Learning from Measles.

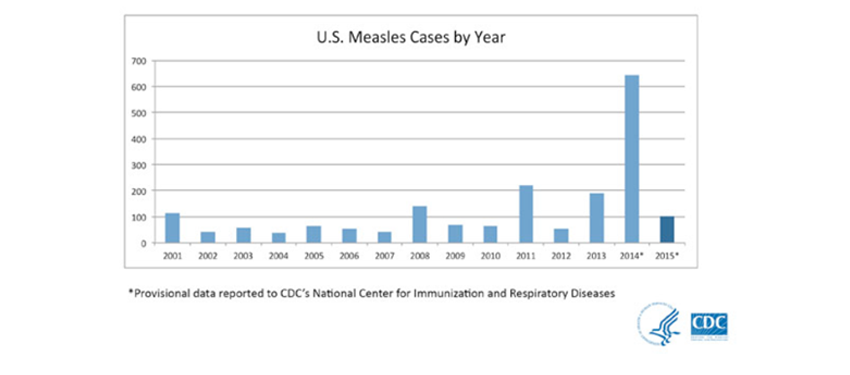

By the end of January, one month into 2015, the number of cases reported in the United States, 102, exceeded the yearly totals for 9 of the last 14 years [see figure 1, below]. These cases were reported in 14 states, with most arising as a result of an outbreak at Disneyland/Disney California Adventure Park in late December 2014. Secondary cases were also reported as part of this ongoing outbreak, and the California Department of Public Health noted that infectious cases visited Disney theme parks in January 2015. Most of those who contracted measles in this outbreak were reportedly unvaccinated. Measles was declared eliminated in the United States in 2000; given that measles is endemic throughout the world, travelers may bring the disease into the United States and transmit it among pockets of communities that are unvaccinated or under-vaccinated. The initial source of the current outbreak is unclear, but as of January 29, 2015, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that links to travel history in Dubai, India, and Indonesia were being investigated. Indeed, in 2014 there was an enormous uptick in the incidence of cases, with the largest outbreak (383 cases) occurring among unvaccinated Amish communities in Ohio. Overall, in 2014, 644 cases of measles were reported, approximately seven times the mean number reported between 2001 and 2013 (89 cases) and about three times as many as reported in 2011 (220 cases), which had the next highest number of annual cases in that period. Many of the 2014 cases were thought to be associated with a large outbreak in the Philippines.

Sorting Through the Noise

The recent outbreak traced to Disneyland parks in California has sparked a deluge of news media stories on measles, vaccines, and the now roundly discredited links between the MMR vaccine and autism. Internet interest in the issue has dramatically increased compared to previous years. As the Super Bowl approached, public health officials in Arizona were wary of a potential outbreak. Arizona’s Department of Health Services’ Director Will Humble was quoted as saying, “This is a critical point in this outbreak. If the public health system and medical community are able to identify every single susceptible case and get them into isolation, we have a chance of stopping this outbreak here.” USA Today published an editorial on January 28 titled “Jail ‘anti-vax’ parents,” and the satirical website The Onion published a piece titled “I Don’t Vaccinate My Child Because It’s My Right To Decide What Eliminated Diseases Come Roaring Back.” As covered by ABC News, infectious disease experts are suggesting that “for measles to become permanent—that is, become ‘endemic’—again to the U.S., measles immunizations would have to drop below 90 percent.” Hovering close to that threshold, the rate of measles immunization in the United States in 2013 was estimated to be 91% by the World Health Organization.

Perhaps as full testament to the heat around this issue, a number of potential presidential candidates have also weighed in on vaccinations, and it has now become a campaign issue, with some conservative hopefuls supporting the right of parents to choose whether to vaccinate or not as a matter of personal choice or liberty. In contrast, pediatricians, including some who have previously supported the right of parents to choose whether to vaccinate their children, are being pressured by parents who do vaccinate their children to refuse to see children whose parents will not. Finally, it is worth noting that low-income countries such as Tanzania have higher vaccination rates than the United States, focusing attention on this intuitively unexpected, even absurd, contrast between wealth and vaccination coverage.

In some ways the rise in not vaccinating children is puzzling, given the amply demonstrated health benefits of vaccination. As Kim Shea, assistant professor of epidemiology, wrote in a recent opinion piece for BU Today, “Nothing about vaccination is controversial.” To this point though, an interview with Dan Olmstead, editor of the website Age of Autism, “the Daily Web Newspaper of the Autism Epidemic,” is illuminating. The site is, in its own words, “published to give voice to those who believe autism is an environmentally induced illness,” but much of the website content is dedicated to raising awareness about the purported and roundly discredited link between the MMR vaccine and autism. The belief that the MMR vaccine causes autism stems from a now retracted 1999 article in The Lancet by Andrew Wakefield, and persists despite a formal retraction grounded in evidence of academic dishonesty, financial conflicts of interest, and non-replicability. The most recent fuel to the anti-vaccine fire was the August public release of recorded conversations with a CDC researcher named William Thompson, in which he says that a 2004 article published by CDC authors withheld the finding of a positive association between MMR vaccine timing and autism in a subgroup of African American boys. The recordings were released by Brian S. Hooker, who also published a re-analysis of the data used in the 2004 CDC study, which reported that very subgroup finding that Thompson says was suppressed. The August article by Hooker has since been retracted by the editors due to “undeclared competing interests” and “concerns about the validity of the methods and statistical analysis.” Most importantly, the belief that the MMR vaccine causes autism persists despite an ever-growing mountain of evidence to the contrary. Perhaps it falls into the category of what Paul Krugman calls “zombie ideas”—“policy ideas that keep being killed by evidence, but nonetheless shamble relentlessly forward, essentially because they suit a political agenda.” Interestingly, findings from a recent study suggest that current public health communication strategies aimed at decreasing vaccine misperceptions and increasing intent to vaccinate may not only be ineffective, but also counterproductive.

Learning from Measles

Which brings those of us in public health to an odd impasse. What do we learn from this ongoing measles outbreak and the seeming intransigence of unfounded beliefs that fuel behaviors that are amply documented to adversely affect health? Three core observations emerge that suggests lessons that can be learned from the current outbreak.

First, general public understanding of health is limited, and often ill-informed. This creates an opportunity for false ideas to take hold, particularly if they are grounded in seemingly compelling notions (i.e. vaccines may precede autism), or if emerging from apparently credentialed experts (e.g., CDC scientists). This points to fundamentally limited literacy about health in the US population. While early universal education in primary and secondary schools has, in recent years, embraced education about individual health, there is no comparable effort to bring about popular education about public health, leaving much of the production of health in populations a mystery for most of the population.

Second, while the growing democratization of digital information has made enormous amounts of information available to many, much of this information is chaotic and not particularly informative, beyond the ready sound bite or compelling data point that may, or may not, contribute to a better understanding of complex issues.

Third, insofar as the two observations here are indeed right, academic public health has a central role to play both in educating the public about the health of the public, and in ensuring that we contribute equally to the broader health conversation, as do many others with far more impeachable credentials. It has long been canonical in schools of medicine that it is one of the roles of the physician to educate the patient about her health. Public health is concerned with the health of populations, and the education therefore of the public is our concern, and our responsibility. Clearly many far less qualified individuals are ready to rush in to fill the void in our stead. The task is not easy, but it must stand at the heart of a translational agenda for a premier academic school of public health.

It is to this end that we have discussed how translation shall, as we look forward, serve as a third pillar to our activities (together with knowledge generation and transmission to our students). The current measles outbreaks points both to the challenges inherent in doing this well, but also to the risks if we, and our colleagues in the public health community, fail to embrace this charge.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Professor, Boston University School of Public Health

@sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I would like to acknowledge the help of Gregory Cohen, MSW on this Dean’s Note.