news

Editors’ Introduction

by İkbal Dursunoğlu

This issue of SEQUITUR reflects upon the “Interiors” of our architectural and psychological boundaries, and witnesses how the overlap of these physical and mental spaces creates both shelters of intimacy and sites of estrangement. Despite writing on one of the most durable, and yet most flexible, features of human existence, and around diverse temporalities from antiquity to the present and covering a global scope, there is a remarkable thematic consistency to the explorations of our authors. Subjectivity and access emerge as the two central sub-themes of this issue, which perhaps tells us as much about our current shared condition as it does about the specific subject matters covered.

Human subjectivity and indoor space appear mutually constitutive of each other, at present as in the past. But this subjectivity is always contingent upon the level of access and control that one has to a space, to its knowledge, to its resources, and to the world external to it. The examinations presented here, of varying configurations of access and denial in diverse temporal and cultural contexts, provide incredibly rich glimpses of the myriad ways in which our relationships to interior space have taken shape. Sometimes human subjectivity has organically developed in tandem with indoor space and, while designing it, we also gave form to our own selves. At other times, a discovery of space parallel to our existence has thrown new light on and changed the ways in which we defined our identity. And at yet other times, we have had to build subjectivity against the restrictions imposed in the spaces we have inhabited.

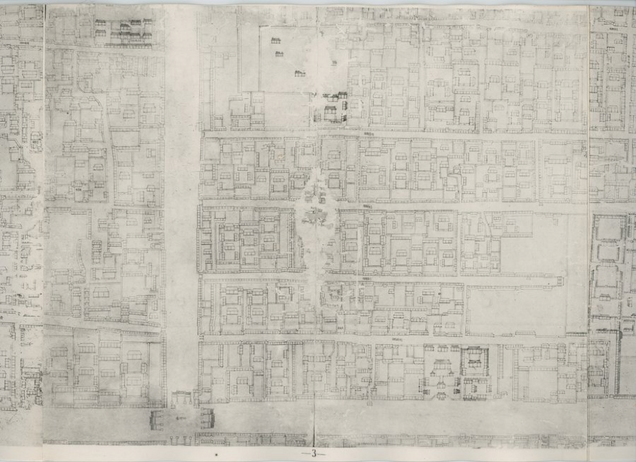

In a fascinatingly varied array of feature essays, these questions are explored in full range and nuance. Rachel Bonner situates the eighteenth-century portrait of Ramona Antonia Musitú y Valvide Icazbalceta by Juan de Sáenz in the broader tradition of New Spanish representations of the American territories. She radically analyzes Musitú’s portrait through politics of racially defined land-ownership, arguing that the portrait both lent and denied agency to its sitter at the same time. In her thoughtful contemplation of Edward Krasiński’s employment of a blue Scotch Tape to circumscribe the walls of his Warsaw studio apartment in the 1970s, Nadia Gribkova contends that while this gesture placed the artist within a larger twentieth-century avant-garde abstract art movement, his positionality as the citizen of a post-Stalinist country was reflected in a hesitation to participate in an all-encompassing, exhaustive universalism. In a truly interdisciplinary study, Katie Ligmond traces the formal and intellectual links between Wari urban and tomb layouts and Inka textiles. In doing so, she reveals that the adoption of similar grid structures, which the Inka possibly inherited from the Wari, point to analogous patterns of obfuscation and control. In both societies, the elites had seemingly exclusive access to the logic underlying these patterns at the expense of the commoners, indicating the parallel mechanisms of imperial power they employed. Tyler Rockey presents a richly textured account of the Renaissance discovery of an ancient Roman palatial ruin, and the subsequent artistic recreation of this space in the Logetta of Cardinal Bibbiena in the Vatican. Rockey interprets this transposition within the context of humanist endeavors to revive the city of ancient Rome in the sixteenth-century present, and argues that, by this gesture, the Logetta and its ancient source became heterotopic spaces where multiple temporalities collided and accustomed norms were altered.

The research spotlights featured in this issue offer notes on exciting work in progress on completely different subjects that nevertheless resonate well with each other. Mew Lingjun Jiang present their preliminary findings on a portable bodhisattva shrine, currently located in Sannohe, Aomori, Japan, dedicated to the Deity of Gambling and covered with Portuguese-inspired playing cards. Jiang’s report reflects on how the cult of this deity bridges the seventeenth century to our day through continuous practice, and a remote rural Japanese town to the rest of the nation even during the pandemic. In their research spotlight, Amelie Ochs and Rosanna Umbach analyze how postwar German lifestyle and home-decoration magazines participate in the formation of modern national subjectivities by shaping notions of the ideal dwelling, and, by extension, the ideal citizen, via strategic employment of design elements such as layout, imagery, and typography.

Both of the book reviews featured in this issue reflect on the ways that art offers strategies of resistance to repression under restrictive environments. María de Lourdes Mariño reviews two independent art catalogues, Iter Criminis and El Parque Horizontal, curated by Isel Arango and Anamely Ramos respectively. Both of these catalogues grew from a Cuban alternative cultural movement that seeks to create and maintain art spaces independent from central state institutions of culture, radically claiming the private space of the home as a site of underground artistic gatherings in the face of criminalization by the state. Michael Rangel reviews Nicole Fleetwood’s Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, focusing on artists imprisoned by the United States prison system, heavily biased along racial and class lines. Fleetwood identifies a carceral aesthetics, emerging from within the prison system, which brings both “invisibility and hyper-visibility to those incarcerated and their art,” to quote Rangel.

Against this grim landscape, the exhibition reviews in this issue offer brighter prospects, though perhaps only to those of us who are able to enjoy them. Shannon Bewley examines Jessica Burko’s exhibition at Shelter in Place Gallery, Boston—a gallery space creatively designed to enable local artists to reach their audiences even under quarantine conditions through social media. In her tiny exhibition of found furniture and photographic material, Burko explores the ramifications of a socially distanced life wherein the home space is discovered anew. Alice Quaresma’s exhibition at HOME, displayed at Pablo’s Birthday in New York City and also online, presents a much warmer view of the home, as described by Josephine English Cook. Through a series of photographic mixed-media works, the artist ruminates over displacement, restrictions on travel, and the intimacy of feeling at home.

The image of interiors that rises from this collection of writings might be imagined as reminiscent of the illustration that accompanies this introduction. In the scene, Alexander the Great of the Persian tradition visits the court of Nushaba, the Queen of Barda’, in disguise; yet the latter wisely succeeds in identifying him from his portrait. After a long conversation followed by convivial feasting, Alexander leaves the court, which he had visited to spy, as a more enlightened man. The painting captures the moment of recognition: under the spy’s nervously watching eyes, Nushaba gracefully points at his portrait. This resonates with the essays presented here, where our authors observe that human subjectivity often takes form in interior space through the agency of art. In the illustration, the restricted space of the court serves as the stage where Alexander’s identity is discovered and his personality subsequently reshaped—humbled but bettered—in this elegant conversation around a painting. The rarified nature of the gathering ensures that Nushaba’s knowledge is available only to a select few.

Thus, issues of access, like those that haunt the accounts of our authors, demarcate the levels of this painting and define the reach of its figures. The gathering takes place exclusively behind the shut gates of a castle beyond unreachable mountains, but in open air, in a courtyard that connects to the garden that we see on the right. As the host, Nushaba is seated on a dais in an iwan, a rectangular vaulted hall walled on three sides, with one side entirely open to the outside. This central space of authority is inaccessible to any other figure in the painting. Movement through the doors to different spaces of the palatial complex is possible, but highly regulated. Inside the folds of the complex, seen in the upper parts of the illustration, various figures perform their duties or direct their gazes downwards from above at the happenings of the court, their view not as readily available from below, with a distance both endowing and denying them access to knowledge at the same time.

We hope that this issue of SEQUITUR performs as a welcoming virtual space of interiority with open access to knowledge and inspiration, helping to build positive agency and empowerment in the never-ending process of selfhood construction.

Wohnseiten: The Interior(s) of Home Journals

by Rosanna Umbach and Amelie Ochs

Initiated by Irene Nierhaus and Kathrin Heinz in 2015, Wohnseiten is a research project based at the Mariann Steegmann Institute Art & Gender in cooperation with the University of Bremen, Germany. It has been developed in the Institute’s main research field wohnen+/-ausstellen (“dwelling+/-exhibiting”), which addresses the visualization of the concepts of dwelling and exhibiting in their interlinked discourses. This research field analyzes dwelling as a concept and process of residence, as well as practices of living and exhibiting as part of complex display strategies.

Wohnseiten examines home journals spanning from the nineteenth century to the present in order to analyze their serial, didactic aesthetics.1 The project contends with the following questions: How does the magazine, as a format, produce discourses on dwelling and, thus, living? To what extent does the interplay of text and image mediate, formulate, or design specific forms of subjectivation? The aesthetic structure of the lifestyle magazines reveals power constellations through which occupants and readers are addressed as socially and politically active, gendered, and consuming subjects. The magazine’s instructional content on how to dwell "properly" has gradually established dwelling as a social and aesthetic practice.2 Normalized images of dwelling have been developed through their repeated visualization in home magazines, shaping hegemonic ideas of space and occupants. Thus, magazines form intertwined “displays” that are linked to specific socio-political discourses correlating to their period of publication.3

Our field report aims to contribute to the existing scholarship on interiors and types of dwellings by bringing new focus to the interiors of home journals as socially-constructed spaces. Relying on the findings of our research, we locate the home journal in the center of a media-based discourse on dwelling/living.4 In the following, we demonstrate how display strategies function as didactic instructions, from a postwar picture book to current social media interfaces.

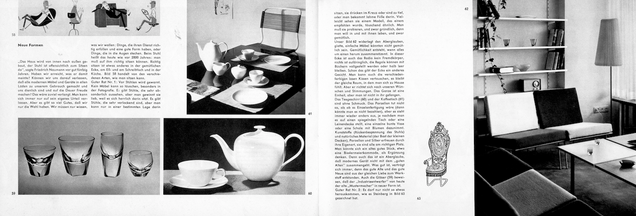

Figure 1 shows a double-page spread taken from a Bilderbuch (“picture book”) published by the Deutscher Werkbund in 1958.5 A photograph of a mid-century living-room interior, which fills half of the right-hand page, catches the viewer’s gaze. Next to the photograph, a caricatured drawing of an anachronistic piece of furniture—half historicist arm chair, half modernist tubular steel chair—is depicted in small scale. On the left-hand page, three photographs of glassware and tea sets alongside another small-scale drawing, showing four types of chairs in order to exaggerate the depiction of different types of seating, stand out from the type area. The meaning of the bold title, Neue Formen (“New Forms”), is explained by the accompanying text. Emphasizing modesty and simplicity, it describes only the merits of these new forms, represented by the “plain” glassware, tea sets, and living room furniture in the photographs. In contrast to these qualities, the text says that furniture like the armchair in the caricature should be avoided. The reason for this refusal is not mentioned; it is left to the reader’s imagination, which is trained by the picture book’s selection of images. Through numerous examples and using a rhetoric that highlights reduced modernist designs, the picture book teaches the viewer/reader to reject ornate forms. Thus, what is formulated here is not only advice about how a living room should be furnished, but also norms of living. This conclusion is supported not only by the hierarchy of the photographs over the drawings, but also by the whole arrangement of the type area.6

The previous example draws on a tradition of manuals for how to design the domestic interior (Wohnratgeber), which frequently appeared in various forms in the first half of the twentieth century. After the Second World War, the picture book introduced a new order of reality to a generation of young citizens within the Federal Republic of Germany. For this purpose, the picture book takes up the modernist (visual) rhetoric by confronting old and new designs from everyday life. The manuals’ didactic narratives were not only taken up by the picture book, but also by home journals like Schöner Wohnen (“More Beautiful Living”).

In 1965, Schöner Wohnen depicted the "agile" life of the Wallner family in the report titled “Wir Lieben Es, Mobil zu Wohnen” (“We Love Living Mobile”) (fig. 2). Mobile living is introduced as an “unusual program” of living, which consists of versatile and portable furniture that can adapt to the occupants’ needs and that correlates to a certain modernist idea of a flexible way of life.7 The first double-page spread consists mostly of square-format photographs, arranged as modules, surrounding narrow text columns. It seems as if the ideals of mobile living and flexible interiors are conceptually translated in the layout’s style: Not only does the aesthetic structure (in this example: the arrangement of images and typography) proclaim the idea of mobile living, but the images themselves also do so. One photograph shows a child in a home library reading a magazine that is propped up by a pillow. The child sits on a wooden bench—a piece of portable furniture that creates a temporary Leselandschaft (reading landscape). The magazine spread’s seven images, including this one, produce a narrative where the subject should be just as flexible as the interior itself. Mobile dwelling is presented as a “recipe worth copying” that needs to be learned, and Schöner Wohnen educates its readers/viewers by providing supposedly authentic examples of how to create a modern interior and, thus, how to become a modern citizen.8

In the twenty-first century, ideas of "proper" dwelling are (re-)presented in IKEA catalogs, in television series, on Instagram, and in blogs. The lifestyle magazine tries to incorporate social media into its narrative and aesthetic structure.9 Living at Home + Holly, for example, is labeled as Europe’s first influencer magazine for interiors. It is curated by blogger Holly Becker, an American expat from Boston now living and working in Hannover, Germany.10 Some of the magazine’s pages imitate layouts used in social media, thus linking the printed page to the visual grid of Instagram. The magazine’s social media account, in addition to other interior blogs, is shaping representations of home and interior aesthetics, taking up didactic display strategies as the Schöner Wohnen did in the 1960s. Today, the "readers" can also be part of the (visual) narrative by responding directly through comments or by using the same hashtags to link their own posted Instagram photographs to a certain discursive archive.11 Pictures posted on social media give insight into ostensibly "authentic" but often carefully-arranged interiors; we do not see dust bunnies, dirty dishes next to the bed, or the actions of homemaking in the pictures. Instead, we see well-composed arrangements and fragmented close-ups of furniture. The pictures are subtitled with a multitude of hashtags indicating that the viewer is facing "#scandistyle" or "#coziness." They collectively serve as yet another translation of internalized visual patterns that demand that the subject exhibit images of their home and reproduce ideas of the "right" way to dwell.

Within the research group Wohnseiten, which focuses on magazines, journals, and media networks, we call attention to specific display strategies and discuss their implications for society. We address magazines as central elements of the (re-)production of Wohnwissen (“knowledge about dwelling”), or a reflection of social conditions and ideals, historically disseminated through various media.12 Through the given examples, we have tried to show how visual elements like images; typography; graphics and illustrations; and floor plans and diagrams design a specific idea of dwelling. The picture book teaches the viewer/reader to compare images in order to make out the differences between the depicted designs: while the double-page spread is the tableau for comparative visual analysis, the ideologically-organized interplay of text and image is the foundation of the viewer’s aesthetic judgement. The latter is the book’s objective.

In the display of Schöner Wohnen, magazine images and texts are interlinked to form a discursive aesthetic structure that instructs readers by showing them ostensibly "authentic" examples of furnishing and living in a "modern" home. Living at Home + Holly demonstrates how digital discourses and interfaces are integrated into the aesthetic structure of the magazine, connecting different types of media in its display. What is more, these didactic implications are even more pronounced and interactive when social media becomes a platform where former readers transform the internalized ideas of the "right" way to dwell by exhibiting their own homes using the same aesthetic imagery and display strategies as those found in home journals.

Wohnseiten aims to connect to other institutions and researchers working on the topic of the home journals’ interior(s), aesthetic structures and social implications. Following the success of our first conference on the topic in 2019,we are currently establishing an early career researchers’ colloquium series.13

____________________

Rosanna Umbach

Rosanna Umbach studied Art – Media – Aesthetic Education and Cultural Studies, Art and Cultural Mediation at the University Bremen. Her dissertation project Un/Gewohnte Beziehungsweisen examines family concepts depicted in the display of Schöner Wohnen magazine (1960–1970). Since 2017 she is holder of the Mariann-Steegmann-Scholarship.

Amelie Ochs

Amelie Ochs studied Art and Visual History, History and Humanities in Berlin, Paris, and Dresden. Since 2019 she has worked as a research assistant at the University of Bremen / Mariann Steegmann Institute Art & Gender. Her dissertation examines the context of image consumption and display strategies in early 20th century still life photography.

____________________

Footnotes

1. The project’s full title is “Lifestyle Pages – German language home journals from the nineteenth century to the present and their dissemination as media.” Although the English translation describes its objective very well, we would like to stick to the German term Wohnseiten. This term contains the noun “Wohnen” which indicates both the practice of living (at home) and the home’s condition (respectively dwelling/housing). The compound "Wohnseiten" indicates both: the pages of the lifestyle magazine and the different possibilities ("sides") of living. For further information on the project, see https://mariann-steegmann-institut.de/forschungsprofil/.

2. Research on this topic is relatively new and mainly located in the fields of design studies, architecture, and art history. Our focus on the (modern) magazine as a format that offers important insights into the discourse on dwelling was influenced by Jeremy Aynsley. See Jeremy Aynsely and Francesca Berry, "Publishing the Modern Home: Magazines and the Domestic-Interior 1870‒1965," Journal of Design History 18, no. 1 (2005): 1–5, https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/epi001. See also Jeremy Aynsley, and Kate Forde, eds., Design and the Modern Magazine (Manchester, UK: University Press, 2007).

3. Irene Nierhaus, "Seiten des Wohnens – Wohnzeitschriften und ihr medialer und gesellschaftspolitischer Display," in FKW//Zeitschrift für Geschlechterforschung und Visuelle Kultur, no. 64 (Seitenweise Wohnen. Mediale Einschreibungen, ed. Katharina Eck, Kathrin Heinz, and Irene Nierhaus, 2018), 18–28.

4. See Irene Nierhaus, Kathrin Heinz, and Rosanna Umbach, eds., WohnSeiten. Visuelle Konstruktionen des Wohnens in Zeitschriften (Schriftenreihe wohnen+/-ausstellen, Bielefeld, Germany: Transcript, 2021).

5. Clara Menck’s Ein Bilderbuch des Deutschen Werkbundes für junge Leute (Düsseldorf: Rotations-Kupfertiefdruck L. Schwann, n.d. [1958]) is a 30-page leaflet rather than a picture book. It was addressed to 14- to 20-year-olds, and intended as an introduction to good form.

6. The magazine’s materiality stands out due to various forms of images and text fragments, arranged on bundled pages. Text, photography, and drawings relate to each other in the ways they are placed in the type area. In our research, mainly two theoretical concepts help us to approach the designed (double) page: Dagmar Venohr’s term "iconotext" and Sybille Krämer’s concept of Schriftbildlichkeit ("the script’s/page’s figurativeness"). The latter consists of four aspects: (1) The aspect of structure, i.e. the standing of a statement or an image on the designed page; (2) the visible and the invisible; (3) the production and revocation of meaning; and (4) the text’s anti-hermeneutic dimension which makes interpretation easier. See Sybille Krämer, “‘Schriftbildlichkeit’ oder: Über eine (fast) vergessene Dimension der Schrift,” in Bild – Schrift – Zahl, eds. Sybille Krämer and Horst Bredekamp (München: Wilhelm Fink, 2008), 157–76. Dagmar Venohr describes the magazine’s aesthetic structure as an “iconotextual COMPOSITION.” The use of color, typography, and graphic(s), as well as the visual correspondences and contrasts produced by them, must be analyzed in order to decipher the magazine’s “iconotextual NARRATION,” Dagmar Venohr, medium macht mode. Zur Ikonotextualität der Modezeitschrift (Bielefeld, Germany: Transcript, 2010), 113f (emphasis in original).

7. “Wir lieben es, mobil zu wohnen,” Schöner Wohnen 6, no. 10 (1965): 38–9.

8. Ibid.

9. In the second episode of their radio show Wohnfrequenz – Zuhörgespräche über Wohnbilder, Anna-Katharina Riedel, and Rosanna Umbach discuss the issue 1/2020 of Living at Home + Holly and how layout, strategies of (re-)presentation, and aesthetic structures of both print and social media are interlinked in its display. See https://sphere-radio.net.

10. The first issue was published in 2019. The magazine is read by German-speaking countries in Europe, but it has an English language version on ePapers.

11. Schöner Wohnen as a thematic archive is discussed in Anna-Katharina Riedel, “Präsentationsfläche Tisch. Angeleitetes Anordnen in Serie auf den Titelblättern der Schöner Wohnen zwischen 1980–1999,” in WohnSeiten: Visuelle Konstruktionen des Wohnens in Zeitschriften, eds. Irene Nierhaus, Kathrin Heinz, and Rosanna Umbach (Schriftenreihe wohnen+/-ausstellen, Bielefeld, Germany: Transcript, 2021).

12. Irene Nierhaus and Andreas Nierhaus, “Wohnen Zeigen. Schau_Plätze des Wohnwissens,” in Wohnen Zeigen. Modelle und Akteure des Wohnens in Architektur und visueller Kultur (Schriftenreihe wohnen+/-ausstellen, Bielefeld, Germany: Transcript, 2014), 9–35.

13. See the documentation in the volume WohnSeiten, cf. footnote 4.

Between Spaces: The Domus Aurea, the Vatican Loggetta, and Foucault’s Heterotopia

by Tyler Rockey

The Renaissance artists and antiquarians who descended into the earth and into the ruins of the Domus Aurea, the palace of the first-century Roman emperor Nero, found themselves in a strange space where their present was collapsed with the ancient Roman past and surrounding them was fantastical and bizarre painted decoration. This rediscovery in the late 1400s of an ancient Roman structure, with extant examples of grotesque painting, expanded and spurred interest in this style and technique of decoration. Quickly, it became a pronounced and ubiquitous feature of Renaissance interior spaces.1 Rather than trace the development and diffusion of this decorative mode or stylistic exercises of fantasia, I would like to present a way of thinking, informed by Michel Foucault’s work, about space itself and about the complex relationships between spaces, as negotiated through the artistic practice of imitation and the Renaissance archaeological imagination.2

The Loggetta of Cardinal Bibbiena in the Vatican (fig. 1), a narrow, vaulted space covered in grotesque decorations designed by the famed Renaissance artist Raphael and his workshop around 1516, provides an intriguing case study due to its mirroring of the form and decoration of the Domus Aurea’s similarly long, vaulted hallway, known as the cryptoporticus (fig. 2). At the time of its discovery, this subterranean ruin had become an example of what Foucault describes as a “heterotopia,” a “different place” at variance with the norms of time and reality.3 The translation and transposition of this space into the Vatican is not, however, a simple anachronism or copy of this heterotopic place. It is a physical product of the Renaissance task of imagining a re-completed and living antiquity, realized through art.

Foucault’s concept of heterotopia seeks to define different spaces in relation to broader cultural norms and social functions. This model assumes that the spaces we inhabit are laden with “bundles of relations” that both demarcate them as discrete and localizable as well as tie them together through proximal connections.4 In this way, space is organized in a manner that makes sense. But within this model there are certain spaces at variance with other sites; these spaces neutralize or reverse these relations with other spaces because they are utterly different. They are heterotopias, or different places.5 They can contain a sense of the uncanny, where time and space are different, where people are expected to behave differently, or where multiple spaces are juxtaposed into one, such as in cemeteries, theaters, or museums.6

The underground ruins of the Domus Aurea can be read as such a location. It exists alongside the history of the city of Rome, yet is locked within a different archaeological stratum. In effect, it is both present and distant, both familiar and alien. An anonymous fifteenth-century artist who visited this place poetically described this experience of difference and the oddities of being there: “[I]n every season the rooms are full of painters. Here summer seems cooler than winter . . . we crawl along the ground on our stomachs, armed with bread, ham, fruits and wine, looking more bizarre than the grotesques.”7 For the Renaissance visitors, the Domus Aurea was a place where time was confused. Here the present and past collided in new temporal-spatial connections and fantastical decoration charged this space with a strangeness that the visitors saw in themselves.

Furthermore, this type of decoration was the antithesis of what the Renaissance had understood as classical and sought to implement through its antique vocabulary. Grotesque decoration, derived from ancient Roman precedents, was employed in fresco or sculpted on walls, ceilings, and architectural frames. It was characterized by hybrids of plant, animal, and human forms; metamorphic and sprawling ornamental candelabra motifs; and illogical and irrational compositions. All of these are noticeable in an anonymous sixteenth-century French artist’s drawings from the cryptoporticus (figs. 3, 4).8 In essence, for the Renaissance viewers, the grotesque presented an inversion of the classical aesthetic ideals of naturalism, harmony, proportion, and rationality of form. And yet this antithesis emerged from the Roman earth and directly out of the classical past, greatly shifting attitudes around this decorative mode through the significance of the discovery of the ruin.9

In the early Renaissance, prior to the finding of the Domus Aurea and before other archaeological projects of exhumation, the work of reconstructing ancient spaces was less architectural. Rather, this reconstruction occurred within the mind and was transmitted through writing and poetry. To Petrarch and his scholarly contemporaries in the mid-fourteenth century, classical truth was indeed buried in deep, inaccessible caverns. Thus, any restoration ought to rely on imagination and literary invention.10 Reading and writing, in fourteenth- and early fifteenth-century humanist philological practices, were the keys to a Roman resurrection—not as a physical location but as an idealized and re-completed mental form based on the contemplation of the material remains.11

However, the work of subsequent fifteenth-century humanists laid the groundwork for a shift from imagination to outward reality. In his work Roma Triumphans of 1459, Flavio Biondo presented a literary construction arguing for a unity of authority between Rome’s pagan and Christian histories.12 This was a mode of thought by which the Roman past would become more clearly part of a contemporary Christian reality through the juxtaposition of the ancient city and early modern theology. Thus, new vigor and expanded license would be added to the project of resurrection that shifted from humanist fiction to a reality mediated by the visual arts and the curation of spaces. The figurative culmination of this project was the letter of Baldassare Castiglione and Raphael to Pope Leo X, written around 1519, where the humanist-diplomat and the artist describe their work of restoring and fleshing out the “lacerated corpse” of Rome as the obligation of the moderns.13 Sixteenth-century artists went beyond the humanist literary imagination, which had conjured a vision of both present and past engendered by the study of ancient materials, and worked instead directly into the physical urban fabric in order to resurrect the body of ancient Rome.

This is what we see in the Loggetta of Cardinal Bibbiena, a space constructed by Raphael14 and decorated by the grotesque specialist of his workshop, Giovanni da Udine.15 Raphael and Giovanni had descended into the heterotopic Domus Aurea sometime around 1510, reemerging with the imagined and idealized mental forms of the spaces they encountered, and transformed these concepts into tangible forms in the current time and space of the Vatican.16 The shape of the Loggetta clearly recalls that of the cryptoporticus and the ethos of the former’s decorations are inspired by the latter’s ceilings and walls in a manner that most closely imitated the original space to date.17 Thin garlands hang between delicate architectural forms, birds and animals perch on curling acanthus leaves, plants transform into animals and faces appear from vegetation. All of this seems to hang in space in an arrangement showcasing the stylistic expansion of the Renaissance grotesque into a largely unbound, full-field mode, set against a plane of white (fig. 5). Similar bird-human hybrids, paired with decorative sea creatures, emerging from ground lines are seen in both the pages of the French sketchbook (fig. 3) and in the top register of a wall segment of the Loggetta (fig. 5). Additionally, the part-plant, winged beasts from the same sketchbook (fig. 4) bear strong visual resemblance to the forms on the bottom register of the same segment. Furthermore, much of the work here was done in the classical rapid technique of grotesque painting, as recorded by Pliny the Elder, wherein an artist works directly on the wall and produces forms free-hand, thus mirroring the ancient manner of execution in addition to the mode of decoration and architectonics.18

Yet this architectural and decorative transposition from the ruins to the Vatican leaves traces of the heterotopia from whence its imagining came within this space. Due to the fidelity of its imitation, this is a place of collapsed time. Indeed it is much like Foucault’s example of the museum, where the decoration from an “anti-classical” classical past haunts and mingles with the present.19 It is also a place of multiple places, as part of a curial apartment suite and a projection of a ruined, subterranean chamber. But the relationship between these spaces is more complicated; here, an understanding of the Renaissance mindset regarding time and art is crucial.20 This period’s valuation of the past allows for what Thomas Greene terms a “creative anachronism,” which is the conscious and productive use of chronological difference in the making of a synchronous present,21 a mode of thought whereby the calculated imitation of classical art already collapses time.22 Thus, this reimagining of the cryptoporticus and the resurrection of its decorative mode and means of execution in effect suspend the heterotopic, temporal difference at play between the Loggetta and the Domus Aurea. They reintroduce some proximal bundles of relations that tie this space to the larger fabric of the Renaissance. This is what lies in between these spaces: an awareness of the past, the desire for re-completion, and the utility of art in mediating temporalities.

____________________

Tyler Rockey

Tyler Rockey is a PhD student at Temple University specializing in the art of early modern Italy. His research interests include the persistence of the classical tradition, Renaissance-era philosophy and theories of art, antiquities collecting, and the physical, temporal, and semiotic instabilities of ancient sculptures in the early modern context.

____________________

Footnotes

1. For comprehensive discussions of the grotesque style of decoration, see Nicole Dacos, La Découverte de la Domus Aurea et la Formation des Grotesques à la Renaissance (London: Warburg Institute, 1969); Clare Lapraik Guest, The Understanding of Ornament in the Italian Renaissance(Boston, MA: Brill Publishers, 2015); and Alessandra Zamperini, Ornament and the Grotesque: Fantastical Decoration from Antiquity to Art Nouveau (London: Thames and Hudson, 2008).

2. James S. Ackerman, Origins, Imitation, Conventions: Representation in the Visual Arts (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002), 126.

3. Michel Foucault, “Different Spaces,” in Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology, ed. James Faubion (New York: The New Press, 1998), 178.

5. Ibid., 178.

6. Ibid., 181.

7. Michael Squire, “Fantasies so Varied and Bizarre: The Domus Aurea, The Renaissance, and the ‘Grotesque,’” in A Companion to the Neronian Age, ed. Martin T. Dinter and Emma Buckley (Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013), 448.

8. Frances Connelly, “Grotesque,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, ed. Michael Kelly (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), www.oxfordreference.com.libproxy.temple.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199747108.001.0001/acref-9780199747108-e-344.

9. Leonard Barkan, Unearthing the Past: Archaeology and Aesthetics in the Making in Renaissance Culture (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999), 17.

10. Thomas Greene, “Resurrecting Rome: The Double Task of the Humanist Imagination,” in Rome in the Renaissance: The City and the Myth, ed. P. A. Ramsey (Binghamton, NY: Center for Medieval and Early Renaissance Studies, 1982), 42.

11. Roberto Weiss, The Renaissance Discovery of Classical Antiquity, (Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell, 1969), 59.

12. Guest, The Understanding of Ornament in the Italian Renaissance, 369.

13. Greene, “Resurrecting Rome,” 43.

14. Dacos, La Découverte de la Domus Aurea, 105.

15. Zamperini, Ornament and the Grotesque, 124.

16. Nicole Dacos, The Loggia of Raphael (New York: Abbeville Press Publishers, 2008), 29.

17. Nicole Dacos, Per la Storia delle Grottesche: La Riscoperta della Domus Aurea (Rome: Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato, 1966), 48.

18. Dacos, The Loggia of Raphael, 34.

19. Foucault, “Different Spaces,” 182.

20. Aaron J. Gurevich, “Medieval Culture and Mentality According to the New French Historiography,” European Journal of Sociology 24, no.1 (1983): 194.

21. Thomas Greene, The Vulnerable Text: Essays on Renaissance Literature (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986), 221.

22. Alexander Nagel and Christopher S. Wood, Anachronic Renaissance (New York: Zone Books, 2010), 18.

Small Twigs and Withered Plants: Mimesis and Miniaturization in World War I Landscapes

by Tobah Aukland-Peck

A Model of a Devastated Town (1920) (fig. 1) revels in the minutiae of disintegration. The walls of the church in its center are blown out, with its bell tower rising precariously above. Around the church are fallen beams, burned roofs, and dead trees—all meticulously crafted by modelmakers. At London’s Imperial War Museum (IWM), which opened originally at the Crystal Palace in 1920, visitors could lose themselves in the wreckage, searching in vain for survivors, puzzling out the words that remained legible over a shop door, and peering in the gaping windows of the homes still standing.1 Like most miniatures, Devastated Town conjured the enchantment of the real. It sought authenticity by using actual sticks for trees, adding resin to render the river shimmering and reflective, and piling sand and dirt in the road. The tangibility of the materials bolstered a feeling of imminence; a year after the Armistice, British citizens could feel the rage of battle anew.2 This model, which purported to show a French town ruined by enemy bombing during World War I, used its mimetic effect to reconstitute an environment pushed beyond the reach of imagination both by distance and the alienating calamity of mechanical warfare. The haptic proximity of the model was borne, however, from a source closer to home.

The supplies that performed the work of the model’s illusion were sourced from debris of British soil: twigs, plants, sand, and dirt taken from city parks. In this substitution of material experience, the local mimicked the distant violence of war. Twigs picked from British parks metamorphosed into the shell-scarred trees of the French battlefront. The model operated in a physically enclosed world and the objects within had a dual referentiality. They interacted with one another—the twigs that represented the trees in Devastated Town were of like size and depended on collective scale to evoke a realistic space. Yet they also engaged with their counterparts in the real world: the viewer could realize the relationship between the twigs and the trees outside.3 The uncanny nature of the model derived from this simultaneous internal and external signification. By using their imagination to explore the physical world of the model, the viewer treated it like real space—a gesture that bypassed the contradiction of internal realism with external material.

A Model of a Devastated Town was one of approximately fifteen models exhibited at the IWM galleries when they opened to the public in 1920. The newly opened museum evoked the experience of war by combining the actual guns used on the battlefront with paintings, watercolors, and prints by war artists, along with photographs, maps, and models. The miniature scale of the models stood in contrast to the full-size objects—like weapons and regimental banners—that had actually seen combat. Susan Stewart’s work on the ontology of the miniature cites the mediated experience of modernity, in which authentic experience is defined by the “myth of contact,” an imaginary gesture rather than the actual bodily experience of the tangible world. “The memory of the body,” she writes “is replaced by the memory of the object."4 The role of the miniature in the transposition of knowledge from body to mind starts in childhood, when dolls and toys are—like the French village in Devastated Town—animated through the alchemy of material and imagination. This familiarity of the model in early pedagogical exercises for abstract thinking opened up the space of the model as an immersive corollary to these relics of war.

The detail of the models may, at first, link them with the realism of battle paintings in nearby galleries (such as John Singer Sargent’s Gassed [1919]).5 However, the imagination required to animate the models pulled them outside the realm of traditional representation and aligned them, instead, with the most radical experimental image borne of the war: the aerial image. I propose this connection for reasons both practical and theoretical: models in this period were produced based on both aerial photography and topographical maps resulting from aerial reconnaissance. Once the models were installed in the museum, a visitor standing over them would take the place of the aerial eye. The role of scale, an essential aspect of the model’s function as both object and fantasy space, is evidenced in a photograph of visitors at the IWM gathered around the model (fig. 2). The modelmakers ensured that the height of display cases remained consistent and accessible for close contemplation, thereby facilitating a bird’s eye perspective. This was not the view of the soldier but the view of the reconnaissance plane.

The two genres also shared a reliance on imagination as an interpretive and animating force. This way of seeing was particularly relevant to the altered topography of World War I, as subterranean trenches and a reliance on aerial reconnaissance shifted the strategic relationship between space and vision. The view from the ground was limited and unreliable. The view from the air was what mattered.6 If the models provided a familiar entrée to the unfamiliar terrain of war, aerial paintings, as the 1920 IWM catalogue emphasizes, were alienating: “Artists here were guided by no traditions and had to work from eye memory. … They show sights which the imagination must be kindled to realise… It is not to be expected that every groundsman will find air-pictures as lucid as normal landscapes.”7 Notable here is the creative leap. This is a visual strategy that must be learned.

Though battle models have a history that predated the advent of aerial warfare, the physical proximity of A Model of a Devastated Townto aerial paintings and photographs in the IWM galleries recontextualized their format in relation to aerial vision.[8] Images such as Christopher Nevinson’s Over the Lines (1917) (fig. 3)—on display nearby Devastated Town in the Air Force section of the IWM—revealed aerial imagery as schematized rather than representational. Nevinson’s composition has a uniform ground of gray-green and the scant topographical differentiation reiterates the muddy sameness of the front. The staccato lines of white, black, and ochre used to form the town below imply a violent disintegration of the built environment. The horror of war, however, is removed, and the exploding shells in the aerial composition appear as ornamental rather than deadly.

Nevinson’s view incorporated information about roads, trenches, and troops with information indicated by abstract symbols rather than a pictorial match between signifier and signified. The genre of aerial-landscape paintings was facilitated by two mechanical innovations of the early twentieth century that augmented the limits of human vision: reconnaissance flights and aerial photography.9 Its format claimed a scientific lineage which, as the IWM catalogue makes clear, required a trained viewer to make the images lucid.10 Even in the context of an art exhibition, the viewer took on the role of a trained military observer by reading the distant marks of Over the Lines as the details of a ruined town. This is, as the catalogue implies, a drastic departure from the conventions of British landscape painting, where clarity and legibility were highly valued. Landscape imagery, which was vital as an informational tool in past wars, had been rendered obsolete by the symbolic vision of aerial reconnaissance. The explicitness of the miniatures circumvented this troubled relationship between human observation and mechanical vision, presenting a claim for unmediated reality. In the galleries of the IWM, the models translated the remote landscape seen in images such as Over the Lines into a form that reestablished stable topographical vision. Yet their precision and tangibility were an anachronism, and the irony of the models is that they were, unlike aerial paintings and photography, products entirely of the home front.

If authenticity was achieved by some war artists through first-hand experience, the modelmakers, for the most part, had not personally witnessed the episodes or landscapes they were tasked with creating. Instead, for objects such as Devastated Town, the IWM would send the modelmaker maps, aerial photographs, and artist sketches to assist with the production of the scene. Just as the war on the ground became dependent on topographical information gleaned from the air, the maps and photographs used to construct these models in the removed workshops of London were dependent on mechanical vision. The modelmakers had the expertise to translate aerial viewpoints into standard visual conventions. They acted as invisible mediators between the museum visitors and the military, asserting the landscape of war as comprehensible despite the distance from the frontline and the violence of the battle.

The town in Devastated Town was, however, as indistinct as the one in Over the Lines. A later caption notes that the model was intended to represent the war-time condition of a number of French villages and to show the rampant destruction of war to a British populace whose own land, in this period before the Blitz, was relatively untouched.11 Like the nameboard of an obliterated village, the model stood as a record of loss. It showed a landscape that was particular to the war as a whole—as troops and shelling moved through civilian towns in northern France—rather than a specific time or location. The implied reality of the miniature, in its intense detail and promise of a completely enclosed world, seemed to deny its composite nature. Like the literary referents of Barthes’s reality effect, the models marshal excessive detail to conjure a convincing simulacrum of place.12

While the IWM intended to display the efforts of the entire military and civilian population in the war and had sections devoted to domestic efforts, none of the models shown at the Crystal Palace were of British sites. When a modelmaker wrote to the museum to suggest a model of the damage done by the first zeppelin bomb dropped on London, the institution declined, citing space restraints.13 The inclusion of this scene would have disrupted the contrived certainty of models of the war’s terrain. A violent spectacle that had torn through buildings and streets mere miles away from the museum would have broken the enclosure of the models. The safe distance—borne of the models’ aerial viewpoint, miniaturization, and representation of a general type rather than a specific place—would be negated by the immediacy of the local zeppelin damage. The threat of the lived experience would be brought dangerously close to home; imagination would not be necessary to bridge the gap between knowledge and experience.

The simulacra of foreign battlefields were ultimately marshalled as psychological barriers between the field of war and the home front. The clarity of their construction circumvented the necessity of experienced vision required by other documentation of the twentieth century’s first mechanized conflict. They allowed “groundsmen,” as the IWM catalogue notes, to attain lucidity. The models were consistently and repeatedly focused on distant locations and did not threaten the integrity of the British landscape in the face of world war. The supplies that performed this work, however, were physical remnants of the British soil, marking the scene as a foil to the unscathed landscape of Britain. The museum’s lead curator wrote to the superintendent of Hyde Park in 1919:

I beg to inform you that a number of Relief Models showing various portions of the Western Front and War Areas are being prepared by this Department […] To complete these models, it is necessary to insert small twigs and withered plants on a scale suitable to the model. I shall be obliged therefore if you will allow Mr. Ogilvie, the bearer of this letter, to select such small specimens as occasion may demand, it being of course understood that none of these specimens would be taken from flower beds, only from the wilder parts of the park.[14]

Though the miniature world transformed twigs and plants into approximations of foreign terrain, their attachment to British parkland threatened to undo the model’s claim of authenticity. To maintain the illusion of British control over the distant battlefield, it was integral that both the modelmakers, and the war itself, would not disturb the flower beds.

____________________

Footnotes

1. Since 1936, the IWM has been located in Lambeth. The museum vacated the Crystal Palace and moved to South Kensington in 1924. The Crystal Palace at Sydenham was the glass structure designed by Joseph Paxton to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. It was moved from Kensington to Sydenham in 1852.

2. In this way, these models share a history with earlier battle panoramas, such as those exhibited in France and England during the Napoleonic wars. It is important to note that this tradition was modernized during WWI through large-scale photographic panoramas that were similarly intended as mimetic performances; see Martyn Jolly, “Composite Propaganda Photographs during the First World War,” History of Photography 27, no. 2 (2003): 154–65. These experiences, however, were often staged as separate performances, and the models are distinct in their use as part of the newly conceived military museum.

3. Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993), 45.

4. Stewart, On Longing, 134.

5. Gassed (1919) was one of the largest paintings included in the art section of the IWM galleries. Sargent, an American, was commissioned by the British Ministry of Information in 1918 to travel to the front, where he completed research for this work. The painting remains in the collection of the museum.

6. This representational shift is documented by scholars including Bernd Huppauf and Hanna Rose Shell; see Bernd Hüppauf,“Representing Space — Panoramas of World War I Battlefields,” History of Photography 31, no. 1 (2007): 83–84; Hanna Rose Shell, Hide and Seek: Camouflage, Photography, and the Media of Reconnaissance (New York: Zone Books, 2012).

7. Imperial War Museum, Catalogue of Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1920), 4

8. Military wargames, which used tabletop surfaces augmented with topographical details to plan troop movements, were invented in Prussia at the turn of the nineteenth century. They were popularized in England by author HG Wells, who published Little Wars, a guide to tabletop war games, in 1913.

9. Caren Kaplan summarizes the scientific and militaristic implications of aerial vision in her chapter about aerial mapping projects in early twentieth-century Iraq; ee Caren Kaplan, Aerial Aftermaths: Wartime from Above (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018), 138.

10. Allan Sekula’s article on Edward Steichen’s role as commander of the aerial-photography branch of the American Expeditionary Force during the First World War is an early contribution to the field of aerial photography. His analysis echoes many of the points that I pull from the IWM catalogue caption, including the “rationalized act of ‘interpretation’” that constitutes any visual interaction with the aerial image;see Allan Sekula, “The Instrumental Image: Steichen at War,” Artforum 14, no. 4 (December 1975): 26–35.

11. While the IWM identifies some images of this model as “A Model of Peronne” I believe that this caption, included with the catalogue entry for the model itself, supersedes this later identification.

12. Barthes proposed the reality effect in a 1968 essay. He originally applied it to literary models. He distinguished between textual details that relate specifically to the main plot—called predictive—and details that are descriptive but superfluous to the story, notations. The extraneous details play upon the reader, building an experience that heightens the sense of the text’s reality, see Roland Barthes,The Rustle of Language (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1989), 141–48.

13. Correspondence from Major C. Foulkes to Charles Ledwidge, January 24, 1922, EN1/1/MOD/001, The Imperial War Museum Archive, London.

14. Correspondence from Major C. Foulkes to Hyde Park Superintendent, February 21, 1919, EN1/1/CPL/020. The Imperial War Museum Archive, London.

Phillippa Pitts interviews Mingqian Liu and Amanda Thompson

Editors’ Introduction

by Rebecca Arnheim and Bailey Benson

When the theme of “Environment” was selected for the 36th Annual Boston University Graduate Symposium in the History of Art & Architecture, we could not imagine how profoundly relevant it would be for the year 2020. The year began with bushfires in Australia that burned more than 46 million acres of land. Intense monsoons severely impacted several countries in Asia and abnormally heavy rainfall in Sudan and Ethiopia resulted in devastating flooding. In the United States, wildfires rage more frequently and with greater intensity in the West of the country, tornado season in the Midwest is getting progressively longer, and tropical storms and hurricanes regularly ravage the southern and eastern coastlines. These are only a few examples of the increasingly common natural disasters that have occurred this year. Then, a novel coronavirus hit the world stage.

Global concerns surrounding COVID-19 reached a fever pitch in early March, just weeks before the symposium was scheduled to take place. The venue was set, speakers had booked their travel, and all things appeared to be proceeding as planned. Almost overnight the whole situation changed. It became increasingly apparent that this event, as with so many others, would not be able to take place as scheduled. After serious deliberation with both the faculty members of the History of Art & Architecture Department at Boston University and representatives from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the difficult decision was made to cancel the symposium. This special edition of SEQUITUR features papers from that canceled symposium.

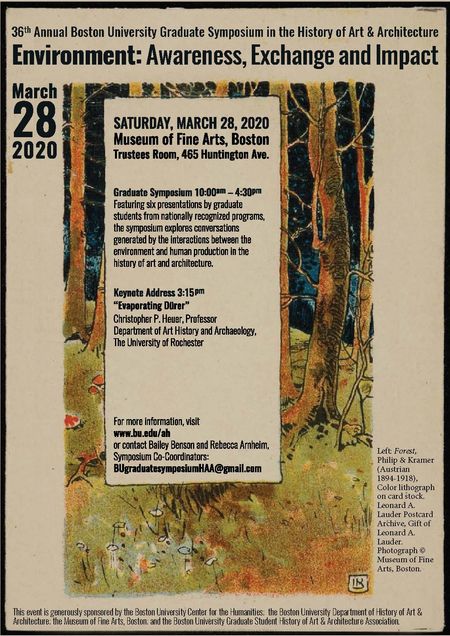

This year’s graduate symposium was planned for March 28, 2020, at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. This event was intended to explore the relationship between the environment and artistic and architectural production (fig. 1). Six graduate students from across the country were invited to share their research, and a keynote address was to be presented by Professor Christopher P. Heuer (University of Rochester). The graduate student presenters were: Tobah Aukland-Peck (The Graduate Center, CUNY), Rachel Kase (Boston University), Mingqian Liu (Texas A&M University), Carolyn Russo (American University), Amanda Thompson (Bard Graduate Center), and John White (University of Massachusetts Amherst). The speakers were to be divided into two panels of three presentations each. The morning session, “Reclaimed by Nature,” was to feature papers focused on nature overcoming human creation and artists’ corresponding reactions. While the morning session focused on nature’s triumph, the afternoon was expected to explore human accomplishments against nature’s forces in a session entitled “Claiming Spaces.”

The present issue of SEQUITUR features papers from four of the presenters. The organization of this issue is intended to reflect that of the event itself (fig. 2). The two parts mirror the two panels, and the papers are presented in the order they would have been delivered at the symposium. Two video Q&A sessions were also recorded in which the authors and the original session moderators, Willie Granston and Phillippa Pitts respectively, further discuss the papers.

The issue begins with Rachel Kase’s paper, which investigates the Little Ice Age’s artistic representations in Dutch art. Kase demonstrates how the monochromatic representations of winter-obscured landscapes disoriented viewers and created instances of “non-sites” in Netherlandish artistic productions. Tobah Aukland-Peck uses miniature displays of World War I battles on display in the Imperial War Museum in order to explore how British citizens dealt with and understood war events that occurred on foreign soil. The choice of materials used to create these models ultimately came to play a central part in how the war was presented to the British citizenry.

Mingqian Liu looks at the built environment, discussing the impacts of preservation efforts on the residents of an 800-year-old historic neighborhood in Beijing, China. Her paper uses interviews with those residents to argue for a bottom-up approach to preservation practices, one that considers the residents and their daily interactions with their built urban environment. The concluding paper of the issue is by Amanda Thompson and deals with the relationships between objects, their makers, and the collections they become a part of—in this case, the British Museum. Thompson uses the example of an eighteenth-century Cherokee basket to demonstrate Native relationships to the environment through the act of weaving and how baskets come to function as objects of land claims as they move into settler spaces.

We hope that this special issue of SEQUITUR invites readers to rethink their own relationships with their environments, both natural and human-made. How does our environment shape us, and how do we shape our environment? The papers featured in this issue serve as good starting points for conversations that can continue outside of the print medium, generating new dialogues and avenues of investigation.

A Sustaining Cherokee Basket: Colonial Inscription and Indigenous Resistance

by Amanda Thompson

One of my Cherokee elder aunts tells me baskets are living things. She believes the materials she uses in her weaving give the baskets everlasting life. “When we weave a basket, it is held close to our body so as to impart our spirit into the basket. When you give a basket, you give a part of your spirit,” she says.[1]

—Author and poet MariJo Moore (Eastern Cherokee, Dutch, and Irish ancestry) in “The Spirit of a Cherokee Basket”

A large Carolina basket made by the Indians of splitt canes some parts of them being dyed red by the fruit of the Solanum magnum Virginianum racemosum rubrum & black. They will keep any thing in this from being wetted by rain. From Coll. Nicholson Governor of South Carolina whence he brought them.[2]

—Earliest catalogue description of a Cherokee basket acquired by the British Museum in 1753

The two texts which begin this essay communicate disparate understandings of a Cherokee basket.[3] Although written centuries apart, cultural rather than temporal differences separate them. The first presents the conceptions of generations of the author’s Eastern Cherokee ancestors that a basket is a living thing, with a continuous, intimate, and inextricable connection to the sources of its natural materials and to its maker. The second, written to identify an object in the British Museum’s collection, represents the basket, its materials, and its maker as colonized subjects. Considering the object life of that eighteenth-century doubleweave Cherokee basket in the collection of the British Museum (fig. 1–2), I will draw on the tension between these two ways of understanding a basket to weave an essay which unsettles the authority of a colonial institution’s collecting and cataloguing of a Native-made basket and exposes that authority as an agent of settler colonial violence.

Guided by the counsel of Tuscarora art historian Jolene Rickard that “even the most ‘traditional’ form, like basket weaving, is actually a demonstration of Indigenous renewal, survival, and political and environmental awareness,” I aim to access Cherokee basket makers’ “strategic cultural resistance,” and to illustrate how colonial agents acted to neutralize and erase this resistance, conforming to the “elimination of the Native” required by the settler colonial structure.[4] I conclude by considering the maker and, responding to an archival lack, imagine her agency in entering the basket into the colonial networks of exchange and demonstrate how the maker’s act of “strategic cultural resistance” has lived on to renew Cherokee political and cultural agency. As a non-Native scholar, this imagining is in the form of queries, shaped—like all my scholarship—--by what I have learned from many Native thinkers. This mode of narration is influenced by African-American scholar Saidiya Hartman who “exploit[s] the capacities of the subjunctive… both to tell an impossible story and to amplify the impossibility of its telling.[5] My queries aim to illuminate other ways of considering the unknown maker’s agency, without speaking for her.

“The Spirit of a Cherokee Basket”

Basketry is woven into Cherokee cosmological, ecological, ancestral, and community relationships. Historically, women made baskets to be used for trapping, harvesting and processing food, storage, transporting goods, and bartering, among other subsistence activities.Baskets also had ceremonial purposes, such as to protect and contain the power of ritual tools and garments. They feature prominently in Cherokee stories, such as that of Selu, the Corn Mother, who used baskets to catch the corn and beans which she shook from her body to nourish her children, and of Kanane-ski Amai-yehi, or Spider-Dwelling-in-the-Water, who wove a basket to bring fire to the earth.[6] In these stories and practical uses, baskets are sustaining vessels central to Cherokee ways of being.[7]

Basketry has also supported Cherokee continuance. For instance, following the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and subsequent forced migration of thousands of Cherokees, Cherokee Nation scholar Karen Cooper Coody describes:

Upon arrival in Indian Territory, bereft of adequate household items, the vast majority of Cherokee women would have immediately set to work producing a needed array of workbaskets. … Most women were faced with endless tasks of tending sick and weakened families, feeding them, sewing and mending worn-out clothing, weaving new cloth and making quilts, planting household gardens, cooking and foraging in unfamiliar Ozark woodlands or grasslands for plants suitable for food, medicine and craft materials [such as basketry].[8]

After devastating loss, Cherokee women managed their survival by adapting their ancestral art to the materials available in unknown territory.[9] Returning to their tradition of weaving allowed for the renewal and resurgence of peoples—not just through a basket’s utility, but also through ensuring that cultural knowledge could live on, changed but resilient.

Basketry also provides rhetorical means for renewal and decolonization. Cherokee/Appalachian author Marilou Awiakta identifies a doubleweave basket as the “natural form” of her book Selu: Seeking the Corn-Mother’s Wisdom:

As I worked with the poems, essays, and stories, I saw they shared a common base—the sacred law of taking and giving back with respect, of maintaining balance. From there they wove around four themes, gradually assuming a double-sided pattern—one outer, one inner—distinct, yet interconnected in a whole. … Reading will be easy if you keep the weaving mode in mind: over… under… over… under. A round basket never runs “straight-on.”[10]

The complicated process and ultimate strength of doubleweave enables Awiakta to reckon with modern environmental destruction and reweave a restorative vision of futurity for her readers. Similarly, Qwo-Li Driskill uses doubleweave as a structure in their 2016 book Asegi Stories: Cherokee Queer and Two-Spirit Memory, which weaves together personal and theoretical writings to create a third space (“between the basket walls”) in which to decolonize Cherokee-specific traditions of gender and sexuality.[11] Thusly, basketry has sustained Cherokee life and culture through baskets’ practical uses, in the perpetuation of traditions of knowledge, and by providing a framework for resurgence and decolonization—all despite colonial efforts to decontextualize baskets and disenfranchise their Native makers through collecting and cataloguing.

“A large Carolina basket”: Collecting and cataloguing as settler colonial inscription

The catalogue cited at the start of this essay is the earliest known record of the British Museum’s doubleweave basket.[12] Although the writer is unidentified, the language they use to describe the basket illuminates a colonial framework for their knowledge, with idioms encoded to naturalize colonial power. The basket is first identified as a product of a place inscribed with a colonial name: Carolina. The colony of Carolina was granted its charter and named by King Charles II of England in honor of his father, erasing the historic and ongoing identifications of lands by the peoples native to them and instead providing an Anglo-monarchical ancestry.[13] The basket is secondly identified by the generic “Indians” who made it, eliding the diverse Native polities of North America into one undistinguished other.[14] The plant whose dyes provide the basket’s contrasting design is called after Britain’s supposed virgin queen, Elizabeth I, literally overlaying British power onto plants indigenous to the colony, in an act of “linguistic imperialism” which classified and so claimed the plant life of the world.[15]

This cataloguing enacts epistemic violence we now identify with settler colonialism. Citizen Potawatomi Nation scholar Kyle Powys Whyte writes that settler colonialism necessitates “homeland inscription,” as “settlers can only make a homeland by creating social institutions that physically carve their origin, religious and cultural narratives, social ways of life and political and economic systems (e.g. property) into the waters, soils, air and other environmental dimensions of the territory or landscape. That is, settler ecologies have to be inscribed into indigenous ecologies.”[16] Settler colonialism has been inscribed into the archive of this basket by renaming its homelands and the natural materials from which it was woven and by flattening the diverse peoples of Native North America into a single, othered, Indian. This inscription supports the “structural genocide” of settler colonialism through appropriation of lands and assimilation of peoples.[17]

As its maker and community has been excised from its archival record, the written provenance of this basket begins with its ownership by a colonial agent. South Carolina governor Francis Nicholson possibly collected it as a gift from Native delegations, such as when he negotiated the first colonial treaty with Cherokees in 1721. In meetings with the multiple Native communities of South Carolina, Nicholson sought to gain information and establish boundaries and trade relations, while Native delegations took the opportunity to affirm their sovereignty. Gifts like maps and baskets asserted rights by demonstrating Native territories, resources, geographical and ecological knowledge, and existing trade and political relationships. While Native people strategically gifted maps and baskets to make political, economic, and territorial claims in their meetings with colonial authorities in the eighteenth century, other Southeastern Native nations—such as the Chitimacha and the Coushatta—have used baskets to strategically advance land claims into the twentieth century.[18]

Rather than acknowledging the rights asserted with these maps and baskets, Nicholson entered them into a collection supportive of Britain's empire-building project by transferring them to Sir Hans Sloane. A leading London intellectual, Sloane used his position and wealth to comprehensively collect flora and human-made objects from throughout the empire, supported by British agents acquiring local specimens.[19] Sloane collected in order to build knowledge, which in turn supported Britain’s expanding empire and commercial interests.[20] Botanical knowledge enabled the classification, cultivation, and capitalization of the natural products of colonized lands.[21] Objects made by peoples throughout the empire educated British people about colonized subjects and supported an imagined hierarchy of civilization with British culture at the pinnacle and other cultures below.[22]

Upon Sloane’s death, British Parliament complied with his testamentary wishes that the collection be kept together and made publicly accessible by establishing the British Museum in 1753. This progressive move towards public education enabled all those able to visit to observe and learn about world cultures. But the London museum also facilitated the expansion of the logic of colonialism, as visitors could imagine their place at the center of empire and internalize hierarchies of a civilized center superior to uncivilized others which Sloane created in his collection. By spreading the logic of colonialism amongst the public, subjugation, resource extraction, and dispossession were normalized as an inevitable—and benevolent—right of Britain. The transformation of a Native diplomatic gift into an object in a national collection at the center of empire enacted settler colonialism by providing proof of ownership of Native land and of the incorporation of Native peoples at the seat of colonial power.[23]

Conclusion

In resistance to the epistemic violence of settler colonialism which severed this basket from its cultural context, I believe it is powerful to acknowledge the part of the unidentified maker’s spirit given with the basket, recalling the opening words of MariJo Moore. What if she intended this basket to demonstrate Cherokee rootedness in their homelands? What if she staked a claim by mobilizing the knowledge of generations of ancestors who learned to cultivate the land and transform its plant life into a watertight basket? What if she meant to build a relationship through the gifting of this basket, with the expectation of reciprocity and respect, in line with Cherokee relationship-based governance? What if this basket was woven as a material manifestation of Cherokee sovereignty? The intentions and expectations of the maker’s spirit have been excised in the basket’s collection and cataloguing in order to inscribe settler colonialism onto the peoples, land, and ecology from which it came, in another deliberate act of dispossession.

In 1940, Eastern Cherokee basket maker Lottie Stamper used images of this basket to further her knowledge of the doubleweave technique and then teach it to others (fig. 3).[24] In this way, Stamper refused the co-option of the basket by the colonial state, and instead accessed the ancestral knowledge embodied in the basket to enable the technique’s renewal in the community. Eastern Cherokee artist Shan Goshorn, who passed away in 2018, drew from the knowledge revitalized by Stamper and used strips of treaty texts, historical photographs, and other documents to weave paper baskets which spoke powerfully to the injustices of the United States against Native peoples (fig. 4). Goshorn’s basketry demonstrates how an eighteenth-century basket continues to sustain Indigenous renewal and strategic cultural resistance.[25]

____________________

Footnotes

[1] MariJo Moore, “The Spirit of a Cherokee Basket,” Fiberarts 28, no. 4 (February 2002): 25.

[2] “Basket,” British Museum, accessed March 9, 2020, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/E_Am-SLMisc-1218-a-b.

[3] Cherokee peoples are indigenous to homelands throughout the Southeast of the territory now known as the United States. In the nineteenth century, the United States government forcibly moved thousands of Cherokees to Oklahoma to open up land to settlers. Today, there are three recognized tribes of Cherokees: the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians and the Cherokee Nation, both in Oklahoma, and the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in North Carolina—all of whom maintain basketry traditions. In this paper, I refer to the culture both generally and pre-removal as Cherokee.

[4] The basketry quotation comes from Jolene Rickard, “Uncovering/Recovering: Indigenous Artists in California” in Art, Women, California 1950-2000: Parallels and Intersections, ed. Diana Burgess Fuller and Daniela Salvioni, (Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2002), 145. The term “strategic cultural resistance” is drawn from Jolene Rickard, “Visualizing Sovereignty in the Time of Biometric Sensors,” South Atlantic Quarterly 110 (Spring 2011): 474. While in the latter essay, Rickard engaged with contemporary “Haudenosaunee artists [who] visualize sovereignty through key episodic ‘traditional’ or historical moments” (474-75), I find the idea broadly useful in thinking politically and critically about historic and contemporary Indigenous arts. The term “elimination of the Native” comes from a foundational text of settler colonial theory by Patrick Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (December 2006): 387-409. Wolfe asserts a “structural genocide” (403) as concomitant with settler colonialism, enacted not just by mass killings but also removal from lands, removal from tribes, enforcement of a grammar of race, and assimilation.

[5]Abridged for length in the body of my essay, I think it necessary to include this quotation in its powerful entirety: “By advancing a series of speculative arguments and exploiting the capacities of the subjunctive (a grammatical mood that expresses doubts, wishes, and possibilities), in fashioning a narrative, which is based upon archival research, and by that I mean a critical reading of the archive that mimes the figurative dimensions of history, I intended both to tell an impossible story and to amplify the impossibility of its telling”;Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 12, no. 2 (June 1, 2008): 11.

[6] James Mooney, Myths of the Cherokee (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1902), 242, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/45634/45634-h/45634-h.htm#s2. Still today “these stories and the teaching that come from them create and maintain the everyday reality for the Eastern Cherokees”; Sandra Muse Isaacs, Eastern Cherokee Stories: A Living Oral Tradition and Its Cultural Continuance (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2019), 100.

[7] For information on Cherokee basketry, see M. Anna Fariello, Cherokee Basketry: From the Hands of Our Elders (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2009) and Sarah H. Hill, Weaving New Worlds: Southeastern Cherokee Women and Their Basketry (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1997). It is likely the British Museum basket is actually two separate pieces—a basket and a tray—miscatalogued as one piece due to the similarity of sizes and technique. Anthropologist Betty Duggan believes they might represent the work of two different makers, and resists an absolute attribution to a Cherokee maker, rather than to other peoples indigenous to the region; Betty J. Duggan, “Baskets of the Southeast” in By Native Hands: Woven Treasures from the Lauren Rogers Museum of Art, ed. Stephen W. Cook and Jill R. Chancey (Laurel, MS, Seattle, WA: Lauren Rogers Museum of Art, University of Washington Press, 2005), 36.

[8] Karen Coody Cooper, Oklahoma Cherokee Baskets (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2016), 27.

[9] Cherokee makers experimented with the different plants found in Oklahoma and adjusted to their qualities and gathering seasons. Eventually, buckbrush root became the primary basketry material of Oklahoma Cherokees, combined with oak stays. Similarly, Eastern Cherokee basket makers had to adapt to environmental changes wrought by settlers. As cane became less prevalent Cherokee women innovated basketry techniques and designs in oak and root runners in the early nineteenth century, the introduced or invasive Japanese honeysuckle root runner in the later nineteenth century, and fast-growing maple in the early twentieth century. Contemporary makers use all these materials to continue to innovate new forms and designs.

[10] Marilou Awiakta, Selu: Seeking the Corn-Mother’s Wisdom (Golden, CO: Fulcrum Pub, 1993), 34.

[11] Qwo-Li Driskill, Asegi Stories: Cherokee Queer and Two-Spirit Memory (Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona Press, 2016), 5.

[12] Cataloguing is a practice that museums use to describe objects. It is a step in the acquisition process, as knowing creates ownership. Its classifications impose culturally contingent knowledge upon objects, which continue to determine understandings and access to objects to the present; see Ramesh Srinivasan, Robin Boast, Jonathan Furner, and Katherine M. Becvar, “Digital Museums and Diverse Cultural Knowledges: Moving Past the Traditional Catalog,” Information Society 25 (2009): 265-78 and Hannah Turner, “Decolonizing Ethnographic Documentation: A Critical History of the Early Museum Catalogs at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History,” Cataloguing & Classification Quarterly 53 (August 2012): 658-76.

[13] The colony of Carolina was chartered in 1663 and split into two colonies—North and South Carolina—in 1712. As the singular “Carolina” is used in the catalogue description, it is likely that in England the two colonies were still referred to as one despite their administrative division.

[14] See Jodi A. Byrd, The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism, First Peoples: New Directions in Indigenous Studies (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2011) on the collapsing of diverse Indigenous polities into a racial Indianness as a tool of settler colonialism in the United States.

[15] Londa L. Schiebinger, Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004), 195. The acts of classifying plants and cataloguing objects similarly subordinate local knowledge to that of the empire.

[16] Kyle Powys Whyte, “Indigenous Experience, Environmental Justice and Settler Colonialism” in Nature and Experience: Phenomenology and the Environment, ed. Bryan E. Bannon (London, New York: Rowman & Littlefield International, 2016), 171-72.

[17] Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native”: 403.