On Knowledge and Values.

Before I start today’s note, a quick coda to last week’s Dean’s Note about obesity. A new World Health Organization technical report endorses soda taxes to reduce the spread of obesity, aligning well, to my mind, with the evidence that ultimately we shall need to change context, including behavioral incentives to drink or not to drink sugary soda, if we are to combat the obesity epidemic.

On to today’s note. There is an abundance of writing about the translation of science to practice. We have talked frequently about the core role of a school of public health in contributing to this translation process. Yet we are often confronted with the seeming immutability of some poor population health conditions. Obesity continues to rise. The opioid epidemic rages. And tens of thousands of people are killed by guns every year. Why? Why is there a gap between science and action? Why does science not always result in clearer action, particularly when we may have data suggesting how we may improve the health of populations?

I have come to feel that the core challenge of the evidence-to-practice gap rests around the intersection of two areas: our knowledge and our values, i.e., what we know and what we hold to be important. And that we need to have both clarity of evidence pointing to effective action and societal buy-In supporting that action in order for us to improve the health of populations. Our knowledge anchors our aspirations in the realm of the possible—what we can appreciably do at a given time, informed by what we know. Our values shape the direction we would like to go in as a community, the issues we would like to move forward; indeed, our priorities. While we are certainly able to act, and to succeed, without full knowledge, and while we have sometimes acted with imperfect knowledge when we have felt that the occasion required it, I would argue that public health is best able to point to solutions when we provide data that suggest clarity of action, and contribute to an environment where societal values are welcoming of these data. A Note, then, on striking the knowledge-values balance, to improve the health of populations.

How do we generate knowledge? What does it really mean to “know” something? A traditional approach to epistemology—the study of knowledge—holds that there are three components to knowledge: truth, belief, and justification. “Truth” simply means that, for something to be genuine knowledge, it must be true. This was famously expressed by Aristotle, in his Metaphysics: “To say of something which is that it is not, or to say of something which is not that it is, is false. However, to say of something which is that it is, or of something which is not that it is not, is true.” The importance of “belief” is fairly straightforward, as it would be contradictory to claim to both know something and not believe in it. “Justification” is less clear-cut. In Plato’s Theaetetus, Socrates considers that knowledge might be defined as “true belief with an account.” This is to say that knowledge is not merely belief in a true proposition; it is true belief that is supported by some kind of evidence, true belief that has been properly accounted for. This process of justification, of accounting for what we believe to be true, is a key function of our school and our scholarship. To say that we “know” something, within the context of our field, emerges from the work of many, through iterative research, writing, and debate. The scientific method and the rigor of peer review exist to provide a framework for this work of justification. Our tradition of discussion and argument—both among ourselves and through the structure of various fora—allows us to further refine what we know. This process is, by design, neither easy nor quick. Yet for us to call “knowledge” what may have started as an idea, a hunch, means we must engage with each step along the road from supposition, to proof, to, ultimately, consensus around a given issue.

What are values? What do we mean when we say we care about something? Values are what we choose to focus on, in a world of limited time and resources. This choice is both necessary—if we are to get anything done—and deeply revealing. Indeed, the philosopher José Ortega y Gasset once wrote, “Tell me to what you pay attention, and I will tell you who you are.” Normative ethics, the branch of ethics that assigns moral value to actions, puts forth three types of ethical theories to inform action: virtue, deontology, and consequentialism. Virtue ethics are concerned with the moral character of the person or people performing an action—i.e. are they good people acting in good faith? This means that, for an action to be ethical, it does not necessarily have to produce positive results, as long as it is performed by virtuous people. Deontology is concerned with the action itself—i.e. is it the right step to take? Is it being performed correctly? Under this system, intrinsically bad actions should be avoided, even if they may lead to positive results. Consequentialism is concerned with outcomes—i.e. what did this action, in the end, actually do? In all of these cases, values are defined by their relationship to what we do, and I have previously argued for a particular role for consequentialism in informing population health science. I argue for this, in part, because I see it as speaking to a fundamental truth about values—they tend to catalyze action. When we genuinely care about something, particularly when it is an injustice in need of correcting or a matter of lives to be saved, it is difficult to remain a spectator, or to limit our activities to the accumulation of knowledge for its own sake. Our values push us to mobilize our knowledge in pursuit of healthier populations, guiding our priorities towards the areas where we can best make a difference.

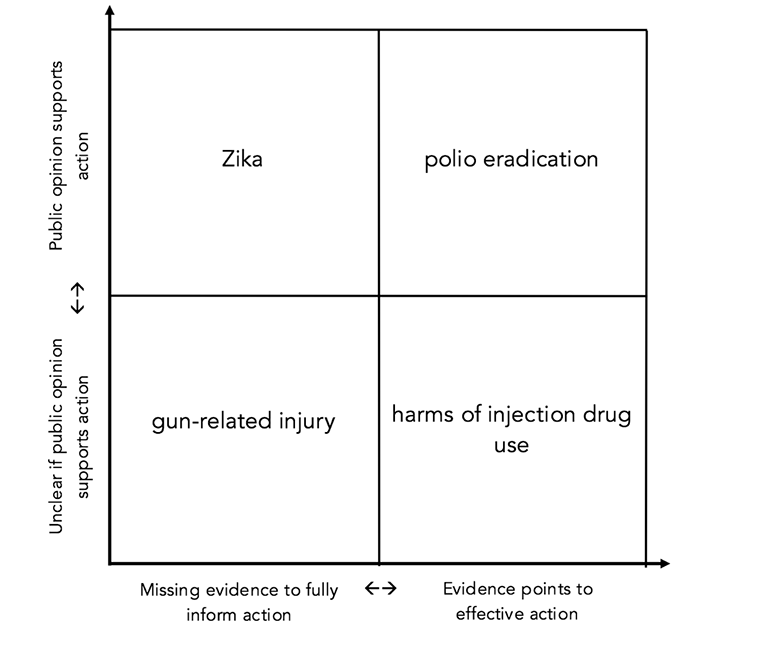

So, what of the intersection of knowledge and values? To illustrate the intersection, and occasional gulf, between our knowledge and our values, I would like to propose a 2-by-2 grid inspired by Donald Stokes and his Pasteur’s quadrant, which I cited in a previous note.

At the top right of the table are issues where we know what to do, and where public consensus, informed by values, is indeed aligned with action. At the bottom left, we encounter cases where the way forward is less clear, where our data are incomplete and our actions not yet bolstered by public opinion. In between, the table holds cases where we may have value-informed consensus on the need for action but little data to inform that action, and, vice versa, where we have our data in hand, but no clear mandate from the public to proceed with our efforts.

Four examples to illustrate this framework. At the confluence of knowledge and values is the worldwide fight against polio. In 2016, polio is on the brink of global eradication due to a combination of good data, well-tested methods, and the values-driven decision of governments and public health professionals to prioritize ending this terrible disease. Humanity’s long history with polio, and the epoch-changing development of a vaccine, has placed efforts against the disease in the strongest possible position for a public health intervention. Governments and NGOs have mobilized resources in order to wipe out polio, and the aims of the scientific community have dovetailed with the will of the public.

On the opposite end of the grid is the example of gun-related injury. Gun violence is a clear threat to public health—in the US there have been more than 8,000 gun deaths and over 17,000 gun-related injuries this year. However, our efforts to prevent this ongoing tragedy are not yet supported by sufficient data. Interest group success at blocking federal funding for gun violence research means that we do not yet know all we should about the epidemiology of this problem, hindering our attempts to move the issue forward. The gun lobby has also succeeded, far better than we have, at framing their case as a matter of values, whereas our efforts, while certainly motivated by our values, have been hindered by a lack of broad, organized public support.

Closer to the “knowledge” axis, we have the problem of injection drug use. Injection drug use poses health threats on multiple levels, including the possibility of addiction and overdose presented by the drugs themselves and the risk of diseases like Hepatitis and HIV associated with needle-sharing. We know that supervised injection sites and needle exchanges can go far towards mitigating these risks. However, despite the clear benefit of these measures, efforts to implement them have been slow to gain traction, due largely to the social stigma around this issue. As a result, our investment in these potentially lifesaving interventions has not been commensurate with the scale of the threat.

Finally, there is the challenge of Zika; an area where we have had to act decisively on our values of safeguarding population health, even as our knowledge of the disease remains in its adolescence. We are still learning about how Zika spreads, its origin, and how it can be stopped. Despite these unknowns, the danger of the virus means that we cannot delay our interventions until our knowledge is more fully formed. As best we can, we have taken action to prevent Zika using what we know, while working assiduously to learn what we do not.

We are in the business of safeguarding the health of populations. An appreciation of the dual role of knowledge and values in this regard suggests that we need to work on both axes: improving knowledge and influencing values. The more we know about a problem, the more options we are able to apply towards solving it. At the same time, that knowledge is unlikely to result in much action absent a broad, value-informed consensus on the need for action. That is in no small part why we, to my mind, have as a school articulated our broad aspirational common purpose as “Think. Teach. Do.”—because we shall not be meeting our goals without both generating knowledge (“thinking”) and acting to influence and inflect the public conversation (“doing”). It is my hope that what we do as a school rises to the challenge on both these axes.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A. Knox Professor

Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Eric DelGizzo and Catherine Ettman for their contributions to this Dean’s Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: https://www.bu.edu/sph/tag/deans-note/