Why Do We Do What We Do? Three Stories About the Role of Public Health.

Yesterday, the SPH class of 2017 received their degrees and took their first steps as alums. I have argued before that the work they will embark on is more important now than ever, that changes from demographic shifts like population aging and urbanization, and challenges like the opioid crisis and political uncertainty, call for a braver, more engaged public health. I would like, for today’s note, to share the stories of three figures who, in their own ways, illustrate the importance of our work, shedding light on the core principles of public health, and clarifying, I think, why we do what we do.

Yesterday, the SPH class of 2017 received their degrees and took their first steps as alums. I have argued before that the work they will embark on is more important now than ever, that changes from demographic shifts like population aging and urbanization, and challenges like the opioid crisis and political uncertainty, call for a braver, more engaged public health. I would like, for today’s note, to share the stories of three figures who, in their own ways, illustrate the importance of our work, shedding light on the core principles of public health, and clarifying, I think, why we do what we do.

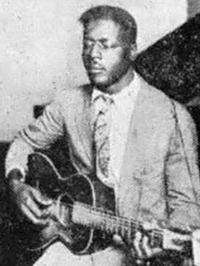

The first story begins with a spaceship. In 1977, the Voyager One spaceship lifted off into the unknown. On board was a gold-plated record, a collection of sounds meant to sum up the human species in case the craft ever encountered aliens. One song on the record is called “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground.” It was recorded in 1927, by the blues singer Blind Willie Johnson.

Blind Willie Johnson had a hard life. The story goes that, when he was a child, his father beat his stepmother for seeing another man, and she threw lye in Willie’s face out of spite, blinding him. He was always poor, playing and preaching on the streets to earn a living. In 1945, his house burned down. With nowhere to go, he lived in the ruins, sleeping on a damp bed until he caught malaria and died. His wife said that he had been refused treatment at a hospital, either because he was blind or because he was black. To some, Johnson’s story may seem like the tragedy of an individual. But we know that it is not. We know, for example, that while malaria may seem to have killed him, he actually died of poverty. We also know that the brutality of his upbringing was no outlier. Echoes of what he faced remain true today; black children in America are far likelier to witness domestic violence than white ones. Finally, we know that, while doctors may not be able to turn patients away on account of race anymore, pernicious gaps in treatment remain. Fundamentally, Johnson’s health was shaped by being born at a certain time, in a certain place, in a certain skin, under certain social and economic circumstances. Say he had received treatment for his malaria, the best money could buy. He still would have had to return to the same conditions of poverty that made him vulnerable to disease in the first place. It is public health’s job, then, to improve these conditions, toward the ultimate goal of improving the health of populations.

It is possible that such improvement could have saved the life of Salome Karwah, who died last February in Liberia. Karwah was a nurse, one of those who in 2014 dealt with the outbreak of Ebola in West Africa that killed more than 11,000 people. Before becoming a nurse, Karwah had her own personal experience with Ebola. Along with her family, she was among the first to become ill when the disease struck in 2014. Ebola claimed her father, mother, and uncle. But Karwah survived. During her time in a Doctors Without Borders treatment unit, the staff noticed her tendency to care for other patients despite her own condition. After she was discharged, she received an offer to serve as a counselor to the sick. For her work providing hope and comfort to the stricken, Karwah appeared on the cover of Time magazine as one of the “Ebola Fighters” collectively named Person of the Year in 2014.

Karwah lived through one of the most terrifying disease outbreaks in recent years, bravely helping many Liberians through her work. But that is not the end of the story. Karwah gave birth to her fourth child in February 2017, undergoing a C-section because of dangerously high blood pressure. Soon after returning home from the hospital, she collapsed. She then returned to the same hospital where she delivered her son, only to be refused treatment. According to Karwah’s husband, the doctor on duty would not touch her due to her status as an Ebola survivor. Several hours later, Karwah would eventually be admitted to the hospital after her husband begged Dr. Mosoka Fallah, a prominent Liberian epidemiologist who specializes in Ebola, to intervene on her behalf. But it was too late. She died two days later. While the exact physical cause of her death remains unclear, what is clear is that, like Blind Willie Johnson, her death was caused more by social conditions than by any disease. Karwah would likely not have died had she not delivered her child in Liberia—a country with the eighth highest maternal mortality rate in the world, where hospitals do not have the capacity to cope with complications due to childbirth. She would not have died if a terrifying disease, Ebola, had not been stigmatized. Her story could have been different.

If the stories of Blind Willie Johnson and Salome Karwah show us the power of structural forces to shape well-being, this next story affirms the power of individuals to make a difference, improving health in the face of injury, disease, and war.

Mary O’Connell, known as Sister Anthony, was born in 1814, and became a nun at the age of 21. She would go on to serve as head of nursing at Saint John’s Hospital in Cincinnati. Soon after the 1861 outbreak of the Civil War, she was asked by city leaders if a group of nuns could help soldiers at a Union Army camp where troops were suffering from a measles outbreak. Sister Anthony agreed, and this act of mercy would lead to even more service, as the nuns spent the war traveling with the army, caring for soldiers in hospitals and on battlefields. In a sense, Sister Anthony is still saving lives. She pioneered the technique of battlefield triage, allocating treatment among patients to maximize survival rates, a method used to this day. By treating Union and rebel soldiers alike, she married her innovation to the basic principle that health is a human right, no matter the circumstances.

But there is another reason why her story resonates in our time—Sister Anthony was an immigrant. She came to the US from Limerick, Ireland, at a time when Irish immigrants were met with the same hostility we now see leveled at immigrants from Latin America and the Middle East. I often wonder: How would our health be different had Sister Anthony not been admitted to the country because of draconian immigration laws? What is our role as public health professionals, then, in arguing for a fair, inclusive world that includes opportunities for many to make their mark, improving the conditions that make people healthy? It is important to remember that when we deny immigrants the chance to live in the US, we also deny our country the positive influence that they might have had on our lives and on our health. Building a society that is based on values of inclusivity is therefore key to safeguarding well-being.

Each of these stories illustrates the core values of public health. Just as doctors seek to mitigate the effects of disease to promote well-being, public health professionals seek to mitigate racial and gender inequities, homophobia, climate change, bad political decisions, and other structural factors that shape the health of populations. Public health works to create the cultural, economic, political, and social contexts that allow us all to live healthy lives. We are deeply proud that our graduates have chosen to commit themselves to this work, to building a world where Blind Willie Johnson and Salome Karwah would not have died, where immigrants like Sister Anthony need not fear hostility as they seek to invest their time and talents in a new life in a new country. We wish our alums well as they begin their journey, and we look forward to seeing how their stories unfold.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A. Knox Professor

Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Eric DelGizzo and Catherine Ettman for their contributions to this Dean’s Note, and to the congregation at the First Parish Unitarian Universalist Congregation in Brookline, a presentation to whom was the original motivation for this note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: https://www.bu.edu/sph/tag/deans-note/

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.