Athletics and Health.

As summer slowly fades and the fall comes upon us, I am spending an ever larger part of my weekends on the sidelines at my kids’ athletic activities, principally soccer. This got me thinking a bit about the role of athletics in health, particularly athletics played by youth across the US.

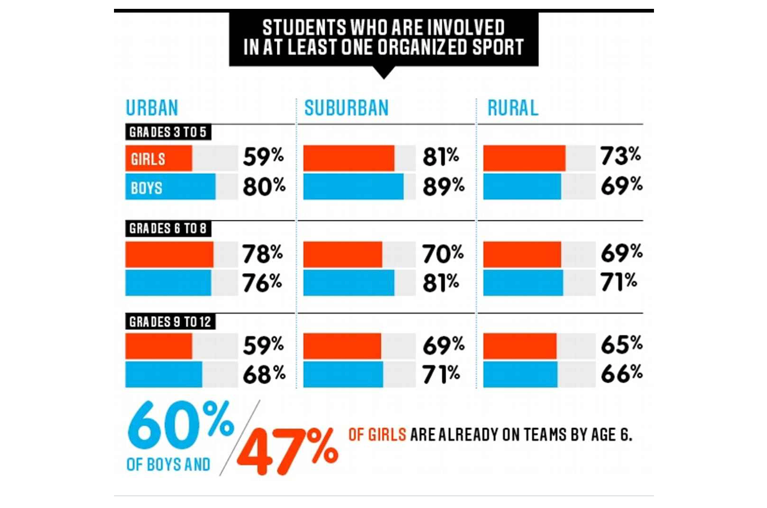

According to the Sports and Fitness Industry Association (SFIA), nearly 21.5 million American children between the ages of 6 and 17 play on a sports team (Figure 1).

Sixty percent of boys and 47 percent of girls are on teams by the age of 6—a total of 1.5 million children at any given time (Figure 2).

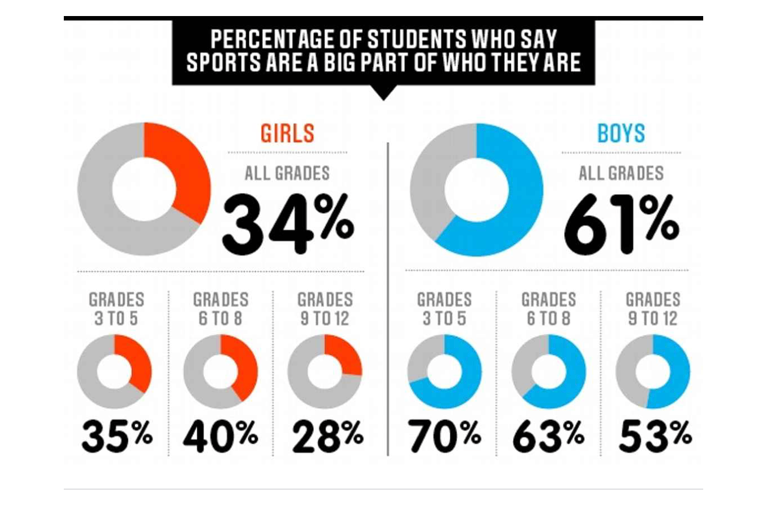

Sixty-one percent of boys and 34 percent of girls call sports “a big part of who they are” (Figure 3).

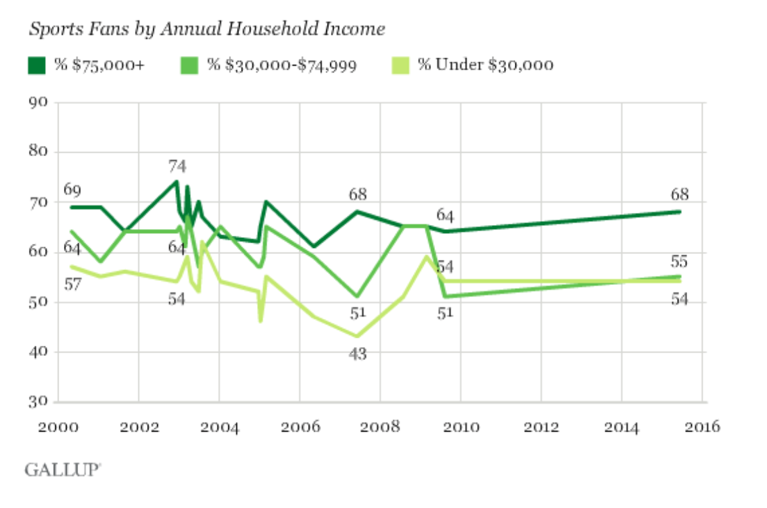

While few of these children will actually make a career in professional athletics, data indicate that many of them will likely remain interested in sports throughout life. A 2015 Gallup poll found that 59 percent of Americans say they are sports fans—66 percent of men and 51 percent of women. That proportion increases with household income. Sixty-eight percent of Americans who make more than $75,000 per year say they are sports fans; 55 percent of Americans making between $30,000 and $74,999 say the same, as do 54 percent of Americans making less than $30,000 per year (Figure 4).

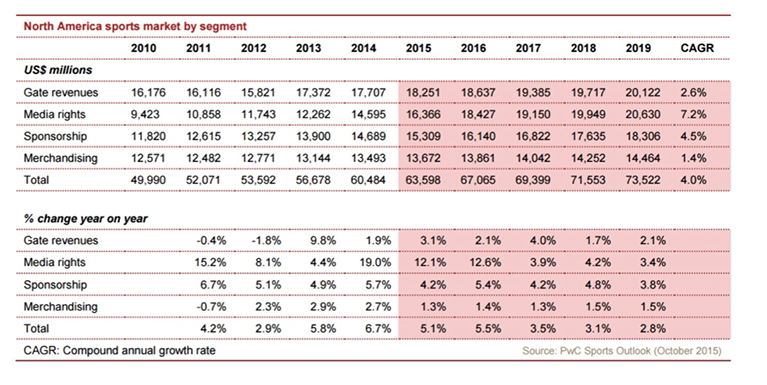

And sports are undeniably big business. The North American sports market is expected to reach $73.5 billion by 2019, with a vast empire of media, merchandising, and sponsorships revolving around the already robust revenue-generating capacity of the games themselves (Figure 5).

With all this investment of money, time, energy, and interest, it is apparent that sports are not merely recreation, but a cultural force. A note, then, on how this force influences health—in ways positive and negative—and how the sports world might be made more conducive to the well-being of athletes. A comment before I begin: Because much has been written recently about the connection between professional sports and health, I have chosen here to focus on athletics more broadly, seeing this as by far the commoner experience for our day-to-day lives. I do note, however, with pride, that scholars at Boston University, including several SPH faculty, are world leaders in this area, having published the seminal scholarship that in large part has put this issue on the country’s radar.

Clearly, there are extraordinarily important health benefits associated with sports. While elite athletes have been found to live longer than the general population, even moderate-intensity exercise has been linked to reduced all-cause mortality. Roughly 32 percent of American children and teenagers were overweight or obese between 2011 and 2012. In the context of the obesity epidemic, the popularity of youth sports is encouraging. It represents a chance for young people to develop an early enjoyment of exercise, with all the attendant mental and physical health benefits. These include a lower risk of metabolic and cardiovascular disease, and more control over weight gain. Because patterns of obesity begin early, sports can be an important form of prevention against the many hazards of the condition. Physical activity has also been positively linked to mental health and classroom success. A 2010 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention review of 50 studies found as many as 251 associations between physical activity and academic performance, and reported that the studies “suggest that physical activity can have an impact on cognitive skills and attitudes and academic behavior, all of which are important components of improved academic performance.”

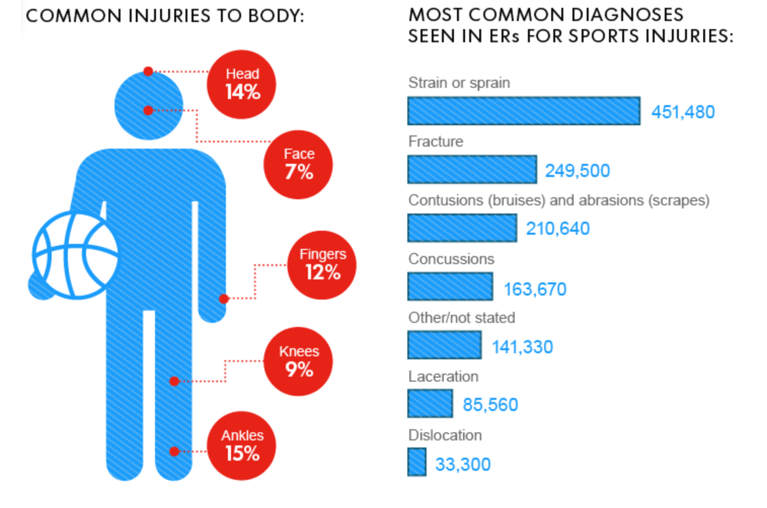

Despite these benefits, sports also have dangers. These include the problem of concussions and repeated “subconcussive” blows to the head that occur in high-contact sports like football and boxing. BU’s CTE Center has done much to advance our understanding of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, a progressive, degenerative condition that can arise as a result of repetitive brain trauma. Injuries—which can happen at the professional, collegiate, and amateur level—can also include musculoskeletal disorders, sprains, soft-tissue damage, whiplash, dislocations, and nasal fracture. Each sport has its unique hazards. Take field hockey, for example. The Datalys Center for Sports Injury Research and Prevention reports that there were more than 10,000 field hockey injuries on National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) member institution teams between the 2004–2005 and 2008–2009 seasons. Youth sports can also pose risks. According to the CDC, more than 2.6 million 0- to 19-year-olds are treated in emergency departments every year as a consequence of sports and recreation-related injuries. Common among these injuries are strains or sprains, fractures, and contusions (Figure 6).

It might be easy to dismiss injuries as simply an unavoidable pitfall of the vigorous, often combative nature of athletic competition. While it is true that all sports inevitably involve some measure of risk, it is also true that steps might be taken to mitigate that risk. Because so much of the athletics world is regulated, there are tremendous opportunities for coaches, administrators, and health professionals to collaborate towards the development of meaningful reforms. This happened in 2014, when these various interests came together under the auspices of the NCAA and the College Athletic Trainers’ Society to find ways to better safeguard the health of college football players. Together, they created guidelines that limit the number of live contact practices to two per week during the inseason, postseason, and bowl season, and four per week during the preseason. While these guidelines are not legislated rules, they do reflect the spirit in which greater steps might be taken, collaboratively, towards an athletic culture that values health as much as it values sportsmanship and success.

While some sports continue to be plagued by certain entrenched health risks—head injuries in football, for example, or the overall bloodiness of mixed martial arts—there is ample reason to hope that meaningful athletic reform is possible, for the good of player safety at all ages and skill levels. Consider the football reforms of the Progressive Era. Football, in the early 1900s, was shockingly dangerous. Protective equipment was scant, and the forward pass was illegal. To move the ball required raw strength and brutal maneuvering. Injuries and death were not uncommon among prep school players—there were 18 deaths and 159 serious injuries in 1904—and it became clear that the game was in crisis. Eventually, through the work of President Theodore Roosevelt and others, the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States (IAAUS) was formed—which would later be renamed the NCAA. The IAAUS changed the rules of football to make the game safer for players, easier for referees to control, and more accommodating of the physical limitations of participants. Reforms included shortening games from 70 to 60 minutes to minimize “fatigue injuries,” and legalization of the forward pass, eliminating the need for football to be played at rugby-like close quarters.

These reforms demonstrate the difference that comparatively small changes to a game can make in protecting the life and limb of players. As dangerous as sports can be, there are many risks currently faced by athletes that are unnecessary, correctable, and should be unacceptable. It is the work of public health scholarship to spotlight these risks, and the work of public health activism to ensure that they are properly mitigated, so that athletics may remain, on balance, among the healthiest of pursuits.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A. Knox Professor

Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Eric DelGizzo for his contribution to this Dean’s Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: https://www.bu.edu/sph/tag/deans-note/