Constructive Theology of Resurrection

Chris Smith

Women in the Word

INTRODUCTION: Some of you have met Chris Smith already in the preconference session yesterday, and some of you met her a number of years ago.

CHRIS SMITH: Hi, it’s great to be here. Again, I’m honored to have been invited to return to this event. I had a wonderful time a number of years ago, learned a lot, and was confronted by a couple of wonderful colleagues I was working with, and I’m appreciative to be back. And Christie, I want to thank you publically for your introduction of the way we really have tried as a threesome to think about the theme of this event. I appreciated your words a lot.

I want to do what Christie said. I want to spend my time really looking about some constructive theological work that I’ve been doing around the issue of resurrection, and so I’m going to take a plunge into that. Although before I do, I just want to say, there are two things on your table- one is a bibliography that’s just yours to take for your own information and for a resource for your preaching. The second is a poetic form that it would be good if you just got that in your hands, because there will be a moment where I will pause to use that. And interspersed with what I’ll be sharing, I’m going to use some slides and some images, and I would just like to say this. And I say it somewhat bashfully, although not too bashfully. I am not a visual artist. Many of you may be that, but I’m very intrigued and deeply appreciative of the visual arts, so I had some images that go with what I’m about to say. But a couple of weeks ago, I thought I just don’t have enough of the right images that I wanted. And so I set about taking some pictures from books. And so you’ve kind of caught me, or I’m right in the middle of developing a bit more explanation, and a bit more understanding of some of these images, but I’m going to use them somewhat ignorant of the full meaning of them, but hoping that they’ll be evocative for us.

In a time when systemic injustice, inflicted suffering, and human despair threatened to overwhelm us all, what are we as Christian preachers proclaiming about the power and possibility of resurrection in our contemporary lives?

How might our sermons more fully describe and evoke those moments in life when we see, feel, and experience the lived reality of God’s resurrection hope?

In the Christian community, we do affirm that Easter is the pinnacle celebration of our faith. The Christian Church remembers and celebrates an entire season called ‘Easter Tide-‘ those fifty days between the resurrection of Jesus and the coming of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost. At the heart of contemporary liturgical renewal is an effort to reclaim this season of Easter Tide, and an effort to focus more upon it as the focal point of our Christian life. Yet, even with renewed liturgical commitments to the resurrection, there are two contradictions that many preachers and communities of faith continue to perpetuate. First, even though we declare Easter to be at the heart of our faith, and at the soul of our Christian faith, many Christian traditions treat Easter Tide as a less important season than lent, I mean by far, that’s an understatement isn’t it? Of a great magnitude. Perhaps lent with the North American Christian Church’s primary focus on individualized and privatized sin, often. Also, during lent, the emphasis on sacrificial atonement theology, and individualistic spirituality often, maybe all that makes us feel much more comfortable than the deepest challenges of Easter faith. I wonder, why is there this contradiction in what we say is most important to us theologically and liturgically, and what actually captures most of our liturgical and theological attention. The second contradiction in the Christian Church for many of us has to do with the fact that we speak great affirmations about the power and possibilities of God’s resurrecting life, yet rather than embracing its power for our everyday lives, we relegate it exclusively to the mysterious and unknowable dimensions of life beyond this earthly reality, life after bodily death as we know it. Or we reduce it to what distinctively and exclusively happened to Jesus of Nazareth. In the face of all we affirm, why do we have this contradiction again? Why do many Christian people continue to understand the possibility and power of resurrection as that which is utterly unavailable to them in our daily lives? It’s my hope that the words that follow will move us to a greater theological and homoletical emphasis on resurrection in our preaching ministries that will provide significant alternatives to these two contradictions.

Preaching about Resurrection is Risky

Let us be clear though, that as we speak about resurrection that it is a risky thing. Resurrection life has everything to do with investing our lives, with committing our lives, with placing our lives in all those places where human beings suffer, and are oppressed, and in all those places where people yearn for new life. I believe that Christianity is about forming a people who take the power of resurrection life very seriously and move our bodies and our resources again into places that that power can bring about new life. Resurrection is again, not always the joyful and uncomplicated thing we’d like it to be. Let us be clear, that resurrection as the rising of the dead, or the dramatic vital life experienced on the other side of forms of death cannot be easily equated, as I think I did for years in the parish, with daily rebirth experiences. It’s not that those aren’t important, but somehow, it’s so linked with death, that’s is got to be a much more dramatic, theological understanding we have of resurrection than easily relating it to the earth’s reawakening, or to moment’s of rebirth for us, that may not be on the other side of death, even though they’re very important.

Resurrection is inseparably linked with crucifixions and with death, not in the traditional way the Church has often taught us, but in the lived reality of the people.

This is why perhaps the actual reality of resurrection is perhaps more terrifying than it is celebrative to us at points. During the season of lent, I sometimes think that if preachers and churches placed a greater emphasis on examining the social and political principalities and powers that crucify and violate people the world over, we would see churches more urgently and passionately turn to the good news of Easter faith. But we must be more willing to move more fully into the cost and risk of Holy Week with our lives in order to claim resurrection in new and powerful ways. Now let me just pause and say I’m not trying to suggest the kind of traditional theology that I’ve been taught, and many of us, maybe most of us have been taught our whole lives- that we have to have Good Friday in order to have Easter. I would want to speak against that theology. We need to work for a day, and resist in every way possible, as Christie has already pointed out, all those death-dealing crucifixions that happen in life. But I am saying that we must be willing to move into them in terms of solidarity and in terms of resistance if we are really to understand the full weight and the compelling force of resurrection.

I want to pause now and even though it would be easy to be rushed, I don’t want to rush. So I want to turn to you for a moment, and I want you to turn to yourself, and I want you to take that poetic form into your hands, and I want to invite you to create a poem about resurrection. It’s a simple poetic form- it’s a cinquain poetic form. It starts with a noun, then the two lines following it are adjectives following that noun, then the three words-I think of those three words as –ing (tape cuts out.) A poem of your own about resurrection. It could begin with the word resurrection, it could begin with any word. To each table, to turn toward your table members, and to share one poem at this time if someone’s willing at your table. No comments, just the hearing of the poem.

And deepen and even challenge some of the understandings and images we currently possess. These are my images, and I invite you to enter into them, and to generate in your own preaching ministries your own. There’s an image from my own life and community of faith of which I am a part that will begin our exploration. The first image of resurrection that I want to share as body of the risen Christ/ God’s hope for the new community. When I imagine what a Christian community striving to be the body of Christ looks like, I imagine my own home church Spirit of the Lakes United Church of Christ in Minneapolis, Minnesota. As a church community, it was birthed in 1988 as a church that would primarily serve and respond to the needs of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered people. The place of worship is a very large, bare kind of warehouse that has been transformed into holy space by all the hungers and hopes that people bring there. Often as you sit in worship, you can see people weeping. People are weeping sometimes out of deep personal loss, sometimes out of passionate connection to the hurts of the world, sometimes out of profound joy and celebration in the midst of the liturgy, and many times I think often, simply because gay men, lesbian women, bisexual and transgender people have never known the unity of Church, God, love, and sexuality all coming together in one place, and in the Church. There we sit as a community, holding each other’s longings, each other’s tears, and we seek to turn those tears into rivers of hope together. When we celebrate the Eucharist in Christina community, it has the power to constitute us, or reconstitute us as a people, and to help us literally become the body of the risen Christ. Each and every Sunday at Spirit of the Lakes we take communion. Each and every Sunday these individual Christian men and women who are so marginalized and oppressed by most religious communities around the globe, we stand in long processional lines leading to the communion table, waiting to partake of the bread of life, and the cup of blessing. Yet here is not a weeping or a feasting that is turned inward, but an act that is hopefully transformed to turns us outward to transformative action. These words are always spoken every single Sunday just before we commune:

“Each time we break this bread, we participate in the body of the risen Christ, for we are the body of the risen Christ. And each time we share the cup, we participate in God’s hope for the new community, for we are God’s hope for the new community.”

In these Eucharistic moments, the meaning and power of memory and remembrance takes on not only meaning for our present lives, but points at the eschatological dimensions for this meal as well. As we do these acts of remembering, we not only rehearse the life and ministry of Jesus, but we become a part of that Christic body that is able hopefully to breath new life into our world today. What does it mean to be the body of the risen Christ, or God’s hope for the new community? A couple of images. I have seven images of hope for the new community. This is a called ‘the nativity,’ and it’s from St. Paul the Apostles in Managua, Nicaragua.

And it’s, even though it’s a nativity depiction, there’s abundance there. There’s Oscar Romero, there’s Sandino in terms of the revolution, there’s lots of food, there’s abundance and a picture of a new community.

This is called, “The Birth of a New Man,” also a depiction from a mural in Nicaragua.

This is an image from the Philippines, and let me just read what the artist says about it.

“At the center is the figure of Mother Earth, holding an eye. In the iris of the eye, is a reflection of a child in the womb, a symbol of the future. The skull on which Mother Earth stands is death, which she has conquered. The colors used are those of the Philippine flag- red, white, and blue, with yellow for the sun and stars to suggest all kinds of historical and political meaning. On the right, weapons are converted into plowshares representing the nurturing of life, and the generations to come.”

Sorry, that’s so dark. If you look at, these next three slides are also from a church in Managua, and if you look at the overall mural, you see at the very center of it, as you can see, a crucified at the bottom, a kind of crucified people kind of imagine around the cross. I’ll zero in on that in just a moment. You get a resurrected image in that same mural. This is what is right above it, and is labeled, “The resurrecting Nicaraguan peasant.”

And finally, from Javanese, this is called, “The Birth.” And I was intrigued just by what it said about this depiction. It said that birth reflects new life and new hope. And in this particular community, the birth of a child is always seen as bringing new possibility into the world for a local community and for all the world. It’s not just that it brings joy to an individual family, but the child always symbolizes the hope for the new community. Lights please.

Resurrection As Process

The second image I want to share is resurrection as process, not moment. The Brazilian theologian Leonardo Boff invites us to consider that resurrection is not always that which happens in a dramatic moment, or that which happens suddenly, but rather it can be a process. He says,

“Wherever in mortal life goodness triumphs over the instincts of hatred, wherever one heart opens to another, wherever a righteous attitude it built and room is created for God, there the resurrection has begun.”

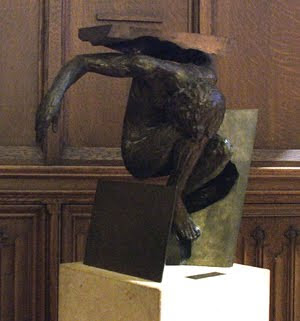

Boff’s words are powerfully true I think. We all know that work, the passion, the courage, the pain out of which resurrection life emerges. Instincts of hatred are locations of death, and they are unbelievably difficult to overcome, or it takes a lifetime, does it not, to nurture a heart that truly has the capacity to be open and changed by another. Or righteous attitudes and truths that one can stake one’s life upon are possible to find, but they are rare. We are instructed by Boff’s words, but perhaps the real hope lies in the affirmation that when these things happen in mortal life, there the resurrection has begun. Resurrection is a process, a turning, a striving, a stirring. Maybe it has as much to do with how we are moving through this world as where we end up. For Easter Sunday, in Imagining the Word, an arts and lectionary resources published by Pilgrim Press, there’s a piece of art entitled “Resurrection,” and here is the description of that sculpture. And we’ll see it in just a moment. “Art representing the crucifixion and the risen Christ is commonly seen. But art which attempts to present the moment of resurrection is rare. In a smaller than life representation, Paul Granlund has attempted to interpret just this moment. The figure of Christ is shown bent over, knees and head nearly touching. The arms are outstretched in a position of crucifixion. The figure is bound on three sides by the tomb, and on the fourth by the earth. Close examination reveal holes in the top an on the right side panel where the arm would have protruded when the panels were tightly closed around the body. The movement of the body is not downward, but upward and out. The outstretching of the arms and the propelling tension in the legs emphasize the surging strength of this Christ as the lid of this tomb is thrown off. The walls of death are not strong enough to prevail. Almost birdlike, this figure is breaking free, no longer under the sway of ordinary time and space. This is the power of resurrection.”

Boff’s words are powerfully true I think. We all know that work, the passion, the courage, the pain out of which resurrection life emerges. Instincts of hatred are locations of death, and they are unbelievably difficult to overcome, or it takes a lifetime, does it not, to nurture a heart that truly has the capacity to be open and changed by another. Or righteous attitudes and truths that one can stake one’s life upon are possible to find, but they are rare. We are instructed by Boff’s words, but perhaps the real hope lies in the affirmation that when these things happen in mortal life, there the resurrection has begun. Resurrection is a process, a turning, a striving, a stirring. Maybe it has as much to do with how we are moving through this world as where we end up. For Easter Sunday, in Imagining the Word, an arts and lectionary resources published by Pilgrim Press, there’s a piece of art entitled “Resurrection,” and here is the description of that sculpture. And we’ll see it in just a moment. “Art representing the crucifixion and the risen Christ is commonly seen. But art which attempts to present the moment of resurrection is rare. In a smaller than life representation, Paul Granlund has attempted to interpret just this moment. The figure of Christ is shown bent over, knees and head nearly touching. The arms are outstretched in a position of crucifixion. The figure is bound on three sides by the tomb, and on the fourth by the earth. Close examination reveal holes in the top an on the right side panel where the arm would have protruded when the panels were tightly closed around the body. The movement of the body is not downward, but upward and out. The outstretching of the arms and the propelling tension in the legs emphasize the surging strength of this Christ as the lid of this tomb is thrown off. The walls of death are not strong enough to prevail. Almost birdlike, this figure is breaking free, no longer under the sway of ordinary time and space. This is the power of resurrection.”

Can we as preachers nurture the kind of keen, homoletical lens as to adequately describe and proclaim the moments, the subtle movements and processes of resurrection- no matter how small, no matter how lengthy, no matter how gradual?

Lights, please.

Resurrection as Neighborhood/Community Transformation

The third image of resurrection is resurrection as neighborhood/community transformation. Just as the body of the risen Christ describes a powerful communal image of resurrection, so does the transformation of neighborhood and community. Resurrection does not just happen to isolated individuals; it happens to entire communities of people. Sometimes I think it happens to whole nations. It is surely what happened to the early followers of Jesus on the other side of his death and resurrection, as they moved from places of fear and silence, into a body of resurrected power and mission that would become a Church. Feminist scholars in the past two decades have been shifting Christological discussions from a sole focus on Jesus as the Christ to the community as the locus of redemptive salvific activity. From individual images of salvation to more communal ones. This is a welcome corrective, I think, to Christological discussions that would relegate salvific activity to individual acts alone. This same kind of theological work needs to be done I think in relation to resurrection. Because the Christian Church continues to exist in that United States and in Canada, in the midst often of alienating and disempowering western individualism, preachers need to name and proclaim more collective images of resurrection that renew our hope in community, and hold us accountable one to the other.

In 1993, I visited a Roman Catholic Parish in downtown Los Angeles. The Priest told a group of practical theologians from around the country about a group of Hispanic women who lived in that poor and violent neighborhood and who were transforming it. For months and years they had watched their children being shot down in the streets, murdered in front of their very own homes. They decided it was time to turn their neighborhood around. They moved their bodies with steady power into places that would make a difference. I think they decided to raise up new life instead of death. They organized together and began to face the drug dealers, the racist police, and the gang leaders who were killing their sons and daughters. They came onto the streets in the groups of 2 and 3 when drug deals were taking place, and they stood there, and they stood there and they stood there, until the drug dealers left. They marched to the police station and asked the police over and over again, ‘will you please tell us why you are killing our children?’ They organized barbeques and invited gang leaders to come and talk. And over time, the fidelity of those women transformed the entire neighborhood.

Perhaps resurrection has everything to do with placing our bodies someplace concretely and strategically and carefully and passionately figuring out what kind of transformation is needed where we live and in this moment in history. We do not infuse places of death though, with resurrection life by ourselves. Nor do we raise up whole neighborhoods. We do that in community. When God’s people throughout the ages, I think, have taken their stand against injustice and oppression, and against the mighty powers of evil that would threaten to silence us all, I think our life is raised and renewed.

Resurrection as neighborhood and community transformation I think demands that we sink down our roots even deeper into the places where we live, and the places we can make a difference.

Can we inspire and encourage people in our local communities to turn their neighborhoods of alienation and violence of all difference kinds around? Can we preach in such a way that people will reclaim the Church from the strangle hold of affluence and privilege power and raise it up again to be a place of the toiling, working God among the masses? A few images. Four images of resurrection as neighborhood and community transformation.

1. This is a woman who often gets referred to as Mother Hale, who in Harlem decided that there were so many babies being affected by crack in her neighborhood, that she needed to take them in and raise them after they had been abandoned, and she is known to have raised, how many, somebody tell me. Really I have forgotten the figure- it’s astronomical. It’s hundreds of children. And her influence also kind of spread throughout her own neighborhood as people kind of took up their own resurrecting action in response to hers.

1. This is a woman who often gets referred to as Mother Hale, who in Harlem decided that there were so many babies being affected by crack in her neighborhood, that she needed to take them in and raise them after they had been abandoned, and she is known to have raised, how many, somebody tell me. Really I have forgotten the figure- it’s astronomical. It’s hundreds of children. And her influence also kind of spread throughout her own neighborhood as people kind of took up their own resurrecting action in response to hers.

2,3. The next two shots are from Bluefields in Nicaragua again after a hurricane hit there in 1988. And I just thought, sometimes resurrection as community transformation looks like pounding nails and going through rubble and rebuilding. And finally, a mural in Nicaragua simply entitled, “Building a New World with Hope and With Friendship.” Will you turn, and someone else at your table share a second poem?

4. A fourth image is resurrection as bodily integrity. Carter Hayward, in one of her many profound critiques of the Church’s complicity in forming and sustaining a culture that hates the body says:

“If we are to live with our feet on the ground, in touch with reality, we must help one another accept the fact that we who are Christian are heirs to a body despising, woman-fearing, sexually repressive religious tradition.” (amens.)

It almost feels cathartic to just hear her words. “If we are to live with our feet on the ground, in touch with reality, we must help one another accept the fact that we who are Christian are heirs to a body despising, woman-fearing, sexually repressive religious tradition.” In the face of a Church that still values, my own words now, the spiritual realities of life over the material, bodily realities of existence- again, Christie’s reference to the rational over the emotional, I mean all the dichotomies that we experience- it would be hard to deny the role that the Christian Church has played in alienating human beings in profound ways from their embodied existence. In the face of such alienation, surely resurrection is connected to bodily wholeness and integrity.

By bodily integrity, I am pointing the integration of our embodied existence, an integration that knows human beings are bodies, not just spirits that reside in bodies.

An integration that knows our bodies are finite, limited, and sacred.

An integration that believes that no particular body reflects what it means to be human, or normal or natural.

An integration that knows that mind, emotion, spirit, and body coexist together in human beings and can never be fundamentally separated.

An integration that affirms that all human beings, I mean all human beings reflect the image of God.

Melanie May, in her book about the body and resurrection, invites us into a world she has known and lived through her body. It is a world of death and resurrection. For May, the experience of bodily existence, being diagnosed with breast cancer, experiencing a near-death moment in hospital years ago, being diagnosed with manic depression, and dealing with the forces of death around coming out as a lesbian woman in the church, all those experiences have led her to a very distinct embodied perspective about resurrection. She describes the time in her life, when after years of suffering with severe depression, she was finally told the diagnosis of bi-polar. And I know, again- I’m thinking Christie of what you said- labels can be reductionistic and often can be violating- no question.

There are other times, it seems to me, that they might be liberating. She said, “At last, I was relieved. I was relieved amid all the grieving, the raging, and the relief this diagnosis, this naming has been a purifying fire. The burden of my sense of moral culpability has burned away along with the acidity of society’s judgment.” Here’s a woman who’s finally come to understand what her bodily experience is all about in a way that allowed to move beyond shame, beyond shame. She then goes on to describe the dramatic changes that have been occurring in her life on the other side of that diagnosis. She says,

“When I speak of presence now, I speak first and foremost, of my presence in my body. I live and think in my body, no longer alienated or abstracted as I have been most of my life. I delight in my body’s desires, I savor the pleasure of aromas, I honor what my body knows.”

All human beings need bodily integration, bodily wholeness, bodily integrity. When a woman suffering from anorexia believes and knows her body is acceptable and sacred and can eat again in a healthy manner, it must feel like resurrection. When a man who is blind knows that he does not have to be physically healed to be whole, it must feel like resurrection. When an older adult knows that speed, mobility, and bodily strength do not determine sacred worth, it must feel like resurrection. When the flashbacks stop, and night sweats cease, and the bodily ravages of Post-Traumatic Stress end, it must feel like resurrection. What kind of sermons might we preach if we took the human body seriously as a locus of resurrection possibility and power, what would have to change for us to first more powerfully proclaim the resurrecting message that all bodies and all people participate in the imago dei, the Image of God.

A few images. Lights please. I’m going to show these with no comment. (images shown, but no commentary is given.)

Resurrection as Refusing to Play Cards with the Jailer

The fifth image of resurrection is, it’s kind of awkward, but it will become clearer. Resurrection as a refusal to play cards with the jailer. Mitsuye Yamada is a woman who was born in Japan and raised in Seattle, Washington, until the beginning of World War II when her family was removed to a concentration camp in Idaho. Out of that ethnic and cultural violence, this poem arose: “Playing Cards with the Jailer.”

Playing Cards with the Jailer- Mitsuye Yamado

a brief metallic sound

jars

the quiet night air

hangs

in my ears.

I am playing cards with the jailer

who shifts his ample body in his chair

while I fix my smile on his cards

waiting.

my eyes unfocused on the floor

behind him where a set of keys spiderlike

begins to creep slowly across the room.

come on come on your play I say

to distract him I tap the table

wait.

with a wide gesture

he picks up the keys

hangs them back on the hook

yawns.

the inmates will keep trying

will keep trying

their collective minds pull the keys

only halfway across the room each time.

the world comes awake in the morning to a stupor.

my brown calloused hands guard two queens and an ace.

my polished pink nails shine in the almost light.

I have been playing cards with jailers for too many years.

Japanese Americans who had to play cards with the jailers of white America, during the second World War, know what it’s like to be at the mercy of the powerful for their daily existence. Conversely, these same Japanese Americans must feel like they are rising up as a resurrected people. As they not only refuse to beg for freedom and dignity at the hands of white Euro-Americans, but as they have organized to demand concrete material reparation for violence done- property and resources lost, and cultural degradation endured. Perhaps there has never been a stronger preaching voice exposing the kinds of death that comes with playing cards with the jailer than Martin Luther King Jr. This exposure happened throughout his preaching and speaking, yet one moment sticks out.

It was April 16, 1963 during the time he was serving one of his many jail sentences, that he crafted the famous Letter from the Birmingham City Jail. He wrote this letter to a group of clergy who had criticized his civil rights activity as unwise and untimely. Here are his words.

“We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor. It must be demanded by the oppressed. For years now I have heard the word ‘wait.’ It rings in the ear of every negro with a piercing familiarity. This wait has almost always meant, never. I guess it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say ‘wait.’ But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will, and drown your sisters and brothers at whim, when you have seen hate-filled policeman, curse, kick, brutalize, and even kill your black brothers and sisters with impunity, when you see the vast majority of your 20 million negro brothers and sisters smoldering in an airtight cage of poverty, in the midst of an affluent society, when you suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six-year-old daughter why she cannot go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on TV, when you are forever fighting a degenerating sense of ‘nobody-ness,’ then you will understand why we find if difficult to wait. There comes a time when the cup of endurance runs over, and men and women are no longer willing to be plunged into an abyss of injustice. I hope sirs, (all clergymen,) you can understand our legitimate and unavoidable impatience.”

Will our preaching ministries proclaim a subtle and blatant ‘wait,’ or will our words, our visions, our truth-telling, enable people to tolerate the cup of endurance no longer? As terrifying as it sometimes feels to those of us in power, oppressed and violated people must stop playing cards with the jailer if they are ever to know the power and possibility of resurrection, and as difficult as it is to face, each one of us must face where and when we become that jailer.

Lights please.

Rosa Parks- 1955.

March on Washington, 1963.

A child in Nicaragua, small and afraid, I’m sure, who took to the streets to protest the military invasion of his country and his neighborhood and died as a result of his protest.

Resurrection as Resistance and Insurrection

A sixth image. Resurrection as resistance and insurrection. Contemporary theologians and people of faith speak about resurrection and its relationship to resistance in a variety of ways. Some theologians just simply say resurrection is radical courage. When human beings face into the possibilities of death, and on behalf of justice and the alleviation of oppression, this is a part of God’s resurrecting power. Others say the resurrection is the final sense of insurrection for right and justice. Another says, but despite the betrayal of the revolution, and God knows the betrayal of Christ, we see happening again and again what we all need most, uprisings of life against the many forms of death. This is resurrection.

Near the end of the month of June each year, gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people and their allies celebrate a great uprising of life. In many U.S. cities, the end of June is the time to commemorate and celebrate an insurrection moment in that community’s life. The evening of June 29, 1969, police routinely raided as they always had- but what happened that night wasn’t routine- but the police routinely raided a Greenwich Village bar, the Stonewall Inn. This was a gay bar that was the target of police harassment and brutality for years. On that night in 1969, instead of the patrons quietly accepting the actions of the arresting officers, they fought back. In fact, the insurrection and the resistance lasted for days following that night. The rebellion surrounding the Stonewall Inn in 1969 is not to be romanticized- a lot of people were injured. It was a very frightening time. Yet, for the gay, lesbian, bi-sexual, transgendered community, it was an absolute experience of resurrection. There were many historical groups and actions taken before Stonewall that allowed this moment to be so transformative. And few people would disagree though, that this moment stands out as utterly distinct in the community’s life. One author says,

“Stonewall is emblematic. It is the emblematic event in modern lesbian and gay history. Stonewall has become synonymous over the years with gay resistance to oppression. The 1969 riots are now generally taken to mark the birth of the modern gay and lesbian political movement. As such, Stonewall has become an empowering symbol of global proportions.”

Insurrection, resurrection, resistance moments are filled with holy paradox. Almost always, the risks are very high and the costs are terrific. Yet, simultaneously, moments when people are resisting abuse, or resisting oppression and violence are refusing the threat of death in all kinds of resisting, insurrecting ways. Those moments can at least, they don’t always, become resurrection moments, but they often become moments in which resurrection life can be born. We can think about the Montgomery boycott of the mid-50s. We can name on and on insurrection moments of a people that feel like resurrection.

Lights please.

Again, this is a bit dark, but from a mural in Nicaragua of Fonseca and Sandino which are heroes of the Nicaraguan revolution.

During the industrial revolution, there were a group of weavers that Kathe Kollwitz, a very famous artist depicted. And these weavers rose up in resistance to the technology that was displacing them and taking their jobs. And they rose up, and she’s got a whole series of portrayals of their resistance. And none of them are pretty…somewhat control of their own lives and resisted the technology that was being foisted upon them, and tried to urge their country to continue to honor weaving as a traditional art and means of livelihood. “Never Again War.” “A Disability Activist.”

The seventh image is resurrection as coming out.

Heterosexism is one of the fundamental structures of our social reality. It is built upon the assumption that relationships between females and males have primary relational meaning, exclusive social sanction, and superior moral and ethical value. Lesbians and gay men are not simply made invisible in the social fabric of our communities; they are actively excluded, harassed, persecuted and killed. The relational and social values of gay men, lesbians, bisexual, and transgender people are not simply silenced; they are judged inferior, deviant, and sick. In the face of such persistent bodily, economic, spiritual, and ecclesiastical violence, coming out has everything to do with resistance and resurrection. In the play “Coming Out, Coming Home,” a young closeted gay man gives us a picture, a taste of what the process of resurrection and coming out feels like. He said,

“It was three nights before I mustered the courage to venture out. I borrowed my father’s car and drove downtown. It was winter, cold and windy, but even so, I parked some 5 blocks away from the bar. God forbid the car couldn’t start, and I’d have to explain getting it jumped near a gay bar. I braced myself, and I opened the door. A blast of warm air greeted me, and my glasses fogged over at once. As I pulled my glasses off to clean them, I heard the sound of music in the background, and as I looked across the room, I realized I knew something intimate about each and everyone there. And just by my being there, they knew something about me. That thing that I had hidden and run from, and denied, we shared our secrets in mass. Silently amidst the blaring music. (tapes goes silent) Lost family or tribe, I felt affirmed and good about myself. It wouldn’t have had to have been in a bar. It could have been anywhere. Anywhere that gay people were gathered together happy and at peace. It could have even been in a church, but it wasn’t.”

“After all the fear, lying and hiding, telling the truth is positively sacramental,” one author says. It is a rite of purification. Authenticity and an integrated sense of one’s identity are critical dimensions of human health and well-being. Coming out has the sacramental possibility of enabling lesbians and gay men, bisexual and transgender people to cast off guilt, shame, and self-loathing. This purging, this purifying, this casting-off, surely at moments is the salvific activity of resurrection life. Do the words and messages of our sermons keep people in alienated closets of lies and secrets? Or do our sermons help open those suffocating doors? What would it look like and sound like if preachers of the Christian Church were to claim the sights of coming out as sights of resurrection and places and moments of God’s salvific activity. It doesn’t mean that resurrection is always there on the other side of coming out, but where are you in your preaching? There’s a grave responsibility to enabling and inviting people to open those closet doors. There’s also a grave responsibility to inviting people to keep them closed. A couple of images. The lights can stay off, I just want to summarize the last two images.

An eighth image that I’ve been thinking a lot about is resurrection as remembrance and presence.

And I’ve been thinking about the names quilt as one incredible symbolic expression of what really does happen in terms of people being made present. Those who have gone before us being actively present in our midst, the names quilt seems to be one symbol of that. I also think about the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington D.C. We could name countless acts of remembrance that keep alive a presence. We can all bring to mind the quote about Archbishop Romero’s blood rising again in the people of El Salvador. That’s about remembrance and presence. And if you read anything about his life and about El Salvador, one author described it this way, he said, “Everywhere you go, in everyone’s home in El Salvador, there is a picture of Archbishop Romero. It may simply be a newspaper clipping that’s brown and dingy and old, but somewhere in every home, there’s a picture.” Now that is about resurrection as presence. A few images, are all related to the AIDS name quilt, and then a few images related to the Veterans Memorial in Washington. The Veteran’s words are an enormous proclamation about the power of remembrance to change us.

And finally, the last image is just what I call practicing resurrection.

Returning to Melanie May’s words for just a moment we read, she says,

“I practice resurrection amid the mysterious and often tragic mingling of grief and ecstasy, dying and rising, I practice, but I do not celebrate resurrection.”

May honors both the truth of our lives and the truth and complexity of resurrection with such honest words. Resurrection is an experience inseparably linked with death. Being the body of Christ can raise a people up into new life. It can also bring death into that same people’s lives. Coming out can be a burst of authentic life and resurrection; it can also bring abandonment and condemnation. Resurrection can fuel insurrection and the repression that follows sometimes can be swift and bloody. I think she urges us to think of it as a daily practice. That’s her primary image. And so I leave us with two images, both related to Mothers of the Disappeared. One in Managua from a mural, and one in Guatemala. I think these women throughout the globe who have gone to plazas and marched in city streets, with the names of their loved ones attached to their body. And they just keep coming and coming and coming and coming, knowing very well that their loved ones are probably dead, are practicing resurrection.

May these images challenge and inspire us in our proclamations of God’s word.

May these images lead us to claim and name every conceivable expression of resurrection life among us.

May we as preachers reimage resurrection boldly.

May we, and those we share life and ministry with, practice it faithfully and persistently.

Will you share one more poem at your table?

Gratitude for God’s resurrecting power among us.

Amen.