Our Neighborhoods, Our Health.

Frequent readers of these notes will know that I occasionally begin them with a brief acknowledgement of recent newsworthy events. I do this because it is often easy, especially now, for the sheer pace of the world to distract from important stories. No sooner have we begun to absorb one news item than it is eclipsed by many others. This makes it especially important, I think, to take time to focus on overlooked narratives—how they happened, and who they affect.

Frequent readers of these notes will know that I occasionally begin them with a brief acknowledgement of recent newsworthy events. I do this because it is often easy, especially now, for the sheer pace of the world to distract from important stories. No sooner have we begun to absorb one news item than it is eclipsed by many others. This makes it especially important, I think, to take time to focus on overlooked narratives—how they happened, and who they affect.

With this in mind, I wish to mention two stories that gripped me this week. The first is the continued humanitarian crisis in Puerto Rico. At this moment, the 3.5 million American citizens living on the island must contend with a shattered infrastructure, shortages of food and clean water, and a lack of electricity. This ongoing tragedy deserves far more attention than it has been given. At the same time, a terrorist bombing in Somalia—a country where I have done work—has claimed the lives of more than 300 people, and injured hundreds more. Yet this enormous attack has received barely a mention in our media space. Hopefully, bearing witness to these stories will help us recommit to building a world where such hardships are no longer deemed acceptable enough to be ignored. These events remind us of what matters most to the production of health—the conditions of peace, and the improvement of the social, economic, and environment structures that surround us.

Today’s note is, in part, an exploration of these foundational factors. I have written previously about the well-established link between physical environments and the health of their inhabitants, and how this influence operates on both a large and small scale. This week, I will focus on another aspect of our environment’s influence on our health—the role of neighborhoods in shaping well-being. Last Tuesday, our community was given a firsthand look at the power of this influence at our Diversity and Inclusion Seminar featuring Michael Patrick MacDonald, author of All Souls: A Family Story from Southie. I note that there is a significant body of literature on this topic, including some excellent books and reports. This note is intended, then, as both a very brief summary of the topic, and, with our new students in mind, an introduction.

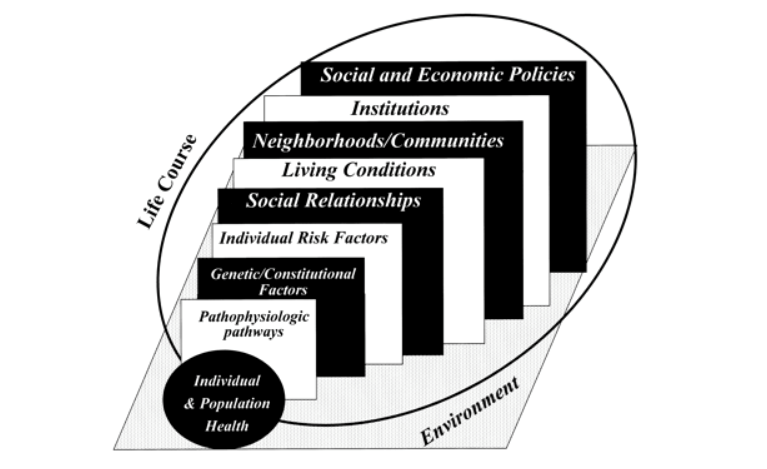

Neighborhoods are key to the multilevel, “upstream and downstream” determinants of health paradigm, which I have explored in a previous Dean’s Note (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Upstream and downstream determinants of population health

Kaplan G. What’s wrong with social epidemiology, and how can we make it better? Epidemiologic Reviews. 2004; 26(1): 124—135.

Broadly speaking, a focus on the link between neighborhood and health is part of the larger social determinants of health agenda that has become a growing priority for public health over the past few decades, in both research and practice. For example, Healthy People 2020 highlighted neighborhoods and built environments as key social determinants of health (Figure 2).

2020 Topics and Objectives, Healthy People 2020 Web site. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health Accessed October 10, 2017.

What features comprise a neighborhood? Neighborhoods are defined both in geographic terms—as physical spaces where people live in some degree of proximity—and in terms of the resources and characteristics shared by those who live in the same area, including their social connections, collective efficacy, income distribution, shared resources, public schools, and transportation.

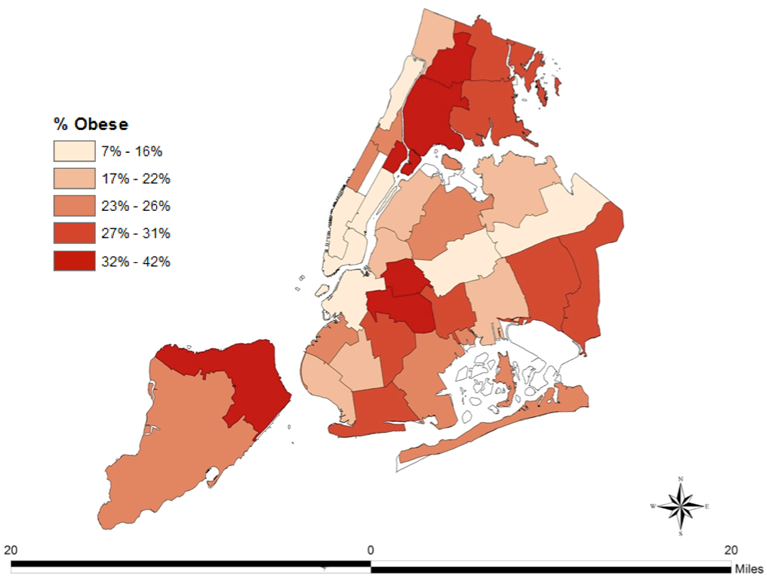

Inter-neighborhood differences in health are readily observable at even the crude level. By way of one illustration, Figure 3 shows differences in obesity prevalence by neighborhoods in New York City, demonstrating that obesity is substantially higher in neighborhoods clustered in parts of the Bronx, Staten Island, and Queens compared to other neighborhoods in the city.

Figure 3. Prevalence of obesity by neighborhood in New York City

Data from the Community Health Survey 2010, NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Web site. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/data/data-sets/community-health-survey.page Accessed October 10, 2017.

There are a number of key factors that work, both individually and collectively, to shape a neighborhood’s effect on health. These factors interact in complex ways; together, they shape the health of residents in the neighborhood. By way of illustration, three mechanisms are worth highlighting: the neighborhood’s built environment, its degree of economic advantage or disadvantage, and its level of overall social cohesion.

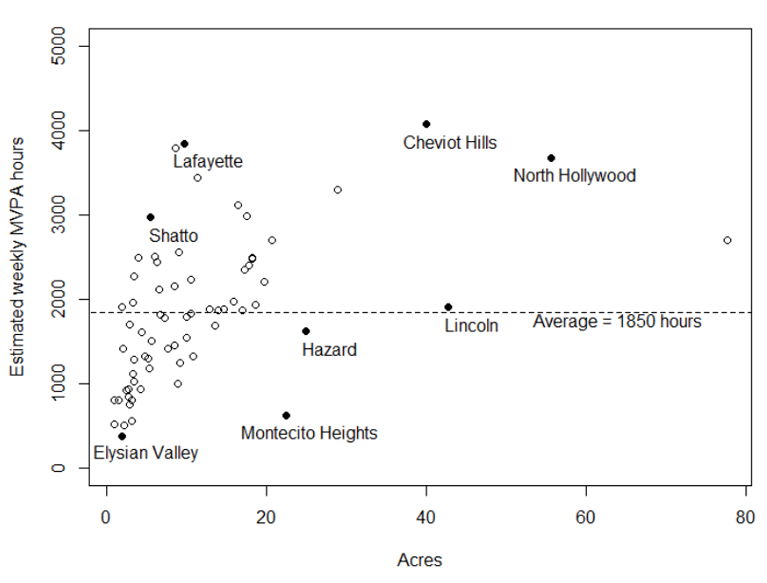

First, a neighborhood’s built environment affects health both positively and negatively. Neighborhoods that contain safe, accessible parks create space for residents to exercise, with all the attendant physical and mental health benefits of such activity. Figure 4 illustrates this, showing how the size of parks in Los Angeles neighborhoods is strongly associated with the average weekly hours of exercise among residents. Bike lanes, and the overall walkability of neighborhoods, can also promote well-being. However, when neighborhoods lack these features, or are located near major roadways or other pollution centers, the built environment can play a more harmful role, undermining health.

Cohen D, Derose KP, Han B, Williamson S, Marsh T, Raaen L. City of Los Angeles Neighborhood Parks: Research Findings and Policy Implications (2003—2015). Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2016.

Second, income and wealth disparities are powerful and pervasive factors in shaping neighborhood health. For example, Diez-Roux and colleagues found that living in economically deprived neighborhoods, as measured using US census data, was associated with a higher risk of coronary heart disease in various communities across the country, even when accounting for individual-level risk factors. Economic disadvantage, or the conditions of inequality itself, may directly influence mental health outcomes, by shaping exposure to adversity and stress. Neighborhood income can also influence well-being more indirectly, by determining where residents shop for groceries, whether they smoke, and their housing conditions, all of which are strongly linked with health outcomes. Income is also closely linked with education and employment, both of which matter for well-being. O’Campo and colleagues found that women living in urban neighborhoods with higher unemployment rates were more likely to report that they experienced domestic violence compared to women in the same city, with the same income level, but who lived in neighborhoods with lower unemployment rates. Among residents of São Paulo, Brazil, Silveira and colleagues found that lower education and income at the neighborhood level was associated with a higher risk of alcohol use disorders.

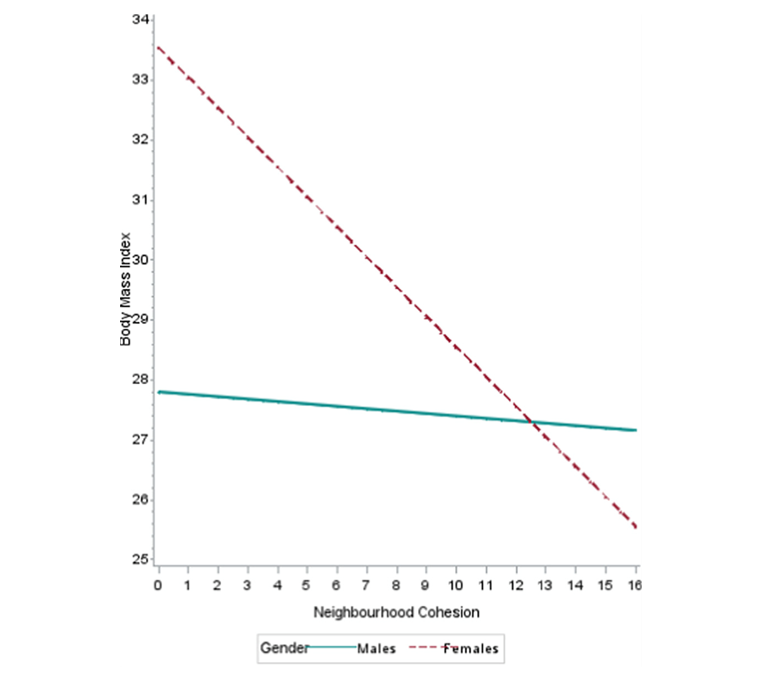

Third, neighborhood health may be shaped by the existence, or lack, of social cohesion. Social cohesion is “the willingness of members of a society to cooperate with each other in order to survive and prosper.” It is a neighborhood characteristic that can account for enhanced community resilience, or, when it is not present, greater uncertainty and hazard. One study in Shanghai, China, found that neighborhood satisfaction and social cohesion were strongly associated with health factors such as reported chronic conditions. Another study found a strong inverse association between neighborhood social cohesion and body mass index (BMI) among women living in Toronto, Canada (Figure 5). Neighborhood levels of social cohesion have even been shown to buffer post-traumatic stress symptoms following natural disasters.

O’Campo P, et al. The neighbourhood effects on health and well-being (NEHW) study. Health & Place. 2015; 31: 65—74.

Conversely, absence of social cohesion has been shown to be associated with worse health. Silver and colleagues found that social disadvantage, operationalized as an aggregate factor including unemployment levels and percentage of single-headed households, among other characteristics, was associated with depression and substance use disorder in the US.

One final note. Although the vast majority of science looking at the link between neighborhood and health has been observational, a few social experiments have indeed shown that changing neighborhoods and neighborhood characteristics improve health. Most notable is the Moving to Opportunity study, a housing experiment that relocated families from high-poverty neighborhoods to low-poverty ones. The experiment resulted in improved health outcomes for adult participants, including lower levels of extreme obesity and diabetes. This work, coupled with the body of observational work in the area, further reinforces the role of neighborhoods as drivers of population health and as a focus of public health effort.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A. Knox Professor

Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Laura Sampson, MS, and Eric DelGizzo for their contributions to this Dean’s Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: https://www.bu.edu/sph/tag/deans-note/

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.