news

Conceptualizing a Maritime Salvage Culture

Crystal Currents: The Indo-American Ice Trade and Colonial Comfort in Tropical Nineteenth-Century India

editor’s introduction

Submerged Histories: Watery Archival Practice in Renee Royale’s Landscapes of Matter

notes about contributors

Isamu Noguchi: Landscapes of Time

An Oceanic and Imperial Treasure: The Southern Song Oyster-Mountain Celadon Bowl

The Abyss Stares Back: Encounters with Deep-Sea Life

Sensory Entanglements: Knowledge Rituals in the Digital Age

by Elise Racine

In the liminal space between the physical and digital realms of human thought and creation, our relationship with knowledge undergoes a profound transformation. Through this series of works, I examine how emerging technologies reshape not just our access to information, but the very physicality of our engagement with it. Together, these pieces explore the sensory dimensions—touch, sight, sound—of contemporary knowledge transfer, asking how the digital age reshapes materiality, intimacy, and the archive while situating the viewer at the crossroads of tradition and innovation. The transition from bound volume to infinite scroll represents more than a shift in medium—it fundamentally alters our sensory and cognitive relationship with knowledge itself.

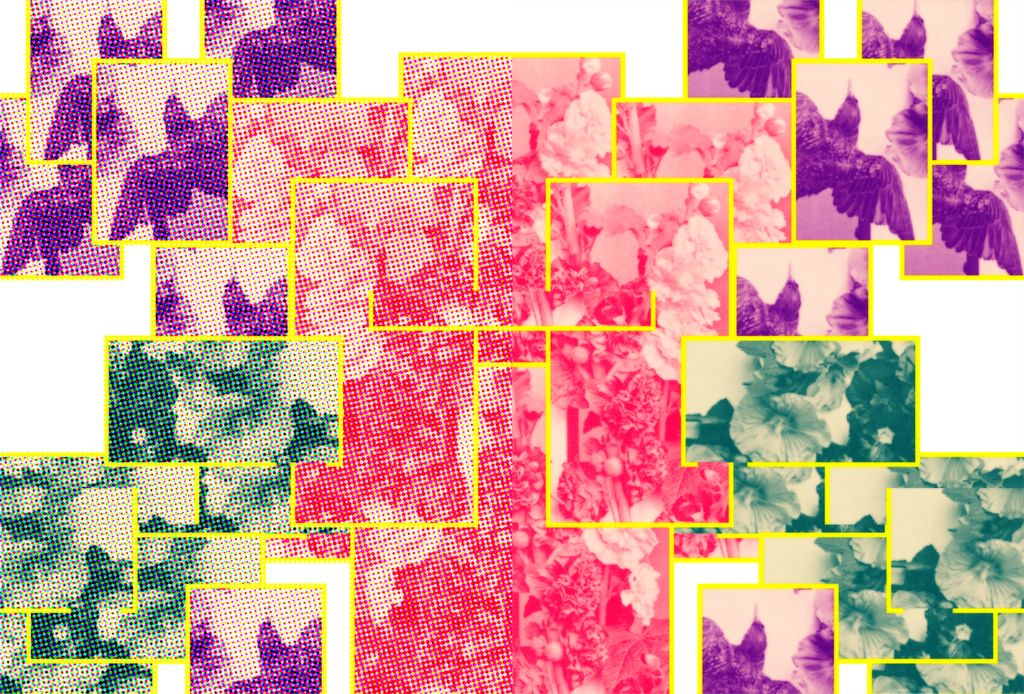

Figures 1-3. Elise Racine. A Book by Any Other Name (2024), Folio Fragments (2024), and Field Guide Distortions (2024). Digital collages involving archival images, photography, digital art, and artist-generated annotations.

A Book by Any Other Name (fig. 1) juxtaposes a weathered physical tome with its digital counterpart, highlighting how artificial intelligence reinterprets the essence of “book-ness.” The textured, ornate cover of the book—a Bible from ca. 1602—stands in stark contrast to the sleek, minimalist e-reader interface. Still, both objects serve as vessels for human knowledge and demand their own form of tactile engagement. The artist-generated yellow frames mimic the bounding boxes used in AI object detection. The accompanying annotations reveal how algorithms “see” and interpret visual information, highlighting elements the system identifies as significant. The boxes have the added benefit of drawing attention to how our eyes and fingers must navigate differently across these surfaces. Here we engage with the tension between physical and digital tactility—between the controlled, bounded experience of turning a page and the potentially endless scroll of digital content.

Meanwhile, Folio Fragments and Field Guide Distortions (figs. 2-3) employ fragmented compositions to further examine how digital media disrupts traditional ways of organizing and accessing information. Building again on the pattern of AI annotations, these pieces feature yellow boxes that highlight the tension between machine and human interpretation. The geometric abstraction framing the original archival image in Folio Fragments causes new details and patterns to emerge. In Field Guide Distortions, this effect is captured by AI annotation boxes whose contents and borders dissolve into pixels and halftone displays, further blurring the distinction between digital and analog representation. As vibrant colors bleed across these boundaries, the image becomes a metaphor for the chaos and the creativity inherent in digital knowledge systems.

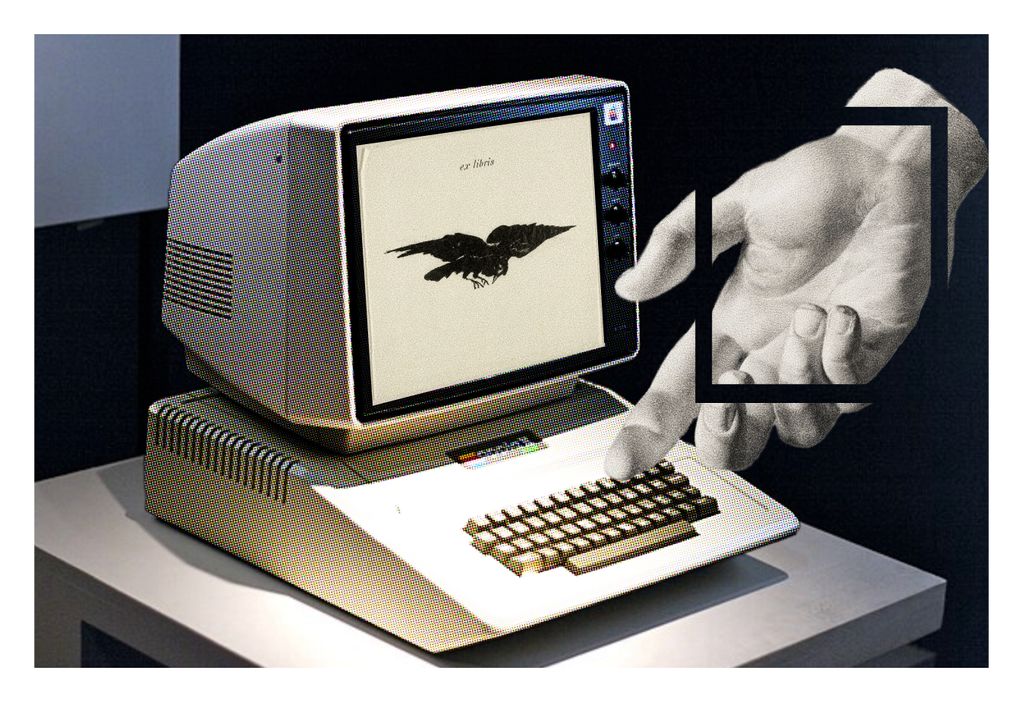

Figure 4. Elise Racine. [Crow]dsourced (2024). Digital collage involving archival images, photography, and digital art.

By placing a traditional ex libris crow within the frame of an early personal computer, [Crow]dsourced (fig. 4) reflects on the shift from individual, physical possession to shared, digital knowledge generation. Historically a mark of ownership, the ex libris bookplate is recontextualized in an era of collective authorship and the crow, long symbolic of intelligence and memory, suggests our enduring drive to gather and share knowledge, even as the means of doing so evolve. Meanwhile, the fragmented hand in the corner speaks to the intimate gestures, or human “touch,” that persist in these virtual spaces and the collaborative nature of such acts.

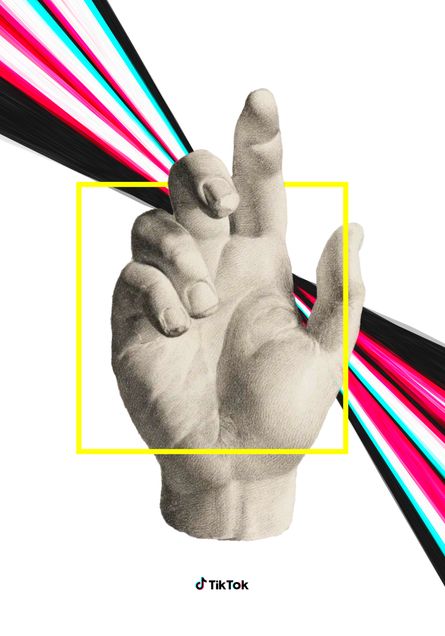

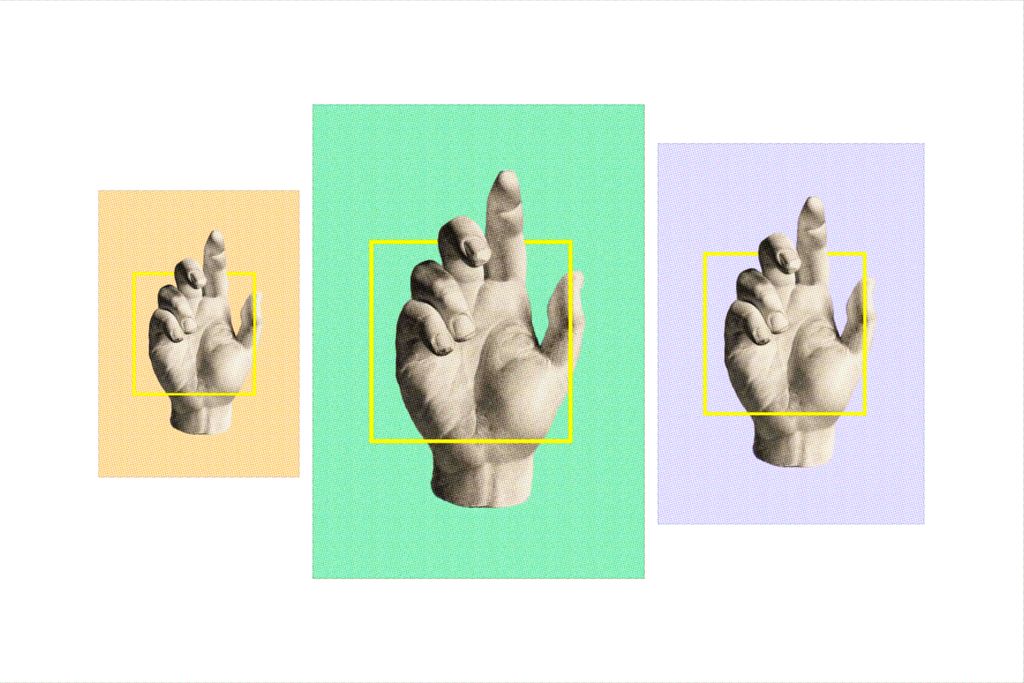

Figures 5-6. Elise Racine. At the Altar (2024) and Holy Trinity (2024). Digital collages involving archival images, digital art, and artist-generated annotations.

In At the Altar and Holy Trinity (figs. 5-6), we again see the hand. Originally a symbol of religious iconography, it now also mirrors the anatomical positions for scrolling, swiping, and liking. These actions—scroll, swipe, like—form a modern “holy trinity.” While digital interfaces may seem to distance us from the materiality of knowledge, we must also consider how they create new forms of sensory engagement, ones that merge historical devotional gestures with contemporary, technologically mediated rituals.

Figure 7. Elise Racine. On Loop (2024). Video art playing on an infinite loop.

On Loop and Scroll A(n)d Infinitum (figs. 7-8), extend this exploration, particularly the destabilizing, distortive nature of digital consumption, with motion and sound. Both were previously on view as Infinite Objects video prints in Boundless: An Exhibition of Book Art hosted by the Arts Galleries at the Peddie School in New Jersey.1

On Loop captures TikTok as a contemporary vessel for knowledge-sharing, pairing the hypnotic feed with an audio soundscape of clicks and taps. Through its fragmented structure, the piece mirrors how our attention splinters across infinite content streams. Scroll A(n)d Infinitum critiques the infinite scroll as a digital reading experience by featuring a long-form article endlessly looping, with glitch aesthetics and chromatic aberrations visualizing the sensory overload of contemporary interfaces. As text fragments blur and degrade, nearly reduced to a binary code of 1s and 0s, the piece highlights how machines can now “read” these digital texts even as they become illegible to human eyes. With the rise of Large Language Models, it poses the question of whether we are creating digital content not just for human consumption, but for an emerging audience of artificial readers—algorithms that process and interpret our knowledge in ways fundamentally different from human cognition.

These moments of friction are precisely why the relationship between physical books and digital interfaces is so compelling. This goes beyond how our fingers engage differently with each medium to how we navigate and control our progression through content and how these sensory interactions shape our reading experience. I strive to recreate the sensation of “doomscrolling,” a phenomenon that arises from the absence of natural endpoints that we find in traditional reading material. The slight discomfort or disorientation viewers might experience navigating this essay points to our larger cultural moment of adjustment to these evolving forms of knowledge transmission.

This work invites viewers to consider not just how we read and learn in the digital age, but how these new practices reshape our fundamental relationship with knowledge—at once more immediate and more mediated, more accessible and more fragmented, more tactile and more ephemeral. Perhaps most striking is how contemporary knowledge is simultaneously in a perpetual state of transition yet immortalized in the digital ether—forming new archives that train the next generation of machines.

Figure 8. Elise Racine. Scroll A(n)d Infinitum (2024). Video art playing on an infinite loop.

____________________

Elise Racine is a Washington, DC-based multidisciplinary activist, emerging artist, and PhD candidate at the University of Oxford. Using arts-based methodologies, her research examines the socio-ethical implications of emerging technologies, like artificial intelligence. Recent exhibitions include: The Bigger Picture (Beta Festival 2024, Ireland) and Unearthing (Sims Contemporary, NYC).

____________________

1. Infinite Objects are freestanding displays housed in acrylic that permanently loop one video. They can be picked up and handled, allowing viewers to physically engage with otherwise ephemeral digital media. In other words, they make the ephemeral tangible again.

Multisensory Experiences in Thomas Jefferson’s Plantations

by Mya Rose Bailey

I first heard the ringing of the Great Clock at Monticello in the dead of summer. The deep, steady resonance of the gong felt as though it could wipe the sweat from my back. I stared as its hammer, now muffled but still deafening in its strike, emanated three low reverberations. And then my three o’clock tour began. I was brought to Monticello by my Master’s thesis, which was concerned with how time and sound were constructed in two of Thomas Jefferson’s plantations in efforts to control Black enslaved labor. By exploring the sensory experience of enslavement through material culture and decorative arts, there is an opportunity to mentally deconstruct objects designed to present unnatural systems—such as race-based enslavement—as intrinsic and necessary to eighteenth- and nineteenth-century life.

Designed by President and enslaver Thomas Jefferson, the Great Clock still stands, as it did for Antebellum audiences, as a marvel of Jefferson’s ingenuity and creativity. Its wooden double-faced body serves as a daily point of reference for internal and external viewers. Once allowed inside Monticello, audiences of the Great Clock can determine the exact time of day through a visible hour, minute, and second hand (fig. 1). Outdoor witnesses, however, only see a single hour hand on the clock’s exterior face (fig. 2). The Chinese gong housed on the roof of Monticello chimes the corresponding hour, reverberating across six miles of the plantation, according to Peter Fossett, one of the nearly six hundred Black people Jefferson enslaved in his lifetime.1

The gong sonically enforced a schedule of labor that could be heard and followed voluntarily by anyone present but was involuntarily heeded by the enslaved community. A constant awareness of the gong’s count signaled when a day’s work began at dawn and ended at dusk, as well as breaks for meals, curfews, and allotted “free” time.2

Monticello in Charlottesville, Virginia and Poplar Forest in Bedford County, Virginia were Jefferson’s most prominent homes and plantations, with a combined ten thousand acres of farmland and nearly two hundred people at a time enslaved across both. To aid in managing this scale of property, Jefferson designed, deployed, and depended heavily on time-keeping and time-telling devices to organize and communicate work schedules to all present laborers.3 Time-telling is best exemplified by objects such as the Great Clock, as its grandeur, permanence, and immovability demand recognition as the standard of regulation in its positioned environment. Multiple case and shelf clocks were also present in more intimate settings for enslaved laborers, specifically the kitchens at both Monticello and Poplar Forest.4 The striking difference between the timekeeping devices’ scale in these spaces suggests the ability of clocks to oversee the bodies, acting as tools of regulation as opposed to entertainment. In contrast to the Great Clock—which would have both delighted and fascinated free visitors to Monticello—these small clocks governed and maintained enslaved bodies and their labor.

One can imagine the rhythmic ticking of a shelf or case clock within the soundscape of a kitchen often occupied by a single cook. The Jefferson family would have set expectations for when a meal should be served, as signalled by the swinging of a hammer chime. Such meals — which would have been made countless times by Monticello cooks — were created both through embodied knowledge and alternative modes of timekeeping (song, prayer, etc.)

This request for a prepared meal at Poplar Forest was commanded by a single brass bell rung by Jefferson that was later excavated from Poplar Forest’s main house.5 The disembodiment of these sounds, and the labor Jefferson demanded through them, is essential in understanding how linear perceptions of time and constructed soundscapes were presented as intrinsic to the hundreds of people he enslaved.

Jefferson’s own understanding of time as both linear and irretrievable was largely informed by European philosophers within the Age of Enlightenment and cultivated his disdain for idleness.6 Jefferson’s subsequent compulsion for efficiency manifested in strict schedules for himself, his family, and the people he enslaved. This temporal imposition was likely disorienting due to the fact that in the Bight of Biafra, where most of his enslaved laborers were taken from in the eighteenth century, time was regarded as unregulated and multidirectional.7 This encourages us—in the contemporary moment—to reconsider the ways enslaved people may have measured, felt, and sounded time within a day. Most importantly, it begs a reconsideration of how we and Jefferson expect time and the sensorium to function for enslaved people. Jefferson himself noted the vibrancy of music and nightlife of those he enslaved in his only full-length book, Notes on the State of Virginia, stating “a black, after hard labour through the day, will be induced by the slightest amusements to sit up till midnight, or later, though knowing he must be out with the first dawn of the morning.”8 The presence of music—specifically music at night, away from the audible demands of labor—suggests another layered soundscape that was not only experienced communally amongst the enslaved but produced by and for themselves as well.

My approach to the sensory experience of enslavement rests upon the acknowledgement that Monticello, Poplar Forest, and the consequent soundscapes of these plantations are all, even loosely, predicated upon slavery in that they only exist because of and to maintain enslavement. Thus, in my interpretation of these constructed temporalities, landscapes, and soundscapes, it is critical to remember there is nothing natural about enslavement. This notion extends to the devices used to both organize and naturalize its practice. Utilizing the senses, especially sound, as both a mode and subject of study permits a more complete picture of the conditions of slavery, both in the ability to place ourselves in the physical landscape of enslaved people and to deconstruct social, cultural, and physical systems that have aided in the dehumanization of enslaved people.

____________________

Mya Rose Bailey (they/she) is an Afro-Caribbean scholar interested in multisensory anthropology, temporality, and memory in Black history and culture. They hold a BA in Art History from SUNY New Paltz and are currently completing their MA in Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture from Bard Graduate Center.

____________________

1. Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, “Behind the Scenes: Conservation of Jefferson’s Great Clock,” YouTube, 2021. 5:18–5:31, https://youtu.be/c14pjuikHRs?si=JYXg9x-niaLcgaKv.

2. Karen E. McIlvoy, “Traces of Jefferson’s Time at Poplar Forest,” Poplar Forest Archaeology Blog, April 7, 2017, https://www.poplarforest.org/traces-jeffersons-time-poplar-forest/.

3. Art Historian Wu Hung differentiates between time-keeping and time-telling, noting “[t]ime keeping relies on horology and astronomy that allowed governing bodies to regulate seasons, months, days, and hours,” while “[t]ime telling conveys a standardized conventional time to a large, general public.” Wu Hung, “Monumentality of Time: Giant Clocks, the Drum Tower, the Clock Tower,” Monuments and Memory, Made and Unmade, ed. Robert S. Nelson and Margaret Rose Olin (University of Chicago Press, 2003), 108.

4. McIlvoy, “Traces of Jefferson’s Time at Poplar Forest.”

5. “Servant Bells at Poplar Forest,” Poplar Forest Archaeology Blog, February 4, 2016, https://www.poplarforest.org/servant-bells-at-poplar-forest/.

6. McIlvoy, “Traces of Jefferson’s Time at Poplar Forest.”

7. McIlvoy, “Traces of Jefferson’s Time at Poplar Forest.”

8. Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries, 2006), 139, https://docsouth.unc.edu/southlit/jefferson/jefferson.html.