news

Fabricated Faces: Obscured Self-Portraiture in the Works of Jo Spence and Mary Sibande

by Michaela Peine

Jo Spence (1934–1992) explored the potential for activating this liminal space between self and “other” through her self-reflective photographic work. Collaborating with Rosy Martin, Spence explored “phototherapy,” a therapeutic project in which Spence used photography sessions to emotionally embody different figures from her history, transforming into family members, younger versions of herself, or even repressed aspects of her personality.2 Although they are overt representations of herself—literal self-portraits—these photographs highlight Spence’s understanding of the mutability of this medium. She creates obscured self-portraits, images that hide or replace the artist, which seem to subvert the purpose and expectation of directly representational self-portraits. Spence’s obscured self-portraits reveal the deeper complexity of her inner life; she assumes a multitude of identities even as she offers her external image to the viewer.

Over the course of her work, Jo Spence studied what it means to capture a self-portrait that is not only an image of oneself, but also reveals insight into the multiplicity of one’s identity. Spence pushes even further in The Final Project (1991–1992), a final series of photographs spanning the last two years of her life following a decade-long battle with breast cancer and subsequent diagnosis of leukemia. Spence’s work in this period focuses on forcing the viewer away from the objectification of her—as a woman, as a one-dimensional human, or as a passive patient suffering from illness—towards subjectification, wherein the viewer accepts the diversity of her complex individuality. Through the photographs of The Final Project Spence creates “hidden” self-portraits where she intentionally objectifies and conceals herself, replacing her own body or face with symbolic objects and images. As the viewer searches for Spence in the photographs, they are forced into a more profound space where they must also confront her intellectual multiplicity and transcendental existence.

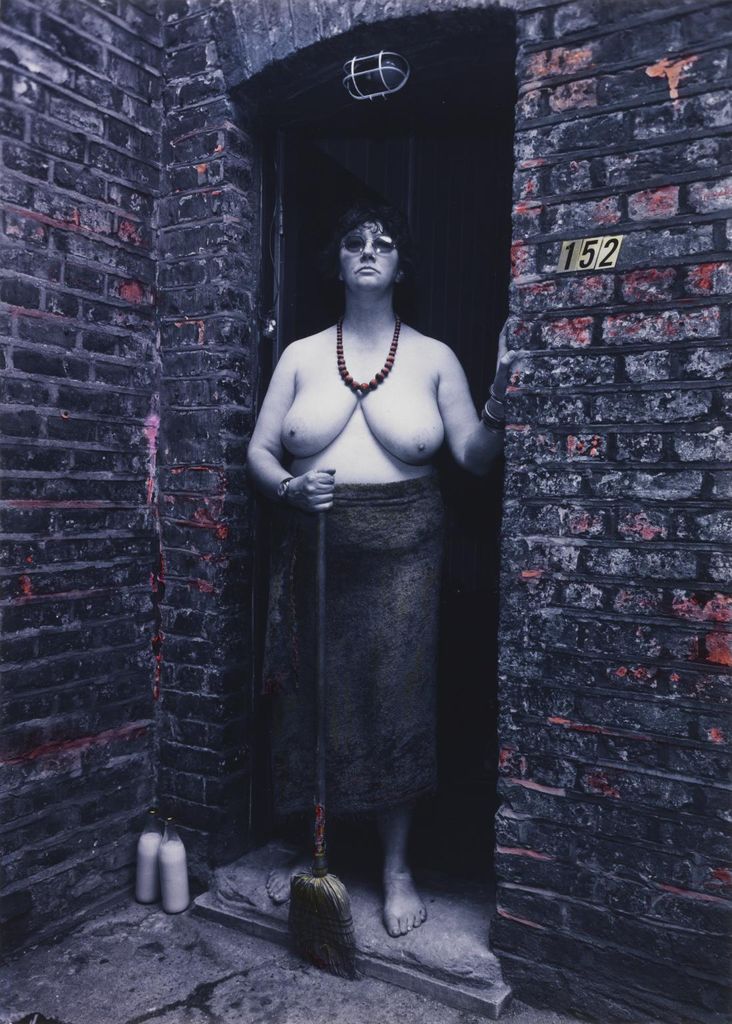

In The Final Project [Various 7] (1991), a single photograph from her project, Spence once again models her own body, turning the camera on her personal experience (fig. 1). Aware of her terminal diagnosis and quickly approaching the end of her physical self, Spence forces her viewer to face this difficult reality. Spence’s self-portrait in [Various 7] is fully obscured; she has replaced her literal face and body with a plastic skeleton.3 In case the skeleton is not immediately obvious as a self-portrait, Spence reinforces this connection by mimicking the composition, location, and coloring of an earlier self-portrait, Remodeling Photo History: Colonization (1981–82) (fig. 2). Both photographs highlight the central figure through shocking white (either the white of Spence’s bare skin or the bones of the stripped skeleton) and surround it with decontextualized material trappings (i.e., the shadowy goods of a store interior, or the domestic broom, beads, and milk jars surrounding Spence). However, it is the stance of the two figures that links them most strongly as self-portraits. In [Various 7], Spence confronts the transformation of herself into a portrait, as evidenced by the skeleton dominating the frame of the image, staring directly at the viewer with the same inscrutable gaze. Meanwhile, in Colonization, Spence hides her gaze behind round dark glasses; she stares directly at us through the black sockets of her skeleton. In both images, Spence occupies a door frame, a liminal space. But while the door of Colonization offers her a portal to step closer to the viewer, the door in [Various 7] has undergone the same transcendental transformation Spence will transverse through death. Essayist Anne Boyer writes that “to look at a skeleton—a human-like form that has shed the imposed visual markers of race, gender, and class—is to see the erasure of social inscription, to look on a post-identity democracy of the dead.”4 We see Spence’s skeleton in the door, but we are separated from it by a pane of glass and a “closed” sign. We may look upon her, but she is no longer accessible to us. Instead, we are left to contend with her spiritual identity; viewing her photographs after her death, we must confront the ways she does or does not live on.

Also challenging our perceptions of her identity, Mary Sibande (1982–present) performs a parallel sleight-of-hand with her self-portrait. Born in apartheid-era South Africa, Sibande combines fashion design, sculpture, and photography to similarly confront the questions of created and modified identity. Stepping into the question of the hidden self-portrait, Sibande created “Sophie,” an alter ego sculpture based on a cast of her own body and adorned with flowing, elaborate gowns. While Sophie is a literal copy of herself, Sibande conceals the self-portrait; she assigns it a brand-new identity, “Sophie,” requiring her viewer to grapple with this externalized and disguised selfhood. Although Sibande creates this distance between herself and her self-portrait, she uses the objectification of herself in Sophie to explore her own complex relationship to her history. Scholar Tracey L. Walters describes this approach to self-portraiture, writing, “as both artist and subject, Sibande uses her body to reincarnate her relatives and give them license to claim their own identities.”5 Sibande utilizes her self-portrait not only to resurrect, but also to explore her own identity within the context of her family history.

The daughter of three generations of domestic workers, Sibande first dressed Sophie in blue-and-white, colors synonymous with the profession; however, Sophie encapsulates many seemingly contradictory identities (fig. 3). While she wears the colors of a domestic worker, the designs of the gowns are elaborately lavish, mimicking the clothing of the rich women who would hire domestic workers. At times both uniforms and custom high-fashion gowns, the changing array of Sophie’s costumes requires viewers to be constantly assessing and reassessing Sophie’s place in society.6 Looking back to the racism and oppression of apartheid as well as the strength and resilience of her foremothers, Sibande uses her self-portrait—obscured through the interface of Sophie—to encapsulate the contradictory identities of her history. Sophie is a self-portrait and an “other,” the image of a victim and an aggressor, an individual and a nation.

In The Admiration of the Purple Figure (2013), Sibande expands the scope of her mediated self-portraits (fig. 4). Sophie emerges in the photograph wearing bright purple, rather than the Dutch-favored blue of domestic workers. This color bears deep personal, social, and political significance; in the South African Purple Rain protest of 1989, anti-apartheid protesters were sprayed by authorities with purple dye to mark the revolutionaries for arrest. In Admiration of the Purple Figure, Sibande draws sharp attention to this change of color, specifically baptizing Sophie in purple, a personal and political transformation. Although Sophie’s eyes remain closed—gone are the demure poses of her blue iteration—Sophie rises powerfully above a twisting sea of purple forms that seem to worship her yet also be a part of her, connected as if by umbilical cords. No longer does Sophie wear the hoop skirts and puffed sleeves of the apartheid elite, but instead dons a kind of battle-armor and helmet, and the fabrics of her skirt have themselves taken life, becoming the aggressive purple structures blanketing the ground. These same structures stretch to place a circlet on her head, crowning her. Through Admiration we see many forms of rebirth taking place through the specificity of Mary Sibande’s selfhood. Sibande objectifies herself, transforming her body into the character of Sophie; however, this disguised self-portrait provides a liminal space where Sibande forces the viewer to confront the complex identities of her own history.

Through their obscured self-portraits, Jo Spence and Mary Sibande interrogate perceptions of themselves. Spence fully replaces her body, forcing the viewer beyond the physicality of her image to confront her individual spirit that lives past her death. In many ways, Sibande’s self-portraits perform the opposite maneuver; through the objectification of her body, Sibande resurrects the multifaceted histories of those who have gone before her and shaped her. Spence and Sibande challenge our understanding of the self-portrait, pushing the limits of its definition and function. Viewing Spence and Sibande’s self-portraits requires the viewer to meet them in a place of mutual vulnerability, forcing the acknowledgment of their complex identities.

____________________

Michaela Peine received her BA in English and Studio Art from Hillsdale College, specializing in oil painting and portraiture. She is pursuing an MA at the University of St. Thomas studying Art History with a certificate in Museum Studies. She is currently researching contemporary artistic responses to Northern Renaissance and Baroque art, as well as decolonial educational practices in museums.

____________________

Footnotes

1. Amelia Jones provides the baseline for my theories of portraiture and self-staging. Most especially in her discussion on the exaggerated performative qualities of self-portrait photography, Jones lays a groundwork highlighting the self as a tool to be manipulated or transformed. Amelia Jones, “The ‘Eternal Return’: Self-Portrait Photography as a Technology of Embodiment,” Signs 27, no. 4 (Summer 2002): 947–978.

2. Rosy Martin and Jo Spence, “New Portraits for the Old: The Use of Cameras in Therapy,” Feminist Review 19 (Spring 1985): 66–92.

3. Anne Boyer identifies the skeleton motif throughout all of The Final Project as a mutable self-portrait, a commentary on Spence’s imminent death as well as a form of self-immortalization. Anne Boyer, “The Kind of Pictures She Would Have Taken,” Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context, and Enquiry 42 (Autumn/Winter 2016): 4–11.

4. Boyer, “The Kind of Pictures She Would Have Taken,” 6.

5. Tracey L. Walters, “The Art of Dressing Up in Mary Sibande’s Long Live the Dead Queen,” in Not Your Mother’s Mammy (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2021), 127.

6. For a more detailed breakdown of Sibande’s designs for Sophie, read Tracey L. Walters’ chapter.

A Fledgling Baroque: Featherworks from New Spain in Counter-Reformation Europe

by Rachel Kline

Throughout the sixteenth century, Spanish clergy and nobility acquired hundreds of featherworks crafted by the Indigenous artists of New Spain, which arrived on merchant ships in major European port cities from Antwerp to Seville. The artistic tradition of featherwork, or amantecayotl, among the Mexica people of New Spain predated the conquest of Tenochtitlán but was preserved by the Spanish colonists who commissioned Indigenous artists to create Catholic images in the art form. At once objects of Mexica cultural affirmation and evidence of conquest and conversion, sixteenth-century featherworks represented the Spanish possession of the Americas and bridged the impossible distance of empire for collectors who sought to construct a cosmopolitan self-image. European viewers were enthralled by their inexplicability as objects of both human artifice and natural creation so distinct from the mimetic painting of the late Renaissance. Within the context of the Counter-Reformation and the Council of Trent’s (1545–1563) reaffirmation of the role of images in religious practice, featherworks emerge as a non-western influence on the European Baroque, which harnessed the political valence of affect in service of the Catholic Church. By examining Mexican featherworks through a decolonial lens, this paper proposes a thread linking the affective splendor of arts indigenous to the Central Mexican Valley to the emergent Baroque style of Counter-Reformation Europe.

One of the earliest featherworks to arrive in Europe was the pre-Hispanic Ahuitzotl Shield, now in the imperial collections in Vienna (fig. 1).1 Dating to the early sixteenth century, the featherwork shield was crafted by skilled artists known as amantecas, who were trained in the art of amantecayotl. Called chimalli by the Mexica, these featherwork shields were often used in ritual performances and were particularly valued for the ways in which the image crafted from feathers responded to the vibrant effects of ambient light, granting them an affective power.2 Often received as tribute to the Aztec Emperor, or tlatoani, extravagantly decorated featherwork shields can also be read as material manifestations of the tlatoani’s authority to extract luxury resources from subordinate groups.3 The amantecas created these featherwork objects by cutting feathers into minuscule pieces and applying them to a blank surface with a natural adhesive in a similar technique to arranging mosaics.4 The feathers themselves were acquired by the pochtecas who traveled far distances into Central America to obtain them from the quetzal bird and other species not native to the Central Mexican Valley.5 As a result, featherwork objects, or amantecayotl, embodied the reach of the Aztec Empire, which wielded economic and political power over neighboring regions from which the feathers originated. The function of featherworks as an imperial signifier for the Aztecs would later be appropriated by the Spanish conquistadores who sought to convey their own imperial aspirations.

Beginning in the sixteenth century, Indigenous artists were commissioned by the Spanish clergy and colonial elites to depict Catholic imagery using the featherwork medium, thereby resulting in the creation of complex objects situated between different cultural systems of representation. While featherworks bearing religious imagery have commonly been interpreted as signs of European domination of the Mexica, the Spanish appropriation of a traditional indigenous medium for their most sacred works of devotional art speaks to a more nuanced relationship of power.6 In this reading of the featherworks, we can identify a system of artistic representation and symbolic meaning which would not be completely erased even in the face of Spanish conquest and conversion. Although the Spaniards chose to preserve the medium of featherwork and appropriate it for their own devotional arts, we can consider the skillfulness of Indigenous artists, the adaptability of Catholic images, and the dual coding of indigenous and European meaning as primary reasons why featherwork endured.7

The reception of featherworks from New Spain in Europe determined the impact they would have on the artistic practice and discourse of the Counter-Reformation as an era of stylistic transformation. The bewilderment that ensued upon the arrival of featherworks highlights the intensity of responses that these objects elicited.8 Created in Michoacán by the Indigenous artist Juan Batista Cuiris at the end of the sixteenth century, the featherwork pendants Jesus at the Age of Twelve (fig. 2) and Weeping Virgin (fig. 3) embody the astonishing optical effects that fascinated European viewers. Both figures are encircled by a shimmering turquoise background of hummingbird feathers, which appear both blue and green due to the effect of light on the surface of the feather fragments.9 The sacred quality of these images is indebted to the medium, which, through the chromatic vibrations of hummingbird feathers, breathes life into the figures of the Virgin and Christ. Building on Brendan McMahon’s argument that the “chromatic instability of colonial Mexican featherwork” transformed the visual experience of images in early modern Europe, we should reconsider their reception in the context of European stylistic developments.10 The green and blue hues of iridescent featherwork shift and change depending on the angle of both the viewer and the light source, and therefore they became enmeshed in artistic discourse about the affective capabilities of visual experience.11 In this way, featherwork images differed from the static medium of oil paint and entered into the vibrant debates surrounding the artistic imitation of nature and the wonders of the natural world. As such, the bewilderment of European viewers upon seeing Mexican featherworks can be explained not just by the objects’ embodiment of an exotic location, but by their connection to an intellectual discourse about “the illusory nature of the material world itself.”12

These decolonial reconsiderations about the reception of featherworks in early modern Europe share a concern for both the agency of the Indigenous artist whose skillful work captivated European audiences and the contributions of Latin America to intellectual discourse and artistic production across sixteenth-century Europe. The canon of early modern art should include objects like Batista Cuiris’s featherworks because of documented evidence that they were considered sophisticated art objects even by European artists themselves. In 1520, the German Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer traveled to Brussels to meet with Emperor Charles V regarding his pension. While in Brussels, Dürer saw the exhibition of Cortés’s gifts to Charles V, which included a large inventory of Aztec metalwork, textiles, and most likely featherwork.13 Upon viewing these objects, Dürer recorded in his journal: “I have never in my life seen anything that gave my heart such delight as these things for I saw in them the subtle ingeniousness of people in foreign lands. I cannot find words to describe all those things I found there.”14

This encounter between a Renaissance master and Aztec art is remarkable in and of itself, but the most significant aspect of Dürer’s testimony is his ascription of ingenium to the Indigenous artists of New Spain. Ingenium, or the innate quality of genius, was an early modern term attributed only to the most skilled painters, sculptors, and architects. Dürer’s inclusion of this terminology in his journal as he recalled the objects he saw that day demonstrates the affective power of New Spanish arts in the European imagination. Far from being described as exotic or primitive, the objects Cortés shipped back to the Holy Roman Empire were lauded as objects crafted by artists gifted with ingenium. However, it should be noted that while Dürer’s claim demonstrates that he perceived the makers of these objects quite differently than the dehumanizing conquistadores, it remains unclear how he viewed Indigenous artists in relation to himself, as the Aztec objects he witnessed may have fallen outside the bounds of a Renaissance definition of art, which privileged painting, sculpture, and graphic works.

Though Dürer’s Wing of a Blue Roller predates his trip to Brussels, it becomes impossible to view without imagining the influence of Aztec featherworks on the artist’s detailed description of the miraculously vibrant bird wing (fig. 4). Although there is no explicit evidence that Dürer ever drew the marvelous featherworks from New Spain that he experienced in Brussels, unpacking the social life of his Wing of a Blue Roller points to a likely linkage between the two art forms.15 Regardless, the interest in and relationship between featherworks and the hyper-realism of Dürer’s nature study helps us to imagine the ways in which arts from New Spain entered and impacted the intellectual discourse surrounding European art during the sixteenth century.

Wing of a Blue Roller was acquired by Emperor Rudolf II to be displayed in his Kunstkammer at Prague Castle, which also housed Juan Batista Cuiris’s featherwork pendants of the Virgin and Christ.16 As a great patron of the arts and sciences, Rudolf II was intensely interested in natural curiosities and what Brendan McMahon has described as contingent images, or “ambiguous pictures with unstable perception.”17 We can theorize that Rudolf paired Bautista Cuiris’s featherworks with Dürer’s watercolor not only because of their associations with birds, but also because they would have provoked humanistic discourse surrounding the capacity for art to imitate or even surpass nature.

The Kunstkammer of Rudolf II was organized into the dual categories of artificialia and naturalia, with man-made objects and items collected from nature being cataloged separately but not necessarily displayed in this manner.18 However, the featherwork’s natural medium, combined with human intellectual talent, disrupts the binary of Rudolf’s system of classification and therefore represents an object of exceptional curiosity. The natural medium of hummingbird feathers would have been understood by European viewers as secondary to the featherworks’ function as devotional works of art. Further, the astonishing optical effects of Bautista Cuiris’s featherworks could make even the hyper-naturalistic watercolor by Dürer appear mute and static. The hummingbird feathers’ chromatic instability combined with the breathtaking arrangement of color would have perhaps appealed more to Rudolf II who, in prefiguring the Baroque emphasis on the spectacular, was himself captivated by the wondrous things the world had to offer. Unlike the Renaissance, in which the most mesmerizing art was that which could imitate the ancients, the Counter-Reformation era ushered in a focus on affective, bewildering images that existed beyond the realm of intellectual or artistic explanation.

Isabel Yaya has demonstrated the desire amongst collectors to possess marvelous objects from the Americas and maintains that during the Counter-Reformation, “there was also a turning away from the classical standards of beauty towards an emphasis on the atypical work of nature and the abnormal.”19 The practice of collecting objects of exotica in the late sixteenth century aligned with the humanistic pursuit of compiling the macrocosm of the world within the microcosm of the Kunstkammer, yet also implicated the European elite in the process of American colonization.20 While featherworks indeed embodied the far-flung colony of New Spain, they also promoted the growing interest among collectors and connoisseurs in the marvelous, which would ultimately lead to the stylistic shift towards the spectacular image in the Baroque era.

In reaffirming the centrality of images to Catholic worship, the Council of Trent in 1563 and the later Counter-Reformation movement introduced the political valence of affect.21 Indeed, an entire genre of art rooted in the promotion of the sensuous as inherent to the practice of worship arose following the Council of Trent.22 The responses of bewilderment that followed the introduction of featherworks into Europe predate the profoundly sensuous devotional images of the Counter-Reformation, yet their reception by Dürer speaks to a longstanding impact. Claire Farago has theorized about the significant contributions of Latin American art to the intellectual landscape of Counter-Reformation Europe and argues that “non-European art may have contributed to the theoretical and critical discussions of western art, which never directly mentioned their existence.”23 Through documentary and visual evidence, the proposed thread linking featherworks to the emergent Baroque style of the Counter-Reformation has amplified the influence of Latin America and Indigenous artists on the stylistic transformation of European art.

Within the context of the Counter-Reformation, featherworks illustrated the power of spectacular images to captivate the viewer, as Europeans remarked upon the mesmerizing inexplicability of featherworks as objects of human artifice and marvels of the natural world. Predating the European Baroque movement by more than fifty years, featherworks breathed new life into the artistic and intellectual discourses surrounding the role of the image and the wonders of nature. Through this artistic influence, perhaps featherworks can be situated within an emergent Baroque aesthetic, which valued the marvelous, sensuous qualities so inherent to the affective capabilities of featherworks. Therefore, by crediting the Indigenous makers of featherworks as contributors to a period of European stylistic transformation, this paper has sought to reaffirm the active role of Indigenous Americans in the making and remaking of the visual culture of the early modern world.

____________________

Rachel Kline is a third-year PhD student in the History of Art & Architecture at Boston University specializing in the Italian Renaissance. With a background in anthropology, she hopes to use this perspective to explore the cultural meanings acquired by art objects and their materials circulating in the Renaissance. Rachel is especially interested in the artistic exchange between Italy and Northern Europe during the fifteenth century.

____________________

Footnotes

1. The shield was given by Hernán Cortés to the Bishop of Palencia, Don Pedro Ruiz de la Mota in his shipment sent from New Spain in 1522. Alessandra Russo, The Untranslatable Image: A Mestizo History of the Arts in New Spain, 1500–1600 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014), 28.

2. Alessandra Russo has suggested that for the Mexica people prior to Spanish conquest in the sixteenth century, featherworks were linked to the religious practice of sacrifice and the accompanying ritual performances. Alessandra Russo, “Recomposing the Image: Presents and Absents in the Mass of St. Gregory, Mexico-Tenochtitlan, 1539,” in Synergies: Creating Art in Joined Culture, eds. Manuela De Giorgi, Annette Hoffmann, Nicola Suthor (Florence: Kunsthistorisches Institut-Max Planck, 2012), 467. Additionally, Diane Fane has argued that the ways in which light and color interacted on the surface of the featherwork medium granted the chimalli an affective power. Diana Fane, “Feathers, Jade, Turquoise, and Gold,” in Images Take Flight: Feather Art in Mexico and Europe (1400–1700), eds. Alessandra Russo, Gerhard Wolf, and Diane Fane (Munich: Hirmer, 2015), 103.

3. See Alessandra Russo, "Cortes's Objects and the Idea of New Spain: Inventories as Spatial Narratives," Journal of the History of Collections 23, no. 2 (2011): 18.

4. Alessandra Russo, “A Contemporary Art from New Spain,” in Images Take Flight, 30.

5. The pochtecas were a class of long-distance merchants in pre-Hispanic Tenochtitlán who traveled as far as the southwestern United States and Central America to acquire precious goods for the imperial capital. See Deborah L. Nichols, “Farm to Market in the Aztec Imperial Economy,” in Rethinking the Aztec Economy, eds. Deborah L. Nichols, Frances F. Berdan, and Michael Ernst (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2017), 19–43.

6. Thomas Cummins has argued that featherworks depicting Catholic subject matter were primarily evidence of successful conversion of the Mexica by the Spanish. In reference to one of the first featherworks to be made with Catholic imagery, he maintains that “the feather painting of the Mass of Saint Gregory was thus intended as more than a material gift; it was an early sign of the conversion of the Mexicans, and proof that they were capable of a profound understanding of the mysteries of Christianity.” See Thomas Cummins, “To Serve Man: Pre-Columbian Art, Western Discourses of Idolatry, and Cannibalism,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 42 (2002): 116.

7. In Reframing the Renaissance, Claire Farago calls for a methodological approach to Renaissance art which considers the exterior factors of artistic influence and asks, “What would the history of the Renaissance look like if cultural interaction and exchange, and the conditions of reception, became our primary concern?” This type of decolonial methodology that aims to re-examine the visual culture of the Renaissance has informed my approach to the reception of featherworks in Counter-Reformation Europe. Claire J. Farago, “Introduction,” in Reframing the Renaissance: Visual Culture in Europe and Latin America, 1450–1650, ed. Claire Farago (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 8.

8. At the Debate of Valladolid (1550–1551), Bartolomé de Las Casas argued in support of the humanity of Indigenous Americans by citing their artistic capabilities. Las Casas articulated how the bewildering effect of featherworks convinced him of the rights of the Indigenous to sovereignty and even placed featherworks on the same level as contemporary European painting. In his Apologética Historia Sumaria he wrote: "But what certainly seems to exceed all human inventiveness, and which all the nations of the world will find not just curious but entirely novel, and all the more worthy of admiration and esteem, is the art that those Mexican people know how to make so perfectly, of creating with natural feathers with their own natural colors everything that they and all other excellent and first-rate painters are capable of painting with brushes." Bartolomé de Las Casas, Apologética Historia Sumaria, book III, LXII, 323–325, qtd. in Alessandra Russo, The Untranslatable Image, 85.

9. Feathers from the violetear hummingbird were increasingly used in featherworks postconquest because the species of bird was native to Mexico and the Spanish conquest had disrupted previous long-distance trade networks which imported feathers to Tenochtitlán from the rainforests of Central America. See Brendan C. McMahon, "Contingent Images: Looking Obliquely at Colonial Mexican Featherwork in Early Modern Europe," The Art Bulletin 103, no. 2 (2021): 29.

10. Brendan C. McMahon, "Contingent Images: Looking Obliquely at Colonial Mexican Featherwork in Early Modern Europe," The Art Bulletin 103, no. 2 (2021): 26.

11. McMahon, Contingent Images, 25.

12. McMahon, Contingent Images, 45.

13. Joseph Koerner, “Dürer in Motion,” in Dürer’s Journeys: Travels of a Renaissance Artist, eds. Susan Foister and Peter Brink (London: National Gallery, 2021), 44.

14. Albrecht Dürer qtd. in Koerner, “Dürer in Motion,” 44.

15. Anthropologist Arjun Appadurai has demonstrated that objects collect value and social meaning through human transactions. See Arjun Appadurai, “Introduction: Commodities and the Politics of Value,” in The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, ed. Arjun Appadurai (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 3–63. Alessandra Russo has argued that Dürer, who was intensely interested in nature studies as a way of obtaining knowledge, possibly created this watercolor in dialogue with the objects of Aztec art he saw in Brussels. See Alessandra Russo, “A Contemporary Art from New Spain,” 50.

16. Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann, “Remarks on the Collections of Rudolf II: The Kunstkammer as a Form of Representatio.” Art Journal 38, no. 1 (1978): 22–28; Alessandra Russo, “A Contemporary Art from New Spain,” 50.

17. McMahon, Contingent Images, 26.

18. DaCosta Kaufmann, “Remarks on the Collections of Rudolf II,” 24.

19. Isabel Yaya, “Wonders of America: The Curiosity Cabinet as a Site of Representation and Knowledge.” Journal of the History of Collections 20, no. 2 (November 1, 2008): 176.

20. Daniela Bleichmar, "Seeing the World in a Room: Looking at Exotica in Early Modern Collections," in Collecting Across Cultures: Material Exchanges in the Early Modern Atlantic World, eds. Daniela Bleichmar and Peter C. Mancall (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011), 15–30.

21. Between 1545 and 1563, the Council of Trent reevaluated the role of images in the Catholic Church in the wake of the Protestant Reformation, which had led to an outbreak of iconoclasm in Northern Europe. The Council of Trent resulted in the recognition by the Catholic Church that Protestants had renounced emotion and the senses in their practice of worship and so the Church could therefore use images that elicited an emotional response to appeal to followers lost to the Protestant movement. See Marcia B. Hall and Tracy Elizabeth Cooper, “Introduction,” in The Sensuous in the Counter-Reformation Church, eds. Marcia B. Hall and Tracy Elizabeth Cooper (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 2.

22. Hall and Cooper, “Introduction,” 2.

23. Farago, “Introduction,” 11.

“Taylor Davis Selects: Invisible Ground of Sympathy”

Institute of Contemporary Art / Boston

January 31, 2023–January 7, 2024

by Theodora Bocanegra Lang

What the deaf see is what seers hear.

A place of emptiness makes sense

to those of us who stand in the door.

– Fanny Howe, At Seaport: 2023 (2023)

The title of Invisible Ground of Sympathy, now open at the Institute of Contemporary Art / Boston, is taken from Taoism scholar Chang Chung-yuan’s (1907–1988) book Creativity and Taoism (1963), which describes the blending of the discrete subject and object through interactions. As Chang writes, “The dissolution of self and the interfusion among all individuals, which takes place upon entry into this realm of nonbeing, constitute the metaphysical structure of sympathy.” The single room of the exhibition acts as this realm of nonbeing, presenting a wide range of works with both obvious and opaque affinities (fig. 1).

Invisible Ground is curated by artist Taylor Davis (b. 1959), who selected works primarily from the museum’s permanent collection. Though Davis did not include her own sculpture, she placed five narrow and vertical copper-colored mirrors around the perimeter of the gallery. The mirrors reflect passersby onto the walls as they walk around the room, collapsing the spaces between works and visitors. This mingling is echoed in many of the works on view, such as Walking Camera (Jimmy the Camera/Gift to Jimmy from Laurie) (1987) by Laurie Simmons, a photograph of a camera with legs. By anthropomorphizing the art-making apparatus, Simmons locates artists, viewers, mediums, and objects in a nebulous conflation.

Interrogating these relationships further, Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Still #48 (1979) shows the back of a young woman with a suitcase, who is looking out from the side of a road. While Sherman (b. 1954) famously uses visual cues to trigger a cinematic narrative, here seemingly of an ingénue in trouble, the scene itself could be of a number of diverse situations. Interpretation of the work relies on something already present in the mind of the viewer to project meaning. This yields a communication that fuses artist, viewer, and effect, blurring boundaries between collective and individual reception.

Extending to considerations of physical reception, Wedges (2019) by Isabel Mallet (b. 1989) is a hammered chain of nine coins made from salvaged bolts. Works from this series can be used however the possessor decides: kept on a shelf, carried in a pocket, stashed under a couch cushion, or hung on a wall. The choice to install this work on a museum wall offers a specific viewing experience. Like Davis’s mirrors, they bring the conditions of observation and the room into the work.

The exhibition probes the room as seen by the visitor’s vantage point, as articulated by poet Fanny Howe in a text commissioned for the exhibition (excerpted above). By centering viewpoint and personal experience, Howe emphasizes the individuality of looking. The inclusion of Howe’s poem in the show also muddles categorizations of visual art: it is installed like an artwork on a low pedestal with a corresponding wall label and printed copies are available for visitors to take home.

Invisible Ground presents the viewer with an array of disparate works, each an opportunity for a different kind of communication. The gallery acts as a site of building bridges, highlighting connections and differences between subject and object and between viewer and art. Davis’s decision not to include her own sculptural work itself turns a mirror on all relationships present.

____________________

Theodora Bocanegra Lang is an MA candidate in Modern and Contemporary Art History at Columbia University. She received her BA from Oberlin College in Art History. She was most recently curatorial assistant at Dia Art Foundation, where she worked on exhibitions with Jo Baer, Joan Jonas, and Maren Hassinger.

Editors’ Introduction

by Sybil F. Joslyn

Affectation, the theme we have chosen for this issue of SEQUITUR, is at once relevant and expansive in its possibilities. In our present moment, as we still feel the effects of a global pandemic, international warfare, social justice uprisings, and climate threats, we as a people face a reckoning: who do we want to be, as a nation, as a community, and as individuals? What beliefs do we hold dear in our hearts, and in what capacity do we act? What aspects of our behavior are genuine, and which are performative, or rather, an embodiment of affectation? Centrally, these questions allude to a series of inherent dualities between interiority and exteriority, surface and depth, and artifice and core, and apply to topics inclusive of human behavior, materiality, and identity. It is these dualities and topics, in addition to its timeliness, that drove our excitement to call for material related to the theme of affectation.

Affectation has long been intertwined with the complexities of human self-presentation and artistic production. In behavior, appearance, or speech, it can refer to an intentionally exaggerated display, a manufactured artifice intended to deceive. In the history of art, architecture, and material culture, these impulses toward the artificial or hyperbolic might be employed by artists, practitioners, or makers to convey a certain message, meaning, or emotion. From the fanciful gestures of the Rococo to the simplicity of geometric abstraction, affectation defines the visual world we witness and the material world we navigate. In small objects and monumental structures alike, creators have manipulated materials, shapes, and formal qualities to curate a particular experience for the observer or user. Limited to appearances, the façade of affectation often masks motivations, identities, or truths that lie beneath the surface.

Another definition of affectation resists this binary and instead speaks intimately to the relationships between object and viewer, or between artwork and observer. An affective thing has an effect on something or someone, and thus affectation can refer to an object or work of art with a perceived influence or power. Over the last half century, scholars from the social sciences, folklore studies, and humanities disciplines have begun to critically study the capacity of objects to shape human behavior.1 In their links to functionality, religion, superstition, and status, objects and artworks are potent communicators and actors within the material networks of the human world. Whether they have inherent agency or gain agency due to human belief depends on your theoretical underpinning of choice, but a simple truth remains: objects and artworks have the power to move people, both physically and emotionally. Perhaps nowhere is this power more evident than in fields that prioritize the study of visual and material culture.

For instance, certain objects embody multiple facets of affectation, like a ship figurehead captured by F.W. Powell for the Index of American Design around 1938 (fig. 1). Likely dating to the late nineteenth century, the figurehead once adorned the prow of a fast-moving sailing ship, her left hand extended outward in front of her in the direction of the boat’s movement. Dressed in Grecian sandals and flowing chiton, she exemplifies figureheads of the neoclassical type that rose to popularity during the waning years of America’s Age of Sail. She appears every bit the classical goddess, the whiteness of her body and clothing carved in deep relief in imitation of the marble fine art sculpture that permeated visual culture on both sides of the Atlantic. Yet as Powell’s drawing shows us, these stylistic qualities are surface-deep; they comprise an affectation belied by cracks that have developed in her artifice, cracks that reveal the true character of the figurehead’s making. When we look closely at Powell’s drawing, chips in the figurehead’s paint and deformities in her surface allow her wooden materiality to become evident to the viewer, and weathered patches reveal pegs and joinery where her arm and cape have been attached to her greater form. This discrepancy between appearance and material nature is only one way in which the figurehead embodies our issue’s theme of affectation.

Figureheads, in their symbolic importance, also held a certain affective power for the crews of their respective ships. They were viewed as intimately tied to the context for which they were made, an embodiment of ship name, mission, and crew livelihood. Through their position on the prow, they were viewed as symbolic navigators and as the eyes of the ship, as guardians and protectors that would help ships find safe harbor at their destinations. Manifesting the superstitious lore of her maker and the seamen, the figurehead also held an apotropaic power to ward off disaster due to storm or threat in battle and to bring good omens if her form appealed to the personified sea. Akin to lucky charms, ship figureheads were a central component of shipbuilding during America’s Age of Sail and were believed to have held the power to affect the course of perilous journeys at sea. It is both aspects of affectation—artifice and affective power—that our seven authors engage with so beautifully in this issue of SEQUITUR.

Beginning our issue, Rachel Kline’s feature essay examines the facets of affectation present in the production and reception of Mexica amentecayotl, or feather pictures, in counter-reformation Europe. Crafted by Indigenous makers and featuring Catholic imagery, the material rarity and luminosity of these featherworks appealed to the tastes of cosmopolitan European consumers who favored transcendent artistic images in line with the burgeoning drama of the Baroque. Employing a primarily decolonial lens, Kline’s essay illuminates the affective power of materials and images while emphasizing the active and singular role Indigenous craftspeople played in the development of European collecting and style. Theodora Bocanegra Lang’s exhibition review of Taylor Davis Selects: Invisible Ground of Sympathy, currently on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art / Boston, creates a meaningful dialogue with Kline’s essay. Identifying the exhibition as a contrasting collection of objects, Lang expounds upon the affective power of each of its elements. In highlighting the connections between artworks and exhibition, artworks and collection, and artworks and visitor, Lang clarifies how the elements communicate and build a bridge between viewer and art and characterizes the viewer experience as one existing between the realms of nonbeing and objecthood. While varying drastically in time period and media, both Kline and Lang address how affective power forges relationships between people and art objects.

Three of our authors take a different approach to the theme and examine affectation as a manifestation of self-fashioning or self-presentation. Through a close stylistic and contextual analysis of Sofinisba Anguissila’s Self Portrait with Madonna and Child, Emma Lazerson discusses in her feature essay the ways in which the artist displayed two modes of artistic performance and affectation in her work. By adopting contemporary conventions of courtly dress and performativity and by imitating the styles of revered artists in the embedded easel painting in her Self Portrait, Anguissila fashioned herself as both courtier and master as a preemptive gesture of belonging to a group that had yet to accept her. Michaela Peine similarly addresses the themes of affectation and self-presentation in her research spotlight but does so through an analysis of “hidden” or obscured photographic self-portraits by Jo Spence and Mary Sibande. By examining select works, Peine explores the ways each artist constructed or modified identities to present to the viewer. In this way, both Spence and Sibande embrace the multifaceted nature of identity and adopt affectation as a possible valence of the self. Rounding out this discussion of connections between affectation and identity is Ateret Sultan-Reisler, who in her exhibition review addresses the nuanced message of Philip Guston Now, a retrospective of the artist’s work that was on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston last year. Concerned primarily with providing previously minimized historical and biographical context to his work, the exhibition illuminates for the viewer connections between Guston’s lived experience and the affectation of his expressive, abstracted style. Ultimately, Sultan-Reisler tells us, Guston’s turn away from figuration to abstraction, and back to figuration, can be viewed as an artistic response to societal oppression.

Finally, two of our contributors address affectation as a symbolic manifestation of the self. In his feature essay, Samuel Love traces artistic fascination with the affected visage of the commedia dell'arte archetype of Pierrot from the turn of the twentieth century through the 1980s. By analyzing the origins of anxiety provoked by coulrophobia, or a fear of clowns, Love identifies the ways in which alternative artistic communities from the Decadents through performers of Glam Rock identified with and adopted the Pierrot mask in recognition of their marginalized status. Concluding our issue, Isabella Dobson summarizes the events of Adornment, Boston University’s Mary L. Cornille (GRS’87) 39th Annual Graduate Symposium in the History of Art & Architecture, held for the first time in person since 2019. Organized by PhD students Hannah Jew and Rachel Kline, the Symposium featured seven graduate students who presented work in two panels, “Adornment, Power, and the Collective” and “Adornment, Identity, and the Body.” Reflecting on the theme, Keynote speaker Dr. Jill Burke introduced the argument of her upcoming book, How to Be a Renaissance Woman: The Untold History of Beauty and Female Creativity, in which she makes a compelling argument that female practices of adornment during the Renaissance can be viewed as acts of empowerment and agency. While the graduate speakers addressed a wide range of topics from Ancient Assyrian burial embellishments through Chinese export embroidery in the nineteenth-century, each showed how closely the themes of adornment and affectation are intertwined. Whether to convey power, communicate identity, or relate aspiration, artists and subjects throughout time have utilized objects with affective power and carefully cultivated their self-presentation for personal, political, and economic ends. Above all, the work presented at the Symposium has elucidated how central the study of adornment is to our understanding of visual and material culture.

It is with immense gratitude that the editors of this issue of SEQUITUR thank the authors for their contributions that so thoughtfully engage the theme of affectation. Addressing subjects from sixteenth-century featherworks through the counterculture of Europe’s twentieth, this collection of essays and reflections effectively grounds the abstract theme of affectation and demonstrates the fascinating possibilities its study can yield. It is our hope that this issue will not only provide an informative and intellectually stimulating respite from these challenging times, but that it will also prompt moments of introspection on the part of our readers. By turning the mirror on ourselves, we might use these discussions of inspiration, self-fashioning, power, and identity to consider how affectation has made us who we are and who we might become.

____________________

Sybil F. Joslyn is a PhD candidate in the History of Art & Architecture at Boston University. She studies American art and material culture in the long nineteenth century, and her research explores the intersection between material and visual culture, the expression of individual and national identities, and intercultural exchange in the Atlantic World. Previously, Sybil has held internships and fellowships at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Bard Graduate Center, Hirschl & Adler Galleries, Inc., and the Winter Show. Her dissertation examines maritime salvage as object, material, and process to interrogate perceptions of identity, property, and value during America’s Age of Sail.

____________________

Footnotes

1. Scholarly publications on object agency include: Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2005), 64–86; Daniel Miller, “Materiality: An Introduction,” in Materiality, ed. Daniel Miller (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005), 1–50; and Bill Brown, “Thing Theory,” Critical Inquiry 28, no. 1 (2001): 1–22.

Notes about Contributors

Isabella Dobson is a PhD student in the History of Art & Architecture at Boston University interested in the ways that eroticism, desire, and sensuality operate in paintings and prints of the female body from the Early Modern period.

Theodora Bocanegra Lang is an MA candidate in Modern and Contemporary Art History at Columbia University. She received her BA from Oberlin College in Art History. She was most recently curatorial assistant at Dia Art Foundation, where she worked on exhibitions with Jo Baer, Joan Jonas, and Maren Hassinger.

Sybil F. Joslyn is a PhD candidate in the History of Art & Architecture at Boston University. She studies American art and material culture in the long nineteenth century, and her research explores the intersection between material and visual culture, the expression of individual and national identities, and intercultural exchange in the Atlantic World. Previously, Sybil has held internships and fellowships at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Bard Graduate Center, Hirschl & Adler Galleries, Inc., and the Winter Show. Her dissertation examines maritime salvage as object, material, and process to interrogate perceptions of identity, property, and value during America’s Age of Sail.

Rachel Kline is a third-year PhD student in the History of Art & Architecture at Boston University specializing in the Italian Renaissance. With a background in anthropology, she hopes to use this perspective to explore the cultural meanings acquired by art objects and their materials circulating in the Renaissance. Rachel is especially interested in the artistic exchange between Italy and Northern Europe during the fifteenth century.

Emma Lazerson received her BA from Emory University in 2022 and is currently a first-year MA candidate in Art History at Case Western Reserve University. Her research focuses on early modern Italian female artists, contextualizing their practices in social, religious, and global theories.

Samuel Love is a PhD candidate in History of Art at the University of York. His thesis explores the carnivalesque visual culture of interwar British High Society, tracing how its engagements with baroque and Dionysian iconographies constituted a transgressive rejection of sociopolitical norms.

Michaela Peine received her BA in English and Studio Art from Hillsdale College, specializing in oil painting and portraiture. She is pursuing an MA at the University of St. Thomas studying Art History with a certificate in Museum Studies. She is currently researching contemporary artistic responses to Northern Renaissance and Baroque art, as well as decolonial educational practices in museums.

Ateret Sultan-Reisler is the John Wilmerding Intern in American Art at National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. She is working on a major retrospective of Elizabeth Catlett (2024–25). Ateret holds an MA in History of Art & Architecture from Boston University and a BA in Art History and Psychology from University of Maryland.

SIREN (some poetics)

Amant, Brooklyn, NY

September 15, 2022–March 5, 2023

by Farren Fei Yuan

The exhibition SIREN (some poetics) that was unveiled this fall at Amant in East Williamsburg, Brooklyn offers an evocative experience that dissolves the boundaries in sensory perception and artistic media. As such, it posits an alternative to the proliferation of Instagram-ready exhibitions that are focused on creating spectacles and repackaging works of art into reified commodity forms.

Founded in 2019 as a non-profit arts organization, Amant acts at once as a studio space for young artists and an exhibition space, aiming, most importantly, “to slow down the art-making process.”1 SIREN, for example, takes place in the multiple spaces of the gallery that spans across Maujer Street and envelops a courtyard garden. In contrast to exhibitions that simply present information to be received, visitors to Amant are led to make their own discoveries: inadvertently walking into the uncanny installation of a tire, an umbrella, and a school desk, or catching the sounds of bell chimes in the distance (figs. 1 and 2). These outdoor works embed poetics in the everyday.

SIREN is accompanied by a series of performances, poetry readings, “learnshops,” and creative writing workshops that take place during the exhibition period, in various spaces across the buildings. The ideas generated from these multi-disciplinary and open-ended activities become incorporated into one’s understanding of the artworks. SIREN takes place within a larger stream of everyday activities, meaning that the exhibition is “read,” “written,” and “narrated” even if it is also “seen.” SIREN encounters its audience on an individual level, through a private, slow, and multi-sensory experience. Visuality as the privileged mode of engaging with art is challenged by a range of activities that interpenetrate the gallery space.2

The dismantling of hierarchical categories of perception and knowledge has strong thematic resonance with SIREN. As Quinn Latimer writes, the siren which sounds “over land [and] across water” stands for both an emittance that establishes perceptual, linguistic, social, and territorial borders and as an expansive call that stretches across uneven terrains.3 This double-sided notion of drawing and erasing boundaries, at once disciplining and liberating, underpins the concerns of the works featured in the exhibition. The seventeen participating artists work freely in watercolor, drawings, textiles, sculptural installations, videos, and the written word, to interrogate the idea of the siren across domains and temporalities: as a figure of myths, songs, and poetry as well as of technology.

Lilian Lijn’s Queen of Hearts, Queen of Diamonds (1980), a pair of optical glass prisms whose three facets extend out through a tower of aluminum plates, are set apart, each emitting light that cuts across the space and interacts with the gallery lighting. Fetishized figures of patriarchal female archetypes and goddesses from Ancient Greek, Hindu, and Indigenous mythologies are dissipated into an assemblage of visual forms, texts, sound, volumes, and light that refuses to unify into an intelligible form. Their elusive bodies take the form of metallic pyramids under ample light (fig. 3) to flickering conical silhouettes in darkness (fig. 4), resisting capture by the objectifying gaze.

If Lijn works towards the dissolution of reified forms (both actual and figurative), other artists in the exhibition affront the visitor with sensoralities of the abject, thereby frustrating any attempt to spectacularize, reducing the exhibition into a pleasing yet inconsequential image. The most subtle example is a work by Patricia L. Boyd who has collected grease from restaurant leftovers, then used these materials to create negative casts of office items bought at a liquidation auction (fig. 5). The casts constitute a lexicon of rejects, the material evidence of the failures and excesses of contemporary society. However, these casts are embedded in the gallery walls, well above eye-level, such that their texture and form cannot be discerned. Boyd often works with “boundaries and thresholds”: the Borrowed Times series here introduces the abject (literally) into the institutional structure of the gallery and challenges the threshold of the visitor’s comfort.4

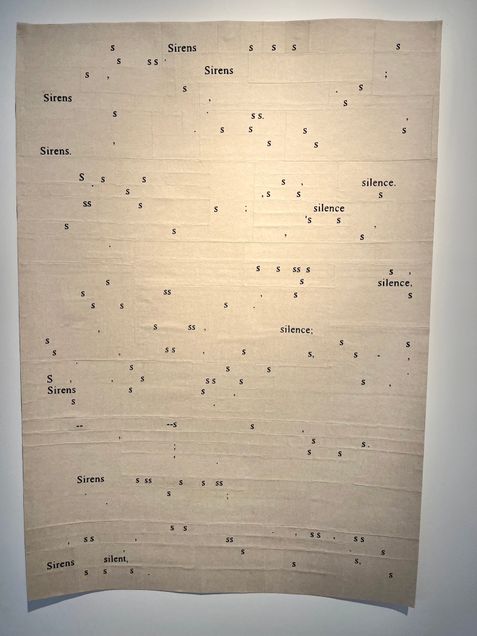

Such materiality of degeneration and decay is also palpable in Senga Nengudi’s R.S.V.P: Reverie-Combat Fatigue (1977/2011) in which hanging nylon stockings capture the material experience of the female body in its most deject, subversive state; or Nour Mobarak’s Fugue I and Fugue II (2019) where cultivated fungi cover two speakers whose multi-layered poetic recordings reflect upon history and memory (fig. 6). Addressing other dimensions of society, other artists in the exhibition turn moments of system failure into poetic allegories. Rivane Neuenschwander visualizes a possible glitch in communication in her textile piece, The Silence of the Sirens (2013) (fig. 7), a poetic constellation that emerges over a geometric grid, drifting between registers of sound and language: “silence,” “siren,” “SS,” “ssss(h).” The muted emptiness of the woven ground, and the refusal of the letters to give in to intelligible language, posit the mythical power of silence: as in Kafka’s parable referred to in the title, perhaps Odysseus survives because the sirens did not sing.

Making system failures visible exposes the problems and contradictions that would otherwise be simply smoothed over to produce an impression of successful operation. The artist collective Shanzhai Lyric, for example, composes poems out of counterfeit goods, consumer detritus, and theft practices (fig. 8). In Iris Touliatou’s HAPPINESS, 2018-2022 (to Laurie) (2022), a small display screen is held in place on a wall by the frame of an egg carton (fig. 9). Captions pop up at intervals, synchronized via a custom-made software to the speed of incoming notifications from the artist’s unread Gmail inbox. The continuous generation of signs that overflow in an incoherent narrative dramatically plays out the fracturing of today’s user-consumer’s sense of self. These are further played out on a phallic formal structure that is made uncanny by empty carton slots, the shadow cast on the wall, and the reflection of the viewer on the dark screen. The comfortably distant and secure position of the viewer that the spectacle relies on for its ideological functioning is disturbed.

SIREN posits the un-form, the abject, and the glitch as ways to practice contemporary poetics. The subversive power of the works is subtly embedded in their poetic beauty, like the deceptive charm of sirens, confronting the visitors and thereby resuscitating their experience. In a society of hyper-mediation, we need more exhibitions like SIREN which provoke us to reexamine and rethink common perceptions.

____________________

Farren Fei Yuan is an aspiring art researcher and critic. She graduated with a first class in BA in History of Art from The University of Oxford and is currently pursuing an MA in Modern and Contemporary Art: Critical and Curatorial Studies at Columbia University. Yuan has a special interest in image-text relations and post-war visual culture in the global context.

____________________

Footnotes

1. “About,” Amant, accessed December 10, 2022, https://www.amant.org/about.

2. This challenge to the assumptions underlying our conceptions of different activities is a strategy Rancière puts forth as an alternative to the rigidified practice of mixed media and interdisciplinarity. See Jacques Rancière, “The Emancipated Spectator,” in The Emancipated Spectator (London: Verso, 2021), 22.

3. Quinn Latimer, “SIREN (some poetics) [exh. guide],” Brooklyn, New York: Amant, 2022.

4. Patricia L. Boyd, “Contact Barrier: Patricia L. Boyd,” by Dora Budor, Mousse Magazine, July 5 2021, https://www.moussemagazine.it/magazine/patricia-l-boyd-dora-budor-2021/.

Following Institutional Critique Inside the Library

by Levi Sherman

When artists in the 1960s began challenging systemic authority, it seemed any cultural heritage institution—library, archive, or museum—could be a target of what would become known as Institutional Critique.1 The same period heard the first rumblings of today’s “digital convergence,”2 or the collapse of libraries, archives, and museums into repositories of information, accessed by users with little interest in the distinctions between these types of institutions.3 Yet even as librarians, archivists, and museum registrars blurred into “information professionals” in the 1960s, artists would develop a very different relationship with libraries than with archives and museums. My current research triangulates this unique artist-library relationship through the art historical framework of Institutional Critique, the cultural history of libraries, and the discourse of information science.

I hope to complicate the art historiography of Institutional Critique and glimpse what has been lost when the distinct purposes and practices of libraries, archives, and museums blur into information or institutionality writ large. These blurred boundaries haunt Institutional Critique from its inception in the journal October, which drew heavily from Foucault’s rather abstract understanding of the archive.4 It seems no coincidence that Henry Pisciotta writes from the perspective of a working librarian when he posits an alternative timeline of Institutional Critique, which peaks with the archival turn of the 1990s.5 Where art historians like Blake Stimson distinguish between a generation who tries to hold public institutions accountable and one who tries to redirect private institutions, Pisciotta shows that artists never stop trying to hold libraries to their mission.6

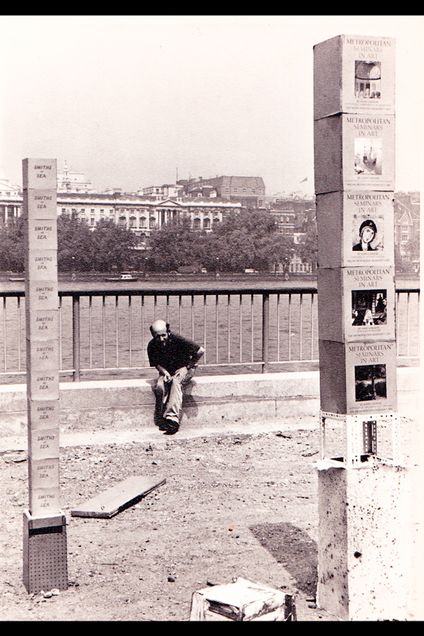

John Latham naturally figures into Pisciotta’s study of the Institutional Critique of libraries. Latham staged his spectacular book-burnings, Skoob Tower Ceremonies (1964–1968), at several institutional sites, like the British Library.7 Figure 1 illustrates another Skoob Tower Ceremony staged in London’s South Bank, with a similar civic architectural backdrop. But few later artists adopt Latham’s approach. Where Latham treats the library—like the museum and the courthouse—as a shallow signifier of culture and authority, later artists perform their critique from inside the institution, often with its permission and support.8 These artists understand the library as an exercise of authority but also democracy. They engage in a nuanced immanent critique that addresses how libraries operate rather than what they represent symbolically.

Beneath its stereotypically neoclassical façade, the modern public library has never been a centralized authority like the archive or museum, which share its spectacular architecture of power. Indeed, library history reveals continued frustration with this decentralized governance within national organizations like the American Library Association.9 Public libraries are accountable to taxpayers, serve amateur researchers, and prioritize information dissemination over preservation or connoisseurship. In other words, the anti-institutional pressure that Stimson associates with “new technologically enabled forms of peer-to-peer social organization” shaped the public library long before digital convergence began.10

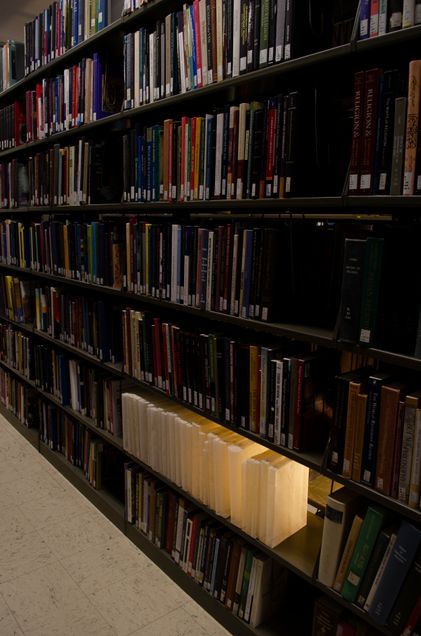

Artists need not intervene in the library’s spectacular trappings—its outward signifiers of culture and authority—because members of the community remain agonistically engaged with the institution’s inner workings. Indeed, the everyday interactions between the library and its patrons are generative points of departure for many artists. One example is India Johnson’s Negative Theology (2019–2020), which converses with a specific library as a site and set of practices (fig. 2).11 Johnson checked out a university library’s complete selection of books on the subject of negative theology and filled their spots on the shelves with fabric casts during the check-out period.12 Thus, the location, scale, and duration of Johnson’s installation are determined by the library’s classification scheme, acquisition plan, and checkout policy. Whereas Institutional Critique artists tended to approach art museums from the position of artists rather than patrons, Johnson's visit mirrors that of a typical user; anyone can remove books from a library shelf and keep them, thus altering the space within the constraints of the site.

Art history has been better at theorizing generalized modes of site specificity than addressing the operations of a specific site like a public library. My research seeks to understand how artists engage with libraries and their communities of readers by using the tools of library historians like Wayne Wiegand, a people's historian of libraries: the public and mundane evidence of policies, annual reports, meeting minutes, and letters to the editor.13 Reading Johnson’s immanent critique in the context of library history reveals the decentralized yet highly institutionalized terrain where people continue to encounter actual democracy, not just architectural and artistic spectacle of democracy found outside of the library.

____________________

Levi Sherman is a PhD student in Art History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. With a background in design and interdisciplinary art, he maintains a studio practice and co-operates a small press. Levi’s research interests include walking art, artists’ books, and the broader intersection of contemporary art, books, and libraries.

____________________

Footnotes

1. According to art historian Blake Stimson, “institutions were understood to be the means by which authority exercised itself” and so represented the system of “illegitimate authority” and control, which artists previously located in authoritarian figures like heads of state. Blake Stimson, “What Was Institutional Critique?” in Institutional Critique: An Anthology of Artists' Writings (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011), 22.

2. Wayne A. Wiegand, Part of Our Lives: A People’s History of the American Public Library (United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2015), 193–194.

3. Cecilia Salvatore, “Libraries, Archives, and Museums in the Twenty-First Century,” in Libraries, Archives, and Museums: An Introduction to Cultural Heritage Institutions Through the Ages (Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2021), 251–260.

4. In framing Institutional Critique, Benjamin H.D. Buchloh and Hal Foster tend to address the idea of the institution rather than its operation. Foster’s 1996 essay “The Archive without Museums” exemplifies this approach, which invokes the library as a Borgesian, Alexandrian thought experiment. Foster does so by blurring Foucault’s respective treatments of the library and the archive, which themselves tend toward the abstract. See Hal Foster, “The Archive without Museums,” October 77 (1996): 97–119.

5. Henry Pisciotta, “The Library in Art’s Crosshairs,” Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America 35, no. 1 (2016): 2–26.

6. Stimson,“What Was Institutional Critique?,” 37.

7. Elisa Kay, “John Latham,” Flash Art International 44, no. 280 (October 2011): 64–67.

8. Pisciotta discusses examples by Mel Chin, George LeGrady, Clegg & Guttman, and others which reveal different strategies for maintaining a critical edge while collaborating with the institution.

9. One telling example was the ALA “Library Bill of Rights,” which emerged during the Second World War to combat censorship and promote free inquiry. Library historian Wayne Wiegand notes that actually implementing the LBR was “almost always messy, often impossible, and professional consensus… was hard to discern.” Wayne A. Wiegand, Part of Our Lives: A People’s History of the American Public Library (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 166.

10. Stimson, “What Was Institutional Critique?,” 32.

11. India Johnson, “Negative Theology,” India Johnson, accessed October 18, 2022, https://indiajohnson.hotglue.me/?sitespecific/

12. Negative theology, or the study of the divine through what it is not, is no doubt a pun, but the subject also relates to Johnson’s research into the intersection of religion, language, and book art.

13. As municipally funded institutions with public boards, library records are generally more available than those at museums and other private institutions.

Curses as Crowd Control: Tourist Folklore at Pompeii

by Rowan Murry

In 1922, news of Howard Carter’s rediscovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb took the world by storm. In February 1923, excavators reburied and secured the tomb while archaeologists catalogued their findings and made plans for the next excavation season. It was around this time that the excavation’s financier, who had been present at the opening of the tomb, died mysteriously.1 In actuality, Lord George Herbert, the fifth Earl of Carnarvon (1866–1923), had contracted blood poisoning from an open wound caused by a mosquito bite.2 The press, seizing on the story of the Earl’s “mysterious” death, developed a sensationalized narrative of the so-called “mummy curse,” a legend that has pervaded the field of Egyptology ever since.3

The Egyptian mummy curse is an example of what I will refer to as “tourist folklore.” The term describes the perceived phenomenon of misfortune brought upon tourists who steal from or vandalize cultural heritage sites and the perpetuation of these myths by local inhabitants or stewards of these sites.4 Often, tourist folklore myths are bolstered, or sometimes even invented, by heritage site stewards to discourage theft or vandalism.5 This essay examines one example of how custodians of heritage sites manipulate public superstition to protect their sites from thievery and vandalism associated with tourism, especially in cases where funding and implementing physical security measures is impossible.

A valuable example of contemporary tourist folklore operates at the ruined city of Pompeii, an archaeological park near Naples, Italy (fig. 1). Pompeii is an important example not only because of its notoriety as a "dark tourist site"—a site associated with death and trauma—but also because it is one of the most visited UNESCO sites in the world, with approximately three million visitors per year.6 Using frameworks offered by Marcel Mauss and Michel Foucault, this essay utilizes the cultural heritage site of Pompeii as a means to explore the tourist folklore phenomenon. While the example of tourist folklore at Pompeii is not representative of all types of heritage sites and folklore, it provides an example through which to discuss themes of magic, dark tourism, and spectacle.

A discussion of the origins and function of tourist folklore requires an introduction to “contagion magic,” a dominant force fueling superstition and mysticism at Pompeii. The concept of magical contagion is best summarized by French sociologist Marcel Mauss in his book A General Theory of Magic:

The idea of magical continuity, realized through the relationship between parts and the whole or through accidental contact, involves the idea of contagion. Personal characteristics, illness, life, luck, every type of magical influx are all conceived as being transmitted along a sympathetic chain….However, magical contagion is not only an ideal which is limited to the invisible world. It may be concrete, material and in every way similar to physical contagion.7

In other words, once a person comes into physical or spiritual contact with an object, person, or entity, its essence, properties, or spiritual links are transmitted to the person. Contagion curses imply that the physical act of touching and subsequently removing an object from its home initiates spiritual contagion. The physical act of theft provokes bad luck caused by the object, the land, or a deity, which afflicts the offender and sometimes even their family and friends.

Pompeii shares similarities with the tourist folklore and mummy curses associated with the excavations of ancient Egyptian tombs. Anthropologist Anna Wieczorkiewicz dissects this societal fascination with ancient bodies and death, and concludes that “mummies, skulls, and skeletons become our fetishes in seeking meaning” about our own mortality.8 At Pompeii, visitors are immersed in a past world of paganism, debauchery, and destruction, where they play the roles of archaeologist, discoverer, adventurer, ancient Roman, and tourist.9 As a result, Pompeii becomes a dark tourist site where death and destruction are commodified and fetishized. This “quasi-religious mystique” of Pompeii is a crucial factor in a tourist’s decision to steal from the site.10 Visitors to dark tourist sites “seek tangible symbols of the place, the memory, meanings and experiences,” where material objects offer a medium through which they can reflect and channel complicated feelings or difficult memories.11 In addition to these motivations, I propose that the act of stealing artifacts from dark tourist sites like Pompeii is an act of defiance against mortality. It is a direct challenge to the destruction and death one must face at Pompeii—it gives the thief an illusion of control, both literal and metaphorical, over natural forces.

In October 2020, the media amplified the sensationalized story of a “cursed” Canadian woman who had visited Pompeii in 2005.12 She stole “two white mosaic tiles, two pieces of [amphorae], and a piece of ceramic wall” as souvenirs from her visit.13 In 2020, the woman returned the artifacts along with a letter, which stated that she “wanted to have a piece of history that couldn’t be bought,” and which she claims plagued her with bad luck and “negative energy” for 15 years.14 In the letter, she cites examples of her misfortune, including a breast cancer diagnosis and financial loss.15 She implies that the bad luck associated with the artifacts was the direct result of desecrating such a powerful site of trauma, loss, and destruction; it was a disrespectful act which activated Pompeii's magical contagion.

Luana Toniolo, Archaeological Officer of Pompeii, has estimated about 200 returns of stolen material to Pompeii over the past ten years, both resulting from and in anticipation of the potential curse.16 Toniolo suggested that artifacts which have been removed from their findspot lose their “strength as historical objects,” a quality which is crucial for the park’s mission of preservation and education.17 The park’s desire to deter tourists stealing and displacing artifacts led to a fascinating exhibition on the site’s tourist folklore. In response to the 2020 letter regarding the curse, curators at the Antiquarium of Pompeii compiled a temporary exhibition of letters and returned “cursed” objects. According to CNN, the purpose of the exhibition was anthropological, as a documentation of tourist interactions at Pompeii, but the underlying message is clear: do not steal from the site or else.18 News and media coverage of the alleged curses and subsequent exhibition further sensationalized the tourist folklore narrative maintained by the park’s staff.

The curse of Pompeii further perpetuates this air of mystique offered by dark tourism, and the stewards of Pompeii are using it to their advantage. By displaying returned cursed objects in the Antiquarium and in the media, the custodians of Pompeii are simultaneously creating further interest in the site while protecting it from future damage. The curse brings more visitors to the park, but the threat of magical contagion keeps them in line. At a place like Pompeii, which spans 170 acres, it is impossible to always surveil guests. This is where the curse plays a crucial role. In Foucault’s panopticon, a prisoner surveillance system which functions as a metaphor for modern society’s structure, the threat of constant visibility provokes self-regulation.19 At Pompeii, the threat of the curse plays the singular authoritative role which influences the behavior and social norms of the masses. Fear of this authority creates a system of self-discipline and social control—it is a means of surveillance without a physical entity.

At Pompeii, tourists’ desires to steal from the site stem from uncomfortable encounters with death, destruction, and dark tourism. The curse relies on its mystical associations with paganism and death at the site to both enrapture visitors and the media and ensure the site’s future protection from vandalism and theft. The media spectacle created by the curse serves Pompeii in various ways by preventing destruction and theft, serving as cost-effective security measures, and bringing more attention, visitors, and money to the site. In the face of mass tourism, curses can help communities and custodians regain some semblance of authority over their own heritage and history. However, in some cases, tourist folklore further perpetuates stereotypes and misrepresentations of ancient culture and beliefs. This is true for Pompeii, which is often portrayed in the media as debaucherous and esoteric. It is vital to consider the ways tourist folklore operates in different contexts and how this can positively or negatively impact our collective understanding of history and cultures.

____________________

Rowan Murry received her BA in Art History from the University of Mississippi and is currently pursuing an MA in Museum Studies at New York University. She is particularly interested in Ancient Roman art and archaeology, ethical collecting, and interactive technologies for physical and virtual exhibitions.

____________________

Footnotes

1. Mark R. Nelson, “The Mummy’s Curse: Historical Cohort Study,” British Medical Journal 325, no. 7378 (December 21–28, 2002): 1482.

2. Roger Luckhurst, The Mummy’s Curse: The True History of Dark Fantasy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 8.

3. Luckhurst, The Mummy’s Curse, 9; “George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon,” The British Museum, accessed December 12, 2022, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG53843.

4. Joyce D. Hammond, “The Tourist Folklore of Pele: Encounters with the Other” in Out of the Ordinary: Folklore and the Supernatural (Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, 1995), 159.

5. Other examples of sites that have a history of tourist folklore in order to discourage theft and vandalism include The Petrified Forest in Arizona and Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park.

6. The Palgrave Handbook of Dark Tourism Studies (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2018); “Visitor Data,” Pompeii Archaeological Park. This number does not account for any COVID-19 pandemic closures during 2020–2022. The most recent data comes from 2018.

7. Marcel Mauss, A General Theory of Magic (London: Routledge, 2001), 81–82.