Chicana/o/x Spiritual Memories: Layering in the Digital Print Work of Amalia Mesa-Bains

by Gilda Posada

Amalia Mesa-Bains was one of the first Chicana artists to work with digital print. I interpret Mesa-Bains’s printmaking process as a contemporary Chicana/o/x amoxtli, or manuscript. Reading Mesa-Bain’s printworks as an amoxtli that holds sacred memory and knowledge speaks to how Chicana/o/x artists like Mesa-Bains are rebuilding and rewriting the sacred books of knowledge that were burned by the Spanish conquistadores when they arrived in Mexico in 1519. Mesa-Bains’s printworks serve as a pathway for Chicana/o/x Indigeneity to exist in the past, present, and future, but more importantly, they demonstrate how Indigenous-matriarchal ancestral knowledge could be used to heal contemporary Chicana/o/x experiences in a neo-colonial society.

Before European contact with the Americas, the Mexica and surrounding Indigenous peoples in the Central Mexican Valley used pictorial manuscripts, called amoxtli, to document their understandings of the world and themselves. These amoxtli recorded information regarding Mexica ontology, cosmology, and epistemology, relating information on their creation story, history, science, homeland, government, census, tribute, and sacred ceremonies and rituals.1 When the Spanish arrived in Mexico, they quickly learned that amoxtli and the sacred information within were housed in Mexica temples and government buildings. Thus, as part of their conquest, the Spanish burned or destroyed many of these manuscripts. Those that survived the early conquest were later burned by priests or Catholic church officials who saw the information in the codices as evil and in conflict with their conversion aims for the Indigenous peoples. Today, only fifteen known pre-conquest manuscripts survive. However, some early colonial Spanish friars and priests attempted to preserve the aspects of Mexica life captured in burned amoxtli by transcribing oral histories and tasking Mexica scribes with illustrating these manuscripts.2 Over five hundred of these early colonial manuscripts survive, the most famous of which is Bernardino de Sahagún’s work with the Florentine Codex (1577). This essay concerns a lesser-known early colonial codex, the Codex de la Cruz-Badiano (1552), also known by its colonial names, Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis Badianus or the Badianus Manuscript: An Aztec Herbal.3

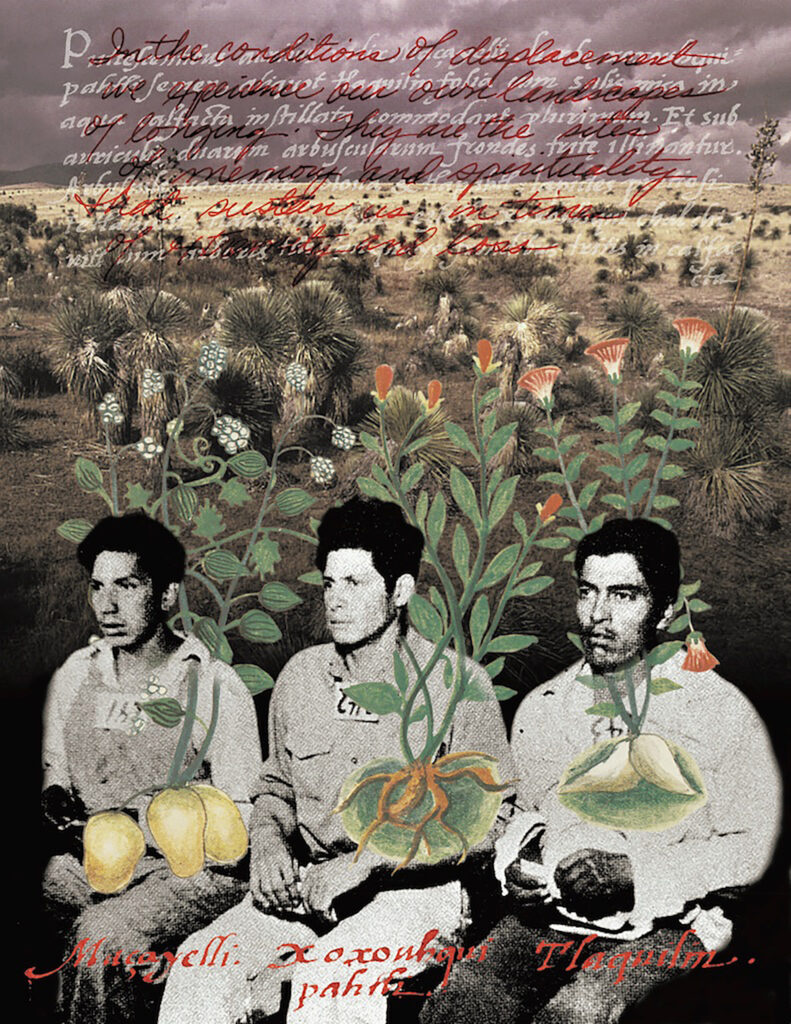

Amalia Mesa-Bains’ work, Badianus Botanicals: Bracero, is from her series Badianus Botanicals, which takes its name from the 1552 Codex. Badianus Botanicals: Bracero is a reclamation and remembrance of the Indigenous medicinal ancestral knowledge found in the Codex de la Cruz-Badiano. By layering imagery of remedies from the codex with contemporary imagery of braceros and the Southwestern United States landscape in her print work, Mesa-Bains offers a map that invites Chicana/o/x peoples to find the fragmented pieces of their body, mind, and spirit that they have lost or forgotten due to colonial violence. Amalia Mesa-Bains states:

To understand the artwork that is inspired by sacred sources it is important to establish the concept of memory. The relationship of memory to history is the connection between the past and the present, the old and the new. For the Chicana/o community there is no absence of memory, rather a memory of absence constructed from the losses endured in the destructive experience of colonialism and its aftermath. This redemptive memory heals the wounds of the past. Memory can be seen as a political strategy in work that reclaims history for the community. In a sense the art making inspired by the remembrances of the dead, the acts of healing and the reflections of the sacred can be seen as a politicizing spirituality.10

Badianus Botanicals: Bracero is a visual politicization of Chicana/o/x Indigenous-spirituality (fig. 1). The central figures in the print are three braceros, who are pictured in black and white. Braceros were Mexican exchange workers who came to the United States as part of the Bracero Program, which was in place from 1942 to 1964. The program contracted 4.5 million Mexicans to take temporary agricultural work in the United States. The Bracero Program had an important effect on the business of farming in the United States, yet braceros faced a significant amount of abuse and exploitation while participating in the program.11 This mistreatment of the Bracero Program laid the foundation for the Chicana/o/x agricultural worker exploitation that took place in the 1960s across the Coachella Valley and Central Valley of California, which would ultimately lead to the creation of the United Farm Workers Union in 1966.12 By centering braceros in her work, Mesa-Bains is recalling the laws, histories, and colonial violence that have been imposed onto the brown Indigenous body. The mostly forgotten Bracero Program was rooted in the commodification and dehumanization of the Indigenous body, whose worth was only measured in terms of its labor.

The invisibility of women in this print is intentional, as many of the braceros’s families were left in Mexico. Today, similar socio-economic hardships and immigration policies continue to be the reasons behind family separation and for the militarization of the United States-Mexico border. Neo-colonial policies such as the North American Free Trade Agreement, drug violence, armed conflict, and corrupt governments in Latin America backed by the United States continue to force the migration of Indigenous peoples from Mexico and Central America toward the United States. Violence, dehumanization, and oppression of the Indigenous body might be more visible when it comes to working conditions, but family separation and continued forced migration practices that cause people to be removed from their ancestral homelands are also forms of continued colonial violence. Indigenous women are often the ones left to carry the consequences, especially when the majority of their husbands migrate to the United States as a means of survival in order to send money back home to their wives and children. In Mesa-Bains’s print, the image of the braceros is in black and white, signaling a collapsing of time between the past and present day, where family separation persists due to neo-colonialism continuing to force migration of Indigenous peoples. The braceros become a marker of time, a proof of existence in this print. The past and present come together to make them the main characters of the story that Mesa-Bains is telling, and there is no erasure of their existence or their humanity in this contemporary amoxtli.

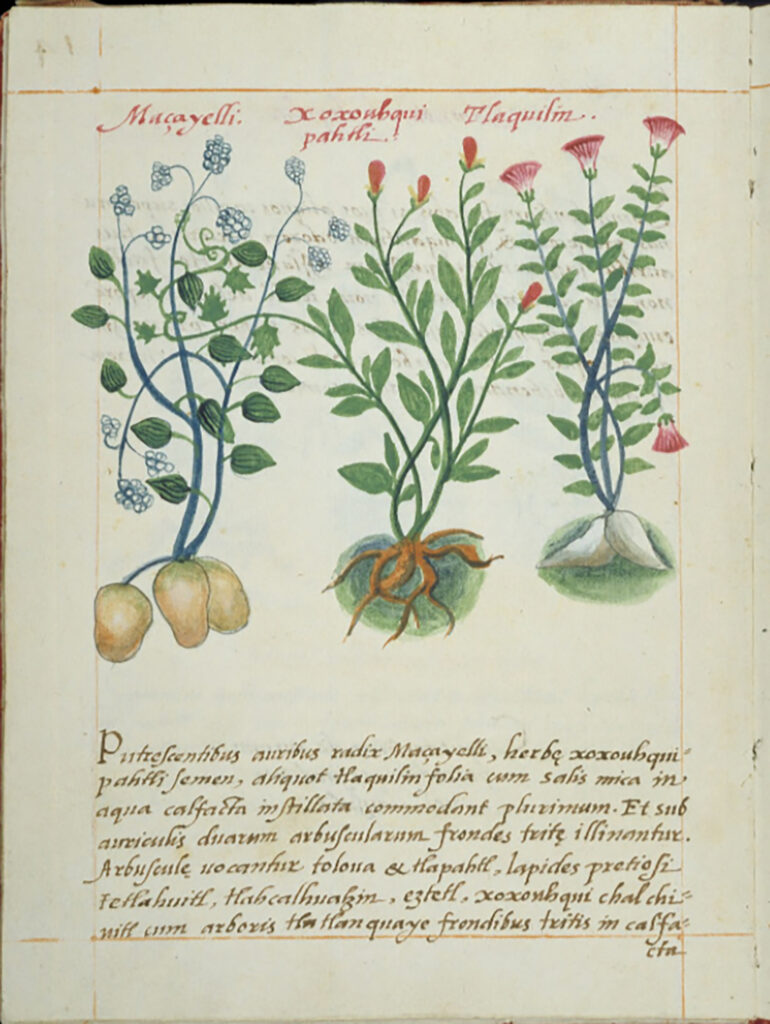

Amalia Mesa-Bains offers a remedy to the pain that her community continues to endure by remembering her Indigenous-ancestral healing practices in the form of images from the Codex de la Cruz-Badiano. Specifically, she references images from Plate 22 , which depicts three different medicines, each of which are laid over a different bracero (fig. 2). They are macayelli, xoxouhquipahtli seeds, and tlaquilin leaves, which, when combined, provide medicine for ear pain. This information is written in Latin under the drawing of the herbs on Plate 22, with detailed instructions for their preparation and use.13

In her print, Amalia Mesa-Bains keeps the Latin portion of the original manuscript but relocates the text to the top of the print. Additionally, she changes the color of the ink in which it is written. Instead of the original brown ink, Mesa-Bains uses a transparent white ink that fades into the background of the print. This white color directly connects to the bracero figures. When seen together, the two become one, implying that Mesa-Bains is creating a link between two different moments in time. There are several ways to interpret their unity. The first is that Mesa-Bains is offering medicine to the braceros who are in pain, the second is that she is offering them healing for their exploitation and dehumanization at the hands of colonial powers. A third interpretation is that she is offering medicine to American citizens who have fallen deaf to the cries of these neo-colonial victims, medicine for them to open their ears and bear witness—if not act—to the cries of those who are in pain due to their exploited labor in both the past and present.

The use of Latin points to the ongoing violent histories of European colonialism in Mesoamerica. Mesa-Bains visualizes the blood and destruction that the Catholic church has on their hands by deploying the language used to justify violence and forced assimilation for Chicana/o/x peoples. Elsewhere, she uses Nahuatl in her print to honor the Indigenous medicine and her ancestral connection to Indigenous knowledge. The tension of being caught between worlds can be seen in the text overlayed on the remedy instructions. In red font Mesa-Bains writes, “In the condition of displacement we experience our own landscape of longing. They are the sites of memory and spirituality that sustain us in times of extremity and loss.” She is acknowledging the losses caused by displacement and the transformation of Indigenous peoples into proletarianized subjects on the settler-colonial stage. At the same time, she points to the resilience and endurance of Indigenous peoples despite colonial destruction. Mesa-Bains is calling ancestral memory and spirits who have walked on this land to be the primary tool for Chicana/o/x peoples to survive. However, it is that same spirit that needs the medicine to heal and continue to endure.

The remedy that Mesa-Bains chose for this print is one which is vital to cure as soon as the illness begins because it can cause susto or loss of tonalli.14 According to Mexica belief, tonalli, or life-force, lives in the head.15 An individual can slowly lose their tonalli and eventually perish through susto, or spiritual fright, that enters the body through their mouth, ears, or eyes.16 The remedy that Mesa-Bains brings forward is categorized as a cure for remedying the tonalli due to a sickness in the ears, one that must be applied quickly. Mesa-Bains is directing the viewer’s attention to the sense of hearing and listening especially as it relates to susto and the “memory of absence.”17 By visually layering painful Chicana/o/x histories, imagery of colonialism, and the physical exploitation of Chicana/o/x peoples, Mesa-Bains is reminding the viewer that the memory of colonialism is not lost, but rather that to change the condition of the present and future, one must heal the trauma or susto that has been inflicted onto the Indigenous body throughout centuries of violence. She is providing relief to the ears and restoration of spirit or tonalli for those that live with pain due to the physical, mental, and spiritual exploitation they face. However, it is important to note that the remedy selected by Mesa-Bains is one that requires daily treatment and calls for all aspects of a plant’s life cycle to be used: seeds, leaves, bushes, and roots. It also requires that the plants be taken through various transformations before they can be used as a cure, such as cutting, boiling, grinding, and rubbing. With this, Mesa-Bains is signaling that healing and restoring the tonalli will not be easy and that it will be a long and hard process. She is pointing to the importance of listening to past experiences so that future Chicanas/os/xs will not forget and instead learn from the experiences, memories, and spirits of their ancestors.

In Badianus Botanicals: Bracero, the landscape also reveals one last important layer to the Chicana/o/x experience: that of mother earth, who gave birth to Chicana/o/x-Indigenous ancestors. The landscape in this print is from a United States-Mexico border crossing desert region, identifiable by the topography and flora depicted in the background. The cacti are reminiscent of the creation story of the Mexica, who spent hundreds of years on a journey across the United States Southwest and Northern Mexico desert regions being guided by Huitzilopochtli to the place where they would establish their homelands.18 By including the Southwest desert, Mesa-Bains is not only reminding Chicanas/os/xs of their Indigenous ancestry tied to a place and time, but also the contemporary pains caused by the displacement of Indigenous peoples from their homelands across the global South. Badianus Botanicals: Bracero is an amoxtli and pictorial reminder that the relationship between humans and land is the medicine that will keep the Chicana/o/x spirit and peoples moving forward despite the hardships that they continue to face.

____________________

Gilda Posada is a Xicana art historian, artist, and curator from Southeast Los Angeles. She received her AB from UC Davis and her MFA and MA in Visual and Critical Studies from California College of the Arts. Currently, Gilda is a PhD candidate in History of Art at Cornell University.

____________________

1. Elizabeth H. Boone, “Central Mexican Pictorials,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican Cultures, ed. Davíd Carrasco (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 155-158.

2. María Elena Briseno, “Códices: Los antiguos libros del nuevo mundo,” in Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas 24, no. 81 (Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México 2002): 175-178. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0185-12762002000200008&lng=es&nrm=iso.

3. The Codex de la Cruz-Badiano is known by several names such as: Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis Badianus, Badianus Manuscript, and Codex Barberini.

4. “The Badianus Manuscript,” World Research Foundation. http://www.wrf.org/ancient-medicine/badianus-manuscript-americas-earliest-medical-book.php.

5. EC Del Pozo, “Prefacio,” in Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis, by Martín De la Cruz, trans. Juan Badiano (Mexico City: Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, 1964).

6. Andrés Aranda et a,. “La materia medica en el Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis,” Revista de la Facultad de Medicina 46, no. 1 (2003): 13. https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/facmed/un-2003/un031d.pdf.

7. The sequence of the remedies starts with the head and ends at the feet, signaling some correspondence to the thirteen upper worlds, and seven underworlds that the Mexica believed ruled all forces and beings.

8. Carlos Viesca T. and Andrés Aranda, “Las Alteraciones del Sueño en el Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis,” Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl 26 (December 27, 1996): 156.

9. Carlos Jair García-Guerrero and Feliciano Blanco-Dávila, “La cirugía plástica y el Códice De La Cruz-Badiano,” Revista Medicina Universitaria 6, no. 22 (2004): 52.

10. Amalia Mesa-Bains, “Spiritual Visions in Contemporary Art,” in Imagenes E Historia/Images and Histories: Chicana Altar-Inspired Art, eds. Constance Cortez and Amalia Mesa-Bains (Medford, MA: Tufts University, 2000), 2.

11. “Opportunity or Exploitation: The Bracero Program,” The National Museum of American History. http://amhistory.si.edu/onthemove/themes/story_51_5.html.

12. From 1953-1954 concerns were raised across states that held a large bracero presence, such as Texas and California. The concerns were due to assimilation resistance coming from bracero and Mexican immigrants, along with the large number of border crossings occurring during an economic decline in the United States. Additionally, the end of the Bracero Program on December 31, 1964 set the baseline for many other immigration policies in the United States, such as Operation Wetback, Operation Gatekeeper, and the formation of the United States Immigration and Naturalization Service.

13. Translation from William Gates 1939 publication: Festering in the ears will be helped the most by instilling the root of the maza-yelli, seeds of xoxouhqui-patli plant, some leaves of the tlaquilin with a grain of salt in hot water. Also the leaves of two bushes, rubbed up, are to be smeared below the ears; these bushes are called tolova and tlapatl; also the precious stones tetlahuitl, tlacahuatzin, eztetl, xoxouhqui chalchihuitl, with the leaves of the tlatanquaye tree macerated in hot water, ground together and put in the stopped up ears, will open them.

14. Aranda et al., “La materia medica en el Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis,” 17.

15. Maarten Jansen and Gabina Aurora Pérez Jiménez, “Time and the Ancestors,” in The Early Americas: History and Culture, eds. Corinne L. Hofman and Maarten E.R.G.N. Jansen Vol. 5 (Boston, MA: Brill, 2017), 18-19.

16. Teresa Cupryn, “La expresión cósmica de la danza azteca,” Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales 37, no. 147 (1992): 45.

17. Mesa-Bains, “Spiritual Visions in Contemporary Art,” 2.

18. Patricia Chicueyi-Coatl Juarez, “How to Read Amoxtin,” Online Workshop UC Gill Tract Community Farm. Albany, California, May 23, 2020.