Folds: Female Sexuality in Artemisia Gentileschi’s Danaë

by Isabella Dobson

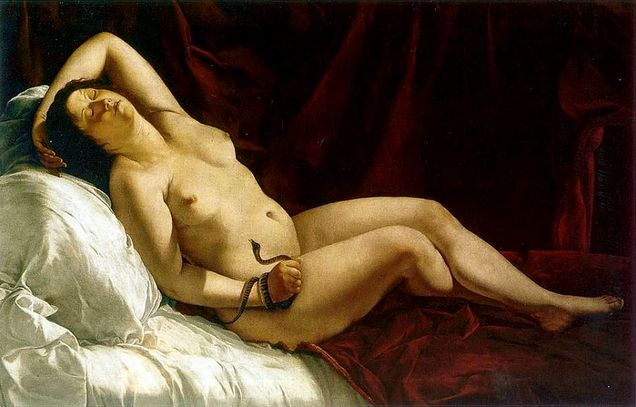

Arched back, clenched fist, lowered eyelids, and rumpled bedclothes: Artemisia Gentileschi’s Danaë depicts the mythological heroine in the throes of sexual pleasure (fig. 1). In the original Greek myth, Danaë is locked away by her father after the Oracle foretells that Danaë will give birth to a son who will kill him. Displeased, the divine Zeus intervenes by impregnating Danaë with a shower of gold that falls into her lap.1 While scholars, such as Mary Garrard, have often interpreted Artemisia’s works in conjunction with the artist’s own rape in 1611, this purely biographic approach makes it impossible to interpret Artemisia’s heroines as anything other than victims or resistors of sexual assault.2 Artemisia’s depictions of biblical and mythological heroines as either particularly ruthless or sympathetic characters are not solely informed by the psychological trauma of her rape; they also record other dimensions of Artemisia’s sexual experience.3 My analysis of Artemisia’s Danaë recenters female sexuality and pleasure as essential considerations in understanding the artist’s oeuvre. Ultimately, Artemisia’s identity as a woman, and her consequent knowledge of female sexuality, explicitly informs how she paints the female body as a site of positive sexual experience.

As a woman who painted women in order to both better understand herself and vie for female excellence, Artemisia was “enfolded” in what she was painting. Cultural theorist and critic Mieke Bal uses this term to mean “embodying…as a way of fully grasping…the self/other dialectic.”4 This enfoldment functions as a double entendre because it points not only to Artemisia’s lived experience as a woman, but also to the folds of cloth that bend around Danaë’s body, consequently showing her as a female form made flesh. Importantly, folds can never exist on their own: an outside force must act on the fabric to produce folds. A fold’s existence makes the fabric a convincing depiction, insisting on the presence of the outside force that creates the folds.5 Moreover, folds are often features of clothing, which, according to fashion theorist Joanne Entwistle, have the added valence of not only constructing social meanings for their wearers, but also making them aware of the outer limits of their bodies.6 The various folds present in Artemisia’s Danaë thus become important sites of visual analysis because they render Danaë’s body as an active participant in pleasure rather than existing as an object of male sexual fantasy.

This seemingly simple act of folding has radical implications for depicting the sexual narrative in Artemisia’s Danaë. Folds reveal to the viewer how Danaë experiences the sensations of her own body. The way Danaë’s body tugs and depresses the folds of bedding beneath her maps the erotic tension that she feels from Zeus’s touch. Art historian Jodi Cranston finds a similar tension in the unveiling of the nude female body in Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus, writing that drapery beneath Venus “appears to have the most intimate relationship with the female body through its mapping out areas of greater and lesser intensity of folds alongside the female form” (fig. 2).7 Since textiles can respond to human manipulation, the cloth’s depressions show that Venus’s body effectively occupies the artificial, painted space she inhabits. In Artemisia’s painting, the fabric most clearly maps the movements of Danaë’s body in the red drapery underneath her buttocks and knees. Bunched underneath Danaë’s bent knee, the rumpled fabric signals that it has been pulled towards her buttocks by her calf to express intense arousal. The fabric that bulges out from underneath the weight of her buttocks likewise marks its sliding progress toward her calf. Additional folds at the end of the bed are tugged by her feet into sharply indented, v-shaped crevices, furthering the impression of Danaë’s erotic response to touch, not to mention their vulvic shape. Inscribed into cloth, this map of tension in Danaë’s lower body inversely mirrors the bridge of tension formed in her chest and back. Pulled taut with the intensity of being touched by the golden coins, Danaë’s body is a site of pent-up tension waiting to be released. Danaë is not just resting on her bed, but rather reaching for and reacting to a feeling of sexual pleasure.

Such a powerful erotic connection between cloth and body not only has ties to a popular conceit during the Renaissance, but is also echoed in a letter written by Artemisia in 1620 to her lover, Francesco Maria Maringhi. During the Renaissance, the belief that objects could be assigned a human-like agency in artistic and literary contexts was reflected in poetry. In a sonnet by Michelangelo, a belt already embraces the waist of his beloved so a lover laments, “What then would my arms do?”8 Thus, Michelangelo suggests that an object can experience human pleasure through the imagined jealous lover. Artemisia uses a similar metaphoric device in a letter to Maringhi dated June 26, 1620, writing that “your Lordship tells me that you know no other woman besides your right hand, envied by me so much, for it possesses that which I cannot possess myself.”9Artemisia’s jealousy of Maringhi’s hand mirrors the envy of Michelangelo’s lover as they both mourn the distance from their respective beloveds.10 Therefore, as evidenced by her adoption of the object-envy metaphor in her letter, Artemisia was intimately aware of the charged associations between inanimate objects and the body, which suggests that she may have been conscious of the drapery she painted beneath Danaë and the way it caresses her nude form.

Danaë’s body as a site of erogenous tension is strengthened by the painting’s relation to another work by Artemisia painted immediately before Danaë: a reclining Cleopatra (fig. 3). The affinity between the poses of the two recumbent women has been noted before by art historian Letizia Treves, especially since they are derivative of the ancient sculpture Sleeping Ariadne.11 Artemisia was likely exposed to this sculpture through prints circulating in seventeenth-century Italy, such as the version created after the Ariadne by Dutch artist Jan de Bisschop , and likely adopted this pose for her Cleopatra (fig. 4). The ambiguity between a female figure swooning or slumbering allows for a variety of psychosomatic states to be grafted onto Ariadne’s pose by the artist. Like Danaë, Cleopatra’s right leg is tucked tightly beneath her left one and her left arm is bent behind her head, giving the impression that the two halves of her body are being stretched in opposite directions. Thus, the aforementioned tautness in Danaë’s body is also present in that of Cleopatra. Resting at the top of her solid thigh, Cleopatra’s right hand also mirrors Danaë, but with an important difference in attributes. While Danaë’s closed fist is studded with fallen gold coins, Cleopatra clutches the instrument of her imminent suicide: an asp. It might seem contradictory for Artemisia to have modeled sexual pleasure and conception after suicide, since the former emphasizes life and the latter takes it. Yet, the two contexts share something in common: both Cleopatra’s and Danaë’s bodies are on the verge of physical transformation. Recognizing this shared corporeal precipice between dying and conceiving, Artemisia ingeniously co-opts how Cleopatra embodies tension to depict the anticipation of Danaë’s erotic experience.

With her gold-showered Danaë, Artemisia asserts that the female body does not have just one erogenous zone but, rather, is covered in them. While the myth dictates that the multitude of gold coins landing on Danaë’s nude flesh represent a male god’s touch, these erotic, haptic moments reveal a network of explicitly female erogenous zones. It is no coincidence that some of the only coins that Artemisia depicts actively touching Danaë’s body have fallen into the crevice formed by her closely pressed thighs so that they are resting as close as possible to her vulva, an area charged with erogeneity, without actually entering it. The only other points of contact between the coins and Danaë’s flesh are in between the fingers of her clenched fist, which are bodily apertures that mimic the double folds of the labia and direct the viewer back to her lap. Even in the falling coins that have not yet touched Danaë’s bare flesh, eroticism is found in the anticipation of their imminent touch as they build a tantalizing erotic tension while suspended mid-air. Every point of contact that a coin makes, or is about to make, with Danaë’s body represents instances of touch that comprise Danaë’s journey toward her sexual climax. Danaë’s tightly pressed thighs and thrown-back head have been cited as evidence for Artemisia’s singular occupation with the difficult aftermath of her rape, but viewing Artemisia’s Danaë through the lens of female sexual pleasure dismantles this limiting, disempowering perspective.12 In its place, a complex network of erogenous zones and pleasurable reactions emerges, which demonstrates that Artemisia defined female sexual experience beyond the psychological trauma of her rape. Under Artemisia’s brush, Danaë is openly ecstatic, lost in her response to stimulating touch.

____________________

Isabella Dobson is a second year PhD student in the History of Art and Architecture at Boston University. She is interested in the ways that eroticism, desire, and sensuality operate in images of the female body from the Early Modern period.

____________________

Footnotes

1. Apollodorus, The Library Vol. I, trans. James George Frazier, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1921) 2.4, 153-155.

2. Mary Garrard, Artemisia Gentileschi: The Image of the Female Hero in Italian Baroque Art (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 204.

3. Scholars have traditionally seen Artemisia’s heroines as uniquely informed by her rape. To give two examples of how Artemisia’s rape is used to interpret her works, Garrard argues that the Pommersfelden Susanna and The Elders by Artemisia depicts an “emotionally distressed young woman” (189) who is “hounded on a psychological level” (198), reflecting Artemisia’s own state of mind, and later argues that Artemisa’s particularly bloody Judith Slaying Holofernes functions, in part, as a vehicle through which “to carry out psychic vengeance against her sexual oppressor” (279).

4. Mieke Bal, Introduction to The Artemisia Files (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2005), xx.

5. Mieke Bal, Quoting Caravaggio (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1999), 30.

6. Joanne Entwistle, “The Dressed Body” in Body Dressing: Dress, Body, Culture (Oxford: Berg Publishing, 2001), 45. Note that Entwistle derives this notion of bodily boundaries from philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty.

7. Jodi Cranston, “The Disordered Bed in The Sleeping Venus,” in Das haptische Bild: Körperhafte Bilderfahrung in der Neuzeit (München: Akademie Verlag, 2013), 35.

8. Cranston, “The Disordered Bed in The Sleeping Venus,” 43-45.

9. Letizia Treves, “Catalogue: A Selection of Letters from Artemisia and her Husband to Francesco Maria Maringhi” in Artemisia (London: National Gallery Company Limited, 2020), 152.

10. Artemisia wishes that her hands were giving Maringhi sexual satisfaction, when instead, her absence has forced him to masturbate on his own. This sexually explicit excerpt from Artemisia’s letter illustrates her sexual agency and desire as a woman.

11. Letizia Treves, “Catalogue,” 121.

12. Letizia Treves, “Catalogue,” 121. While it is unclear which scholars have put forth this opinion, they cite Danaë’s “pulled-back head and firmly pressed legs as signs of resistance” to support a reading of Zeus’s forceful penetration.