Incarceration and the Health of Populations.

Public health as an organized enterprise emerged from a concern with living conditions in the mid-nineteenth century. It was a beginning that foreshadowed public health’s long engagement with social forces that influence the health of populations. However, there is also a range of issues that public health has not engaged with as forcefully as it perhaps might, given the public health consequences of these issues. I have, in a previous Dean’s Note, commented on firearms and their impact on the health of the public. I see firearms as a preventable epidemic, and one that should, and can, be a part of the public health conversation as we aim to identify areas where we can have impact to improve population health. Here I write briefly about another such issue, overlooked in my estimation by public health relative to the impact it has on the health of the public: incarceration. While this is an issue that has resonance for population health worldwide, I limit these comments to the US, animated by the challenge this issue poses for health at home.

Public health as an organized enterprise emerged from a concern with living conditions in the mid-nineteenth century. It was a beginning that foreshadowed public health’s long engagement with social forces that influence the health of populations. However, there is also a range of issues that public health has not engaged with as forcefully as it perhaps might, given the public health consequences of these issues. I have, in a previous Dean’s Note, commented on firearms and their impact on the health of the public. I see firearms as a preventable epidemic, and one that should, and can, be a part of the public health conversation as we aim to identify areas where we can have impact to improve population health. Here I write briefly about another such issue, overlooked in my estimation by public health relative to the impact it has on the health of the public: incarceration. While this is an issue that has resonance for population health worldwide, I limit these comments to the US, animated by the challenge this issue poses for health at home.

In 2012, there were nearly 1.6 million prisoners in the US state and federal prison population [see figure 1]. The incarceration rate in the US (716 per 100,000 people) is higher than any other country in the world, and about five times higher than the median worldwide (144 per 100,000).

![[Figure 1] Source: http://sentencingproject.org/doc/publications/inc_Trends_in_Corrections_Fact_sheet.pdf](/sph/files/2015/03/figure1.png)

Source: http://sentencingproject.org/doc/publications/inc_Trends_in_Corrections_Fact_sheet.pdf

Why does the US have such astoundingly high incarceration rates? Instrumentally, much of the rise of the prison population in the US appears to be largely a result of the Rockefeller Drug Laws, implemented in 1973 in New York State, which targeted drug offenders and took root as a model for national policy. Indeed, the incarceration rate of drug offenders rose explosively over the following three decades, as did the proportion of drug-related prison commitments. Perhaps at a more foundational level, we have as a society accepted that incarceration and retribution are acceptable, maybe even desirable, parts of our armamentarium to deal with fears about violence, rather than choosing other alternative forms of punishment or conflict resolution that minimize the recourse to incarceration. The role of social norms, and how they may influence our broader health conversation, shall be the subject of another Dean’s Note.

Why should public health care about incarceration? There is, unfortunately, ample evidence that incarceration is associated with health of populations, both directly—that is, for those who are incarcerated—and indirectly, for their families and communities.

Starting with those who are incarcerated, and considering mass incarceration as a disease, Disability Adjusted Life Year (DALY) rate linked to incarceration is over double that attributed to other conditions commonly experienced in the general population. Much of this disability arises from the bars to civic resources and participation, including employment and social welfare benefits like housing and public assistance. Looking at specific exposures, prison enhances the transmission of infectious diseases, such as TB and viral hepatitis, given the cramped spaces, injection drug use, and unprotected sex endemic in incarceration populations. Annually, approximately 1 in 7 Americans with HIV/AIDS passes through the prison system, representing a convergence of increases in drug-related incarceration and the emergence of this blood-borne virus. Another convergence—that of incarceration and mental illness—is the cause of substantial morbidity and, in the case of suicides, mortality among those who are incarcerated. A review of the evidence suggests that the prevalence of mental illness among those incarcerated is substantially higher than estimates from community samples. While there is little question that adverse social experiences such as incarceration contribute to the onset of mental illness, the relationship between incarceration and mental illness reflects a complex confluence of the rising incarceration rate, paralleled by a decline in the population institutionalized for mental disorders [see figure 2].

![[Figure 2] Source: http://www.law.uchicago.edu/files/file/harcourt_institutionalization_final.pdf](/sph/files/2015/03/figure2.png)

Source: http://www.law.uchicago.edu/files/file/harcourt_institutionalization_final.pdf

This suggests that many individuals in need of mental health care are instead being diverted to our prison systems. Although prisoners are the only US citizens with a constitutional right to health care, they often face delays in access to care, restrictive medication formularies, a lack of acute care options, and understaffing of specialty care medical providers. Female prisoners face particular challenges in getting care that is timely and appropriate. Substance use disorders are, predictably, also quite high among those incarcerated, and of the estimated 70 percent to 85 percent of prisoners in need of treatment, only 10 percent receive such services.

The burden of physical and mental illness associated with incarceration, and the limited attention that we give these health issues among the incarcerated, unfortunately only scratches the surface of the health consequences of incarceration. Growing evidence shows that the consequences of incarceration extend well beyond those who are imprisoned. Families of the incarcerated also face intergenerational consequences of incarceration; children experience years of separation from parents and the attendant attachment and family fragmentation that arise. Capturing this effect succinctly, recent parental incarceration, for example, is associated with a 30 percent increase in infant mortality rate, with a stronger effect among black children than whites. My colleagues and I have recently shown in one of our papers that non-incarcerated residents of neighborhoods with high incarceration rates (compared to those with low concentrations) have a two- to three-fold odds of current or lifetime major depression and generalized anxiety disorder. This likely reflects a combination of the social strain of incarceration among families and a confluence of adverse social circumstances that contributed to incarceration in the first place, compounding the challenges faced by residents of these communities.

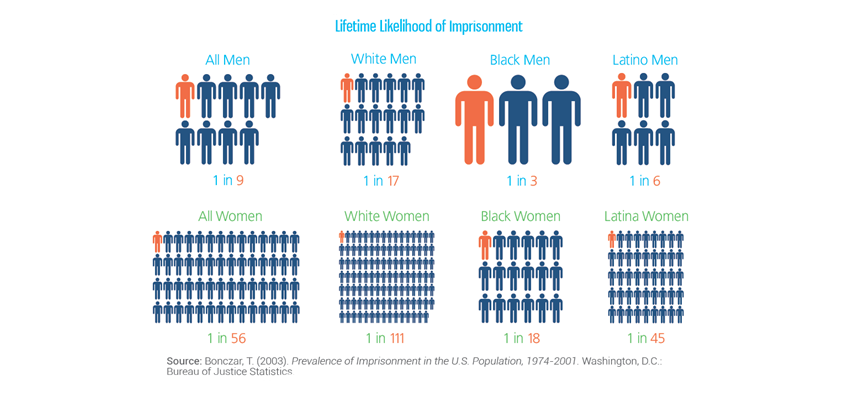

Separately, any discussion of the effects of incarceration must recognize that the burdens and consequences of incarceration are borne unevenly across US society, with minority populations being vastly and disproportionately affected by incarceration. Mass incarceration and its effects are wrought unequally on blacks and Hispanics [see figure 3]. To concertize this, among children born in 1990, 1 in 25 whites and 1 in 4 blacks had a parent imprisoned by age 14, an increase in magnitude and racial disparity compared with those born in 1978.

Source: http://sentencingproject.org/doc/publications/inc_Trends_in_Corrections_Fact_sheet.pdf

In a previous Dean’s Note, I commented on the health consequences of discrimination and will in future notes comment on the pervasive influence, as I see it, of racial/ethnic marginalization on population health in the US. However, for the purposes of this comment, I note that this extreme disproportion, by a factor of six among men, of black–white differences in incarceration represents a level of systematic marginalization and concentration of adversities faced by minority communities that represents on the biggest threats to the production of health throughout the country.

How do we then consider incarceration as a public health issue in a manner that can effectively mitigate its consequences? Emerging contributions to this area include a growing literature on the epidemiology of incarceration, including, centrally, an excellent book on the topic by Professor Ernest Drucker; some public writing about incarceration as a public health matter; and reports such as a recent Vera Institute report discussing the consequences of incarceration and how we can improve health in an era of mass incarceration. This is all positive and suggests that the tide may be turning—that the link between incarceration and public health is being made convincingly, inflecting a broader conversation. I worry, however, that the scientific and public conversation we are having thus far runs the risk of tacitly reinforcing the status quo, implying that if we could minimize the public health consequences of mass incarceration, our goal would be accomplished. A recognition, however, that incarceration represents a symptom of foundational social conditions that influence health in many other ways stands to guide us towards solutions—perhaps harder—that aim to target underlying structural conditions that create the health of populations. This echoes in some respects some of my earlier writing in a Dean’s Note on concerns with mechanisms vs. foundations and is a tension that I shall return to time and again in these notes.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Professor, Boston University School of Public Health

@sandrogalea