From the Tomb to the Museum Plinth: Chinese Burial Objects on Display in the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art

by Elaigha Vilaysane

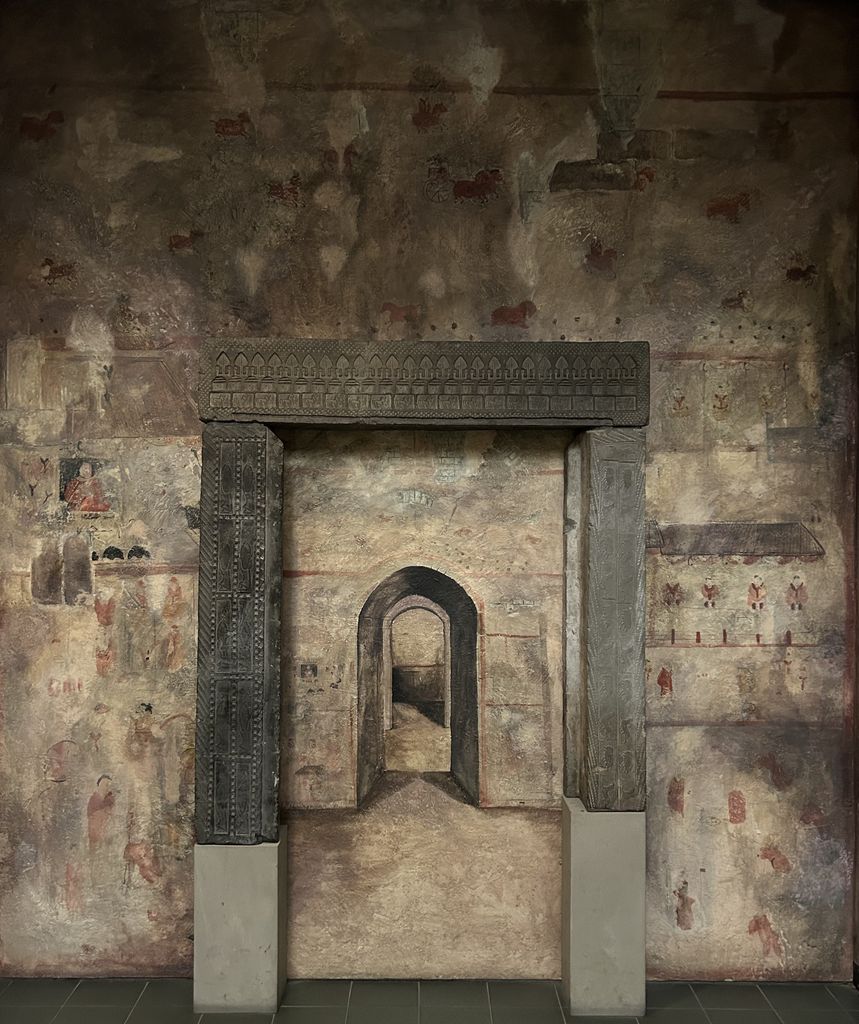

In his 2009 journal article entitled “Enlivening the Soul in Chinese Tombs,” Chinese art historian Wu Hung contends that most European and American museums do not display Chinese funerary objects in their ritual and architectural context.1 As a result, the decontextualized display of these artifacts limits an understanding of their original function.2 Museums in the West already subject Chinese objects to a binary of display, either within the pre-existing framework of Western art or classified as anthropological or ethnological objects.3 For Chinese burial objects, this binary becomes further exacerbated as their identity is defined as “art” or “artifact” when they are divorced from their original archaeological contexts.4

My Master’s dissertation in the History of Art and Archaeology of East Asia examines how Chinese burial objects are displayed in two Western universal survey museums’ galleries: the Charlotte C. Weber Gallery at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City (Met) and the T.T. Tsui Gallery at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (V&A). These universal survey museums are characterized by their globally diverse collections spanning a geographically broad range of art history.5 To my knowledge, no existing research compares these two galleries. I critique these galleries in their roles as cross-cultural communicators. The efficacy of the galleries is determined by whether the displayed Chinese burial objects’ purpose and function is clearly conveyed to visitors, and if these objects are contextualized within dynastic Chinese history and culture through the semiotics of the space—such as object descriptions and accompanying wall texts—as well as within the space itself, including the architecture and other visual informants impacting their display.

Religious and philosophical dynastic Chinese beliefs informed the practice of utilizing burial objects to activate the tomb into a spiritual space for the deceased’s soul as a “microcosmic representation of the universe.”6 These burial objects, known as mingqi are “[…] portable tomb furnishings, mainly objects and figurines, that are specifically designed and produced for the dead.”7 Mingqi are largely what both the Met and the V&A display in their respective Chinese “burial” galleries.

The interpretation of sacred objects, like mingqi, is notably impacted by how they are displayed within a museum. Art historian Gretchen T. Buggeln identifies a trifold dynamic of the display of sacred objects in museums as a relationship between the viewer, who is informed by both the museum’s interior and exterior architecture, and the object’s innate characteristics.8 Buggeln expands upon the influence of the museum’s architecture on the visitor experience by quoting museologist Carol Duncan, “[Museums] contain numerous spaces that call for ritual behavior, ‘corridors scaled for processions, halls implying large, communal gatherings, and interior sanctuaries designed for awesome and potent effigies.’”9 In addition, there exists a subconscious museum etiquette requiring visitors to keep low volume levels and to slowly circumambulate the gallery, which both exemplify ritual-like behavior.10 The influence of spatiality on the museum visitor’s understanding of sacred objects through “spatial semiotics [that] reinforce the devotional context,”11 such as the glass case or plinths, emphasizes the sacredness of these objects by distancing the viewer through a physical barrier.12

In displaying sacred objects, curators are tasked with representing intangible religious beliefs. Religious studies scholar Chris Arthur has addressed the general skepticism of how much one can depend on the gallery to provide a comprehensive overview of specific religious beliefs and practices through the display of their respective religious objects. Yet he is hopeful that an object’s description, albeit short in nature, can provide the visitor with a starting point for understanding.13 Although the original sacred environment can never be fully recreated, the museum remains responsible for presenting their collection of sacred objects within an atmosphere of respect.14 This is important to consider in forming our understanding of Chinese burial objects on display and especially the museum’s efforts to communicate their original sacred significance to the deceased.

Given the nature of its collection, my dissertation concludes that because the Charlotte C. Weber Gallery at the Metropolitan Museum of Art mostly contains ceramic mingqi from the Han and Tang Dynasties, the gallery is curated into a linear, chronological mode of display identifying and highlighting the progression of mingqi as burial art. Alternatively, the diversity of the Victoria and Albert Museum’s collection (spanning from the Neolithic era to the Ming Dynasty) allows its “burial” section of the T.T. Tsui Gallery to communicate with five other thematic sections of the gallery: Temple and Worship, Living, Eating and Drinking, Ruling, and Collecting. Thus, the T.T. Tsui Gallery presents mingqi as artifacts. By cohesively contextualizing the function of Chinese funerary objects in Chinese life and culture, the curation of the T.T. Tsui Gallery encourages the viewer’s visualization of the spiritual space, hence a more effective method for visitors to learn about the importance and function of Chinese funerary objects.

____________________

Elaigha Vilaysane received her BA in Chinese Language and Literature and Art History from the George Washington University in May 2023. She has recently completed her master’s degree at SOAS, University of London in History of Art and Archaeology of East Asia with a concentration in Chinese studies.

____________________

1. Wu Hung, “Enlivening the Soul in Chinese Tombs,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no 55/56 (Spring – Autumn, 2009): 41, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25608834.

2. Wu, “Enlivening the Soul in Chinese Tombs,” 41.

3. Steven Conn, “Where is the East? Asian Objects in American Museums, from Nathan Dunn to Charles Freer,” Winterthur Portfolio 35, no 2/3 (Summer – Autumn, 2000): 157-58, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1215363.

4. Ronald L. Grimes, “Sacred objects in museum spaces,” Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses 21, no. 4 (1992): 422-23.

5. Carol Duncan and Alan Wallach, “Chapter 3: The Universal Survey Museum,” in Museum Studies: An anthology of contexts, ed. Bettina Messias Carbonell (Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2004), 54.

6. Wu, “Enlivening the Soul in Chinese Tombs,” 22.

7. Wu Hung, “Materiality,” In The Art of the Yellow Springs (University of Chicago Press, 2010), 87.

8. Gretchen T. Buggeln, “Museum space and the experience of the sacred,” Material Religion 8, no. 1 (2012): 45, https://doi.org/10.2752/175183412X13286288797854.

9. Buggeln, “Museum space and the experience of the sacred,” 37.

10. Buggeln, “Museum space and the experience of the sacred,” 37.

11. Louise Tythacott, “Curating the Sacred: Exhibiting Buddhism at the World Museum Liverpool,” Buddhist Studies Review 34, no. 1 (2017): 116, http://www.doi.10.1558/bsrv.29020.

12. Tythacott, “Curating the Sacred: Exhibiting Buddhism at the World Museum Liverpool,” 123.

13. Chris Arthur, “Exhibiting the Sacred,” in Godly Things: Museums, Objects, and Religion, ed. Crispin Paine (Leicester University Press, 2000), 5-6.

14. Tythacott, “Curating the Sacred: Exhibiting Buddhism at the World Museum Liverpool,” 130.