The Cost of Pharmaceuticals, the Role of Public Health.

A brief detour, before I begin today’s note. Recent data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests that death rates are rising for the first time in over a decade in the US. These data come despite extraordinary levels of spending on medical care in this country, and reflect very much the observation I have made here repeatedly that the core drivers of population heath are the social, cultural, and economic conditions that produce health. Unfortunately, our over-focus on the curative, giving us perhaps some of the best medical care in the world, do little to prevent disease and to promote healthy populations. It is the place of public health to relentlessly communicate this message, and to move us towards a world where we, and other populations globally, live longer, healthier lives, needing far less recourse to treatment and medical care.

On to today’s note.

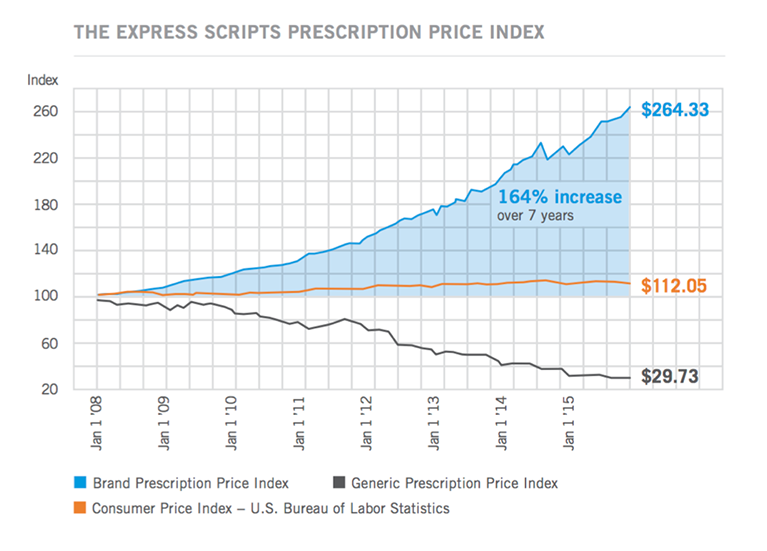

A small miracle took place during the tumultuous early months of the 2016 presidential race. In that season of insults, feuds, and partisan rancor, Hillary Clinton, Marco Rubio, and Donald Trump all found something to agree on. The issue was drug pricing, and the increasingly high cost of prescription medications. Trump said that he thinks Medicare should negotiate price discounts, Rubio accused drug companies of profiteering, and Clinton unveiled an “aggressive plan” to save more than $100 billion on pharmaceutical costs over 10 years. The reason why this matter is so urgent, and so politically potent, is perhaps best expressed by a new report from the US pharmacy benefit management organization, Express Scripts. The report found that the average price for common, brand-name prescription drugs has increased 164 percent since 2008 (see Figure 1), even as the price of generic drugs has declined.

“The Express Scripts Prescription Price Index.” Image from The Express Scripts 2015 Drug Trend Report. The Express Scripts Lab. March 2016.

These kind of data, along with the widely reported actions of former Turing Pharmaceuticals CEO Martin Shkreli—who has been criticized for his company’s decision to raise the price of the antiparasitic drug Pyrimethamine (Daraprim) by more than 5,000 percent—have kept the issue of drug pricing in the news and at the forefront of public debate.

Here in Massachusetts, we have seen this debate play out in a number of high-profile ways. In January, state Attorney General Maura Healey wrote a letter to Gilead Sciences CEO John Martin, requesting that the company consider lowering the price of Sovaldi, a drug capable of curing Hepatitis C. Healey warned that Solvaldi’s $1,000 price tag may constitute an unfair trade practice under state law. Boston-based Vertex Pharmaceuticals has also come under fire for the $259,000 annual cost of its cystic fibrosis drug, Orkambi. The company has said that the price of Orkambi reflects the astronomical overhead involved in developing such a drug over a period of many years. Continuing this work, they claim, will require “a very significant investment.”

This claim is not unreasonable. It can take over a decade for a medication to reach the point when it is ready to be licensed for human consumption, and the expense involved can be considerable. A controversial 2014 study conducted by the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development suggested that the average cost to bring a drug to market had ballooned to $2.6 billion; the study has been challenged given its having been funded, in large part, by the pharmaceutical industry and its failure to identify which medicines were used to make the estimates.

The story, however, is not so straightforward—there is also the matter of federal funding for drug research and development. Often the costs for such innovation are subsidized by the taxpayer. The National Institutes of Health, for example, spend close to $32.3 billion annually on medical research. This lets drug companies offload much of the risk involved in early stage pharmaceutical research and development, freeing them to spend the majority of their budgets on marketing.

Be that as it may, the cost of drug development—in both money and time—remains high.

Why else are we seeing this spike in drug costs? One additional reason could be the current high number of mergers in the pharmaceutical industry. Mergers can lessen competition, driving innovation down and prices up. These mergers have been decried by everybody from those who claim they lead to “bad science” (due to cuts in research and development spending), to those who suggest that they are often little more than cynical attempts to get a better corporate tax rate.

Another reason for companies charging so much for drugs in the US is that, quite simply, there are no regulatory efforts to stop them. The US is, in this respect, rather unique. In all Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries except the US, price controls for drugs are commonplace. In Switzerland, drugs are only approved if they are proven to be both medically successful and cost-effective. Australia’s Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme provides government-subsidized drugs, and lists the medications, and their fixed prices, online. Canada has a drug review board that studies the effectiveness of a given drug, and makes recommendations to public drug plans about reimbursement. Not only does the US not take any of these steps, but, in 2003, our Congress refused to even allow Medicare to negotiate prices with drug companies.

Given the expense involved in producing drugs, it does not seem out of line that drug companies should expect to make a fair profit. The operative word here, however, is “fair.” While a growing chorus of opinion suggests that the profits of these companies are anything but, there is also a body of opinion defending current pricing. As Professor Leonard Glantz has written, the current political climate makes it unlikely that we will see the problem of pricing solved legislatively, through regulation at the federal level, any time soon. The questions facing us here are perhaps narrower. What are the consequences of high drug pricing? And, do they present an opportunity for public health to play a role in this debate?

At core, the high cost of treatment has created a real market demand for just the kind of prevention agenda that should be at the heart of public health. Circling back to Sovaldi, we see a case in point. Sovaldi stands to make a tremendous difference in the lives of those affected by Hepatitis C, and it would be a shame if the drug’s cost prevented these people from receiving care. While it is important to note that Gilead has licensed the drug to generic manufacturers to be sold for about $150 per year, how much better off would patients be if, in their case, the argument over Sovaldi’s pricing was rendered moot because they did not have Hepatitis C to begin with? What if the disease, in fact, no longer existed?

We know that the effects of disease can be mitigated through prevention. Historically, needle exchanges and education campaigns have been effective in preventing Hepatitis C without recourse to years of expensive drugs or paying $1,000 per pill. Had these interventions taken hold sooner, it is possible that the wave of people with Hepatitis C, now in need of Sovaldi, would be much smaller than it is today.

Hidden in the political rancor around drug pricing is an implicit acceptance of our fundamental reliance on drugs and medical curative strategies as the cornerstone to our approach to health. A well-articulated prevention agenda, therefore, is positioned to make real gains. Prevention represents a “third way” between the extremes of paying high costs or going without needed care. For populations to reap the benefits of this approach, we need, first and foremost, to do a better job conveying the importance of prevention, and its foundational principles. Prevention is not simply cancer screening, or environmental regulation, or even working to improve health by reducing poverty. It is all of these measures and more—the sum of its parts. To truly improve population health, a strategy of prevention must be carefully calibrated to target the specific social, political, economic, and environmental causes of disease. For this to happen, we must make it clear, in our scholarship and in our broader translation of our public health agenda, that when we talk about prevention, we are talking about a comprehensive approach to tackling the fundamental drivers of poor health. This is not to say we advocate prevention at the expense of treatment; far from it. We recognize that treatment is a vital component of a broader prevention strategy, and we must take care that our intentions in this respect are not misunderstood. But when resources are so disproportionately allocated in the direction of expensive treatment, it behooves us to risk sounding a little one-note from time to time in our appeals. Amidst the clamor of this debate, we must make sure that the voice of public health is heard.

I recognize that the challenges around drug pricing touch a nerve, and that in some respects a cry for lower drug prices is an easy reflection of a contemporary hot-button issue. However, it is also true that the pharmaceutical industry presents extraordinary opportunities for curative care, particularly as novel developments create ever more dynamic opportunities to target disease. Harvard Medical School Dean Jeffrey Flier has argued, and I agree, that we must strike a balance between holding drug companies accountable and imposing strictures upon innovation.

As I have written in other Dean’s Notes, the goals of public health are substantially different than those of medicine, and the challenges posed by high drug prices suggest here the importance of a public health preventive approach, both towards improving health, allowing healthier, better lives, and towards minimizing the need for reliance on medications—obviating some of the current challenges we collectively face in dealing with high drug prices.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A. Knox Professor

Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Professors Richard Laing and Christopher Gill, and to Eric DelGizzo, for their contributions to this Dean’s Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: https://www.bu.edu/sph/tag/deans-note/