Stepping Up: Reducing the Adverse Health Impacts and Inequalities of Climate Change.

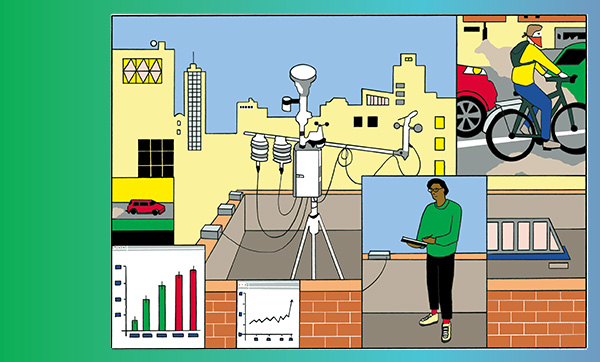

Illustration: Fien Jorissen, Heart Agency

Stepping Up: Reducing the Adverse Health Impacts and Inequalities of Climate Change

The science is irrefutable: climate change due to human activity poses an urgent threat to the environment and to the health of the public, with implications at the local, national, and global levels. But the science is also clear that the actions we take today can mitigate current and future consequences of extreme weather events that are increasing in frequency and intensity each year.

The School of Public Health is at the forefront of research that identifies and reduces the health impacts—and the social and economic inequalities— linked to climate change.

Representing the school’s climate, the planet, and health strategic direction, much of this work now takes place through SPH’s Center for Climate and Health (CCH), which launched on Earth Day 2022. This cross-disciplinary endeavor fosters cutting-edge research and training in this area, helping communities around the world to be healthier, more equitable, and more resilient to the effects of extreme weather events.

This is a public health issue that affects every one of us, and our actions today can help create communities that are more equitable and resilient in the future.

“Climate change is perhaps the greatest threat to our health and well-being, and the concentration of people working in this space at BU School of Public Health is unparalleled to any other institution,” says Gregory Wellenius, CCH director and professor of environmental health (EH) and the strategic direction lead for climate, the planet, and health. “This is a public health issue that affects every one of us, and our actions today can help create communities that are more equitable and resilient in the future.”

Focusing our energy

As the year 2022 was predicted to be among the top 10 hottest years on record, many SPH faculty are studying the physical, mental, economic, and social impacts of extreme heat. Wellenius and Amruta Nori-Sarma, assistant professor of environmental health, published studies this year that linked hotter-than-normal days to increased visits to the emergency department nationwide among adults experiencing mental health crises, and among children and younger to middleaged adults experiencing heatrelated illnesses.

Climate and health research at SPH spans three broad pillars: understanding the adverse health impacts of climate change; quantifying the immediate health benefits of actions to limit climate change in the future (i.e., “climate co-benefits”); and climate change resilience— evidence-based research and guidance that enables cities to prepare for and adapt to this worsening crisis.

“We found consistent rates of emergency department visits for mood, stress, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, and self-harm, indicating that extreme heat is an external stressor that can exacerbate existing adverse health issues,” Nori-Sarma says. “It’s important that we identify the populations most vulnerable to these conditions and tailor interventions and messaging to meet the specific health needs of communities.”

Madeleine Scammell and Patricia Fabian, associate professors of environmental health, are doing just that as co-principal investigators of C-HEAT, an ongoing project with environmental justice organization GreenRoots that examines heat exposure in Chelsea and East Boston households to inform policies that facilitate cooling in vulnerable homes. In Chelsea, the researchers measured a seven-degree difference between the hotter and cooler blocks on the hottest days.

“Through our mapping, we identified local heat islands and overlaid these with areas with a high density of vulnerable populations, such as affordable housing blocks, and shared this data with local stakeholders to determine where the cities can invest in cooling interventions,” says Fabian.

These efforts led to the installation of white roofs, trees, and water fountains.

According to Scammell, air conditioning is the most important cooling factor indoors, but many residents lack physical or financial access to cooling systems.

Ultimately, “there is no policy to protect people from heat at work or at home,” she says. “Building resilient communities will happen through relationships, and through people becoming empowered and organizing to change policies and systems that are beneficial to their neighborhoods.”

The heat is on to do more

Keith Spangler, research scientist in environmental health and the Biostatistics and Epidemiology Data Analytics Center, and faculty are studying how to improve climate exposure measurements that inform local heat alerts. Cities use varying criteria that may identify extremely hot days, but not necessarily the days that are most dangerous for health.

Cross-collaboration is crucial to the school’s climate and health work. Marcia Pescador Jimenez, assistant professor of epidemiology, studies links between greenspace exposure, neurodegenerative diseases, and racial disparities in health, while Jonathan Jay, assistant professor of community health sciences, has analyzed data that suggests a sizable proportion of shootings in the US are attributable to above-average daily temperatures.

“Some of the same interventions can address both heat and gun violence,” Jay says. “Tree canopy can offset the urban heat island effect, and it also appears that neighborhoods with more tree cover have lower gun violence.”

Faculty are also applying their climate and health expertise to international projects on air pollution. Kevin Lane is an assistant professor of environmental health and the SPH lead for an international project called the Consortium for Health Effects of Air Pollution Research (CHAIR India), a multi-university collaboration of researchers who created a nationwide modeling tool this year that builds daily gridded models with air pollution and heat metrics across India spanning the past decade.

“These models enable researchers to conduct long-term climate studies at fine spatial resolutions to better understand the causal impacts of mortality due to air pollution and extreme temperatures,” Lane says.

Clearing the air

Patrick Kinney, Beverly A. Brown Professor of Urban Health in the Department of Environmental Health, has also developed local and international data and solutions to the health consequences of air pollution.

Twenty years ago, his research was among the earliest studies showing that climate change worsens air pollution and poses health risks. In more recent work, Kinney analyzed the potential air and health benefits of Boston’s plan to achieve zero carbon emissions by 2050, and he has collaborated with faculty researching how greenspace expansion and bike and pedestrian infrastructure can bring both health and climate benefits.

“By reducing carbon emissions, we have an opportunity to reduce other air pollution emissions,” he says. “By implementing low-carbon transportation options, we can clean up the air in cities at the same time that we’re helping the planet— a win-win situation.”