Housing and the Health of the Public.

Housing is a foundational determinant of health, and has been recognized as such since the early days of public health. In the 19th century, outbreaks of infectious diseases sparked interest in housing reform to address poor sanitation, crowding, and inadequate ventilation. Moving rapidly to the present, the report of the WHO commission on the social determinants of health focused on the concept of “safe housing” as key to the health of populations. I have previously written about homelessness in this space, but today I wanted to focus, more fundamentally, on housing itself.

There are ample data connecting poor housing conditions to a broad range of infectious diseases, chronic diseases, injuries, childhood development, and nutrition issues, as well as to mental health. For example, substandard housing conditions such as poor ventilation, pest infestation, and water leaks are directly associated with the development and exacerbation of respiratory diseases such as asthma. There are about 24 million Americans with asthma, and it is the most common chronic disease in children worldwide. About 40 percent of diagnosed childhood asthma is attributed to exposures at home. Those living in poor housing are disproportionally people of low-income and people of color; it is not surprising then that the rate of asthma in black children is nearly two times higher than the rate of asthma in white children (Figure 1).

https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2014-05/documents/hd_aa_asthma.pdf Accessed January 25, 2017.

Other examples abound. Cases of lead poisoning—which affect the development of the nervous system—occur from home exposure, particularly in old houses with deteriorating paint, and among residents who cannot afford to repaint their houses. Additionally, 1 in 15 homes currently has elevated levels of radon—a natural radioactive gas which is associated with lung cancer. Unprotected windows, exposed heating sources, breakable window glass with poor lighting, lack of safety devices such as smoke detectors, and slippery surfaces are all linked to substandard housing, contributing to housing-related injuries. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Commission to Build a Healthier America estimates that every year, 4 million emergency-department visits and 70,000 hospital admissions are linked to injuries that occur at home. Other unfavorable housing conditions, such as crowding and homelessness, contribute to the spread of infectious diseases, tuberculosis in particular. Moreover, exposure to cold indoor temperatures is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular diseases. Finally, there is evidence that the quality of housing affects mental health. Children from crowded houses exhibit poorer cognitive and psychomotor development, and cold, damp, and moldy indoor conditions may be linked with anxiety and depression.

The role of housing as a powerful determinant of health is not confined to the spaces individuals call “home.” The link between housing and health is complex and includes influences across multiple levels, including the neighborhoods where people live, their families, and the individuals themselves. Figure 2 provides a framework to consider the impact of multi-level environmental exposures of housing conditions on health outcomes, using asthma as an example.

Rauh VA, Landrigan PJ, Claudio L. Housing and Health. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008; 1136(1): 276—288. doi:10.1196/annals.1425.032

At core, housing affordability, a persistent challenge in the US, shapes the physical conditions of houses themselves and the neighborhoods around homes. More than one-third of the population (39.8 million households) was cost-burdened (paying greater than 30 percent of their income on housing) in 2014. Among these households, about half (16.5 million) paid 50 percent or more of their income on shelter. Moreover, the number of cost-burdened renters continues to increase. In 2013, just under half of renters in the US were cost-burdened. By the end of 2016, the percentage of house ownership in the US continued to be low, at 63.5 percent. The fall in homeownership was largely driven by increases in housing prices, making buying prohibitive for many renters.

As housing costs rise, the number of households that need federal assistance to afford housing continues to grow every year. Data from the 2016 State of the Nation’s Housing report shows that only 1 in 4 eligible renters receives any type of assistance. The remaining renters look at the private market; however, the units affordable to lowest-income households are by this time usually already rented by higher-income households. Those who are not fortunate enough to receive government housing assistance are increasingly driven to homelessness. The US Conference of Mayors concluded that lack of affordable housing is the leading cause of homelessness.

It is important to note that the burden of poor housing is not distributed evenly across populations, but, rather, affects some groups much more than others. Families with fewer resources are more likely to live in unaffordable and unhealthy houses, and are less likely to be able to improve the condition of their homes. For example, living in unaffordable housing puts families and individuals in the position of having to trade between housing and other basic necessities such as food and adequate nutrition (Figure 3).

Housing Challenges. Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University website. http://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/jchs.harvard.edu/files/jchs-sonhr-2015-ch6.pdf Accessed January 25, 2017.

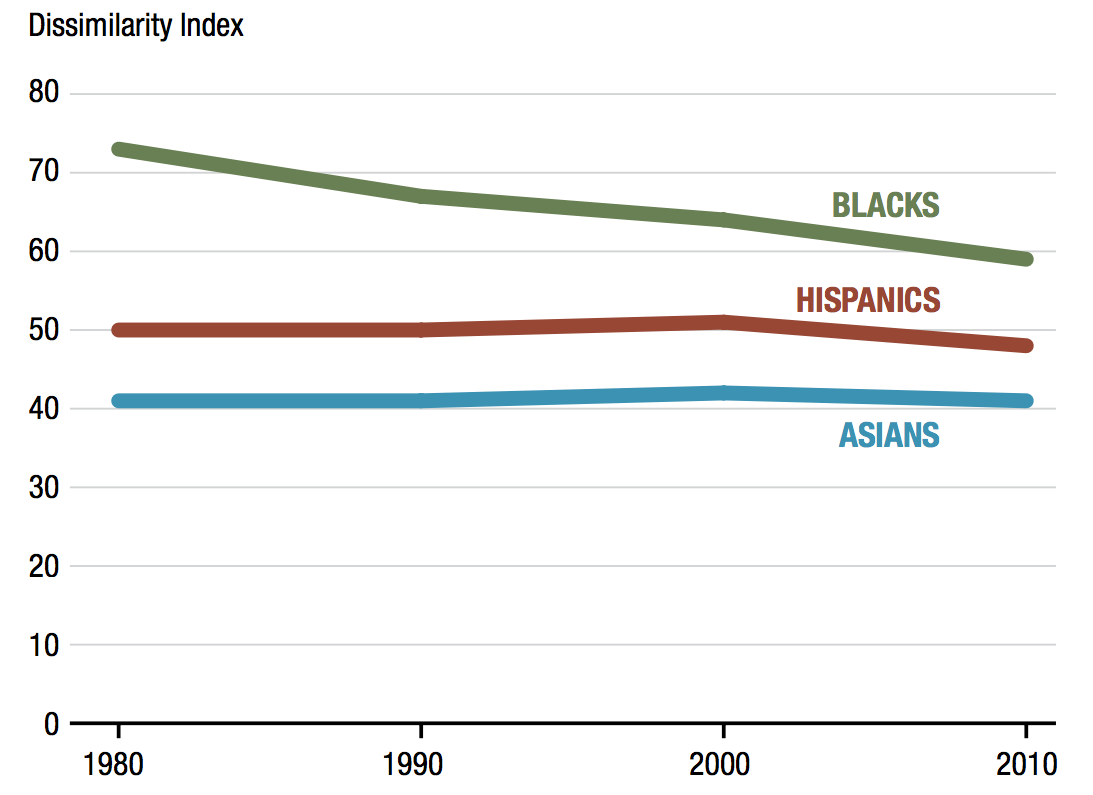

The forces of income segregation and racial/ethnic segregation have an enormous effect on housing suitability and health. In large metropolitan areas, the percentage of families living in “poor” or “rich” neighborhoods increased from 15 percent in 1970 to 34 percent in 2012. Moreover, disparities in housing based on racial background are substantial (Figure 4). Approximately 7.5 percent of non-Hispanic blacks and 2.8 percent of whites live in substandard housing.

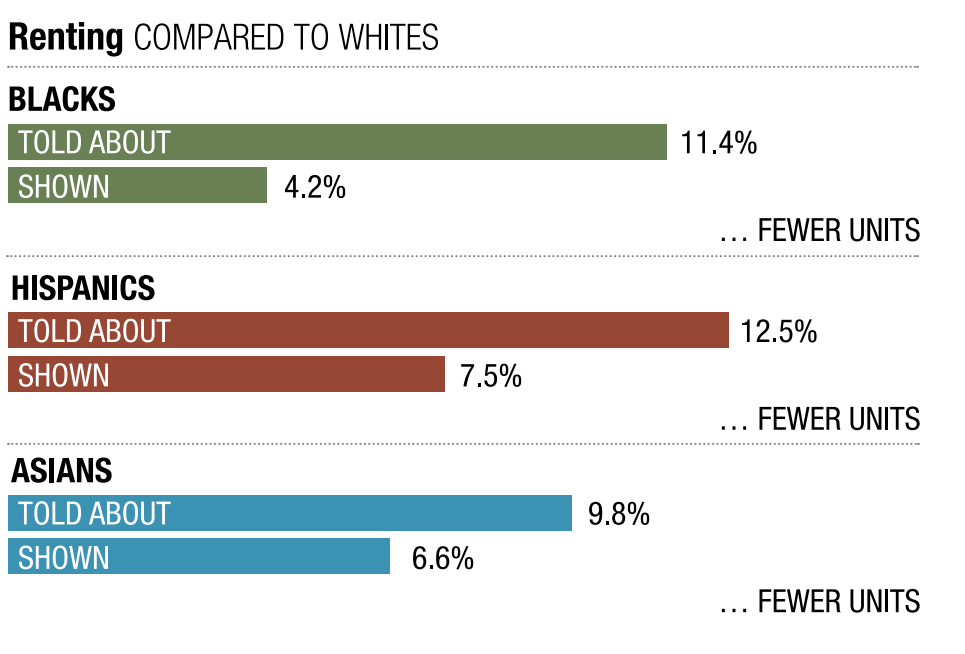

Structural forces perpetuate housing inequities. Landlords and real estate agents have contributed to racial/ethnic segregation by blocking minorities from moving to predominately white neighborhoods, which often leads to the exclusion of minorities from high-quality housing, schools, and other public services (Figure 5). Further, predominantly minority communities receive less investments by lenders to improve housing quality and neighborhood environment.

Increased awareness of the importance of adequate housing was a priority for the previous federal administration. The federal government was committed to launching initiatives that promote access to better housing for low-income families. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)’s 2014—2018 strategic plan aimed to increase access to safe and affordable housing, as well as promote housing self-sufficiency and home stability. The previous administration also enforced a number of measures that required cities to address racial disparities and housing segregation or face penalties. For example, the Affordable Housing program is one of the most comprehensive HUD programs to address the issue of housing affordability in the US. The program targets families who are cost-burdened and have difficulty affording necessities. In 2014, the government spent $18 billion on the Housing Choice Voucher program to help recipients to pay for housing, about $12 billion on project-based rental assistance to provide subsidized rent, and $7 billion on public housing. Children from low-income families that receive housing subsidies have better access to nutritious food, less developmental concerns, and maintain a healthy weight when compared to children from similar families on the housing support waiting list. Moreover, adults living in affordable housing are less likely to describe themselves as being in poor health than those living in unaffordable housing. Healthy Homes is another government-led initiative driven by the impact of housing on health outcomes. The initiative began in major cities like Boston, Cleveland, New York, and San Francisco after the emergence of asthma as a major health issue. The projects provide education and resources to household members to improve the safety and quality of home environments and identify housing deficiencies that affect health. Another initiative, Supportive Housing, provides affordable housing and community integration to individuals who experience homelessness and those placed inappropriately in institutional care. Several studies demonstrate that linking care management to supportive housing leads to improved health outcomes. A study evaluating supportive housing in Denver showed that 50 percent of residents experienced improved health status, while 43 percent showed better mental health outcomes and a 15 percent reduction in substance use. In 2009, then-President Obama signed the HEARTH Act, which consolidated supportive housing along with two other programs under the Continuum of Care program to help homeless people better their skills and income, in addition to providing stable housing and health care.

The change in the US political landscape brings uncertainties on the housing front. What lies ahead remains ambiguous. Criticism expressed by Ben Carson, the new HUD secretary, towards government policies that address racial segregation raises many questions about a potential shift in HUD policies to address housing inequalities, and creates an uncertain future about initiatives that link housing and health care. Moreover, President Trump has already expressed his skepticism of the benefits of policies that address housing inequalities. It shall fall to others, then—including public health—to maintain concerns about the housing conditions, segregation, and inequalities that we must work to keep central to the national agenda in this shifting political landscape.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A. Knox Professor, Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful for the contributions of Salma Abdalla, MD, MPH to this Dean’s Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: https://www.bu.edu/sph/tag/deans-note/

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.