kapell (Chapel of the Holy Spirit) (2015). Photos Tommy Hvitfeldt.

Skogskyrkogården presents innumerable in-between places for reflection without ever claiming to offer explanations or answers. The cycles of dark and light, closed and open, that visitors experience during their time at the cemetery mirror the process of grieving, with darker and brighter moments sometimes emerging unexpectedly. The result is a space dedicated to the dead that cares deeply about what it can provide for the living.

In this issue, we have gathered scholarship that engages with artists, patrons, and institutions that question what lies beyond human perception: be it divinity, (im)mortality, or the supernatural. Our three feature essays investigate artistic practices that pose fundamental questions about our beliefs surrounding death and those who have passed. Drawing on the intersections of religious and artistic patronage, murder, architecture, and musical compositions, William Chaudoin describes the complex ways in which a sixteenth century nobleman, Carlo Gesualdo, sought to secure salvation for his soul. Centered around the commission of an altarpiece, this analysis showcases a belief in artistic devotion that could secure forgiveness in the afterlife for sins committed on earth. In an essay that turns its attention to the moments following death, Gillian Yee looks to the intimate photographs David Wojnarowicz took of Peter Hujar—his mentor and lover—moments after his death from AIDS-related complications. Here we are invited to reconsider our relationship with death and the passivity of the dead body through photographs that each show only a small part of Hujar. Each image holds meaning and identity, rejecting the binary of life and death to suggest alternative ways of being. Hamin Kim explores the myriad ways artists in Korea engage with fortune, fate, and chance through new practices echoing older forms of Shamanism. Through a series of examples, we begin to understand the dialogue between Korean traditions and Western modernity that underpin many of the resurging practices; the results allow for a more fluid understanding of humanity.

Sayak Mitra’s creative practice navigates the space between being a Bengali Indian and a conditional resident of the United States. In his paintings and installations, we are confronted by the illusory nature of the promises of neo-liberalism through materials that speak to both life in West Bengal and in Boston. Cultural identity is thus constructed through the material output of extractive economies and global corporations.

In our research spotlight, Elaigha Vilaysane emphasizes the importance of spatiality and context in the display of ancient Chinese funerary objects. Looking at two case studies from Western universal survey museums, Vilasayne’s dissertation research draws on a wide range of scholarship to analyze the impact of object labels, surrounding artworks, modes of display, gallery layout, and expected visitor behaviors in effectively conveying the religious and cultural functions of these objects.

This issue would have been incomplete without a review of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston’s exhibition dedicated to the work of Salvador Dalí. This exhibition proposes to connect Dalí’s work to that of many of his predecessors, often inviting a recognition of surrealist themes in earlier works. Kendall Murphy recognizes the value of expanding the idea of surrealism as a state of mind shared by artists beyond the traditional limits of the movement, but she warns against an oversimplification of Dalí’s turn towards Catholicism and conservatism later in life—a surprising lacuna considering the exhibition’s themes of disruption and devotion.

Though what lies beyond the veil might remain obscured, our authors have shown that this is not an obstacle to scholarship; rather, it reveals aspects of human nature through the ways we interact with each other and the world in the face of unanswered questions. This is a small reminder that we are always surrounded by other worlds: we can glimpse them when we open ourselves up to the points of view of the individuals, collaborators, colleagues, and communities that surround us.

____________________

Catherine Lennartz is a PhD student in the History of Art and Architecture at Boston University. Her research explores the intersection of exhibitions and memorials, memory-focused art, and remembrance, especially as they relate to human rights.

____________________

1. Kieran Long, Johan Örn, and Mikael Andersson, Sigurd Lewerentz: Architect of Death and Life, trans. Anna Paterson (Park Books, 2021), 26.

2. Caroline Constant, The Woodland Cemetery: Toward a Spiritual Landscape (Byggförlaget, 1994), 49.