Pasteur’s Quadrant and Population Health.

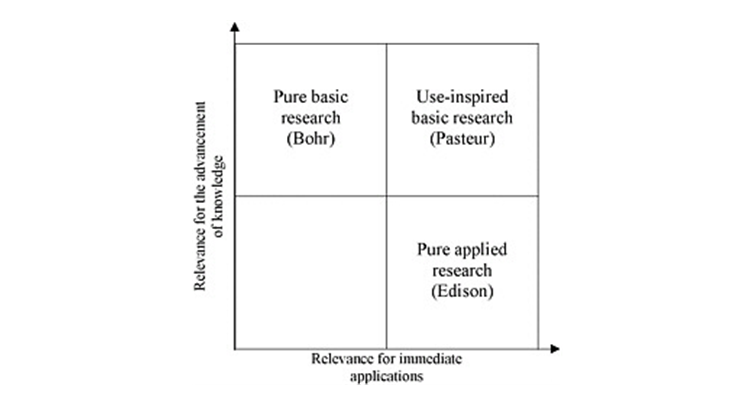

In 1997, Donald Stokes published his book Pasteur’s Quadrant: Basic Science and Technological Innovation. In the book, Stokes tried to find a way to reconcile the goals of science with the imperatives under which government operates, aiming to forge a new compact between science and government. His elegant, and much cited, synthesis for this centered around Pasteur’s quadrant, shown in the figure below.

In 1997, Donald Stokes published his book Pasteur’s Quadrant: Basic Science and Technological Innovation. In the book, Stokes tried to find a way to reconcile the goals of science with the imperatives under which government operates, aiming to forge a new compact between science and government. His elegant, and much cited, synthesis for this centered around Pasteur’s quadrant, shown in the figure below.

Stokes DE. Pasteur’s Quadrant. Basic science and technological innovation. Brookings Institute 1997.

Stokes anchored the potential contributions of science to a two-by-two grid and used scientists he deemed paradigmatic to illustrate his general points. Therefore, Louis Pasteur, whose work was at the core of advancing our understanding of infectious disease but was also directly applicable to the evolution of vaccination, resides in “Pasteur’s quadrant” at the intersection of advancing basic science knowledge and knowledge that is use-inspired, or “useful.” Nils Bohr, the Danish physicist whose work helped advance our understanding of quantum theory and atomic structure, resides in the top left corner, where work aspires to advance knowledge with little attention to its immediate application. Thomas Edison, meantime, the American inventor whose contributions include the practical electric light bulb, occupies the bottom right quadrant, where work with immediate relevance dwells, applying knowledge to practical use that aims to improve the world.

Stokes’ paradigm was itself an update of an earlier, more linear conception of the link between scientific knowledge and its applications proposed by Vannevar Bush in his report Science, The Endless Frontier, published some 50 years earlier. Although over the past two decades, several scholars have suggested updates to Stokes’ schema, his paradigm remains helpful and a useful guide for science to grapple with a perennial tension between its goals—advancing knowledge and providing ideas that can help propel the world forward.

I have long thought that this paradigm has particular utility for structured academic thought. But of particular interest to us is this: how does thinking about this paradigm help us understand the production of knowledge, and its potential utility, in public health?

In many ways, our work embodies the very tensions that Stokes was trying to reconcile in writing his book. We often say that we are concerned with producing knowledge so that we may improve the health of populations. The definition of epidemiology—the quantitative heart of population health science—typically involves understanding the causes of health and disease so that we may intervene. Our work in health policy tends to be linked directly to analysis of policy prescriptions and options that explicitly aim to improve population health. And environmental health sciences are deeply concerned with the impact of pollutants on human development, with the goal of reducing the burden of these pollutants in the environment. Therefore, to some extent, population health scholarship embodies the work in Pasteur’s quadrant. We aim to advance knowledge while having that knowledge be applicable to the production of population health. I have also wondered, however, whether this paradigm elides some subtleties in how we do our work, and whether we do not, through an over-focus on Pasteur’s quadrant, miss opportunities to advance both knowledge and its usefulness.

First, it seems almost paradigmatic that the work of professional schools involves an engagement with work that has utility—that is, with the production of useful knowledge. Part of our charge emerges directly from that role, and from our role in preparing future professionals engaged in the aspirations of public health. I will comment on the role of professional schools as I see them in a future Dean’s Note. It seems worth appreciating, however, the challenges we face in articulating what may be useful knowledge, to whom, and when. I have written papers in the past urging epidemiology, my own area within public health scholarship, to engage scholarship of consequence. I intended to provoke a discussion about how we may best, in public health, ask questions that are relevant to the health of populations, leading me to grappling with questions about what might matter most in public health. This, however, suggests that we need to be clear-eyed about whether our work indeed has potential utility, and to weigh decisions about the work we engage in against some yardstick that determines relative utility of work as mapped onto the challenges faced by public health. At face value, this is straightforward—e.g. a lot of people die from heart disease and we should do something about it. But in many other ways it is extraordinarily complicated—e.g. should work that aims to improve individual behavioral approaches to dietary choices, tailored to genetic risk, be prioritized when evidence suggests relatively limited effectiveness of such efforts? Therefore, an engagement with Pasteur’s quadrant must involve critical self-reflection about the work that we do and whether it is indeed likely to have salience. Underlying some of this are inevitably the values that animate us. For example, if we prioritize health equity, we are much more likely to prioritize scholarship that aspires to improve health among disadvantaged populations, even if that comes at the expense of slowing down overall achievement in population health gains.

Second, placing ourselves in Pasteur’s quadrant as we do, our work is, in some ways, a bold expression of confidence in the direct utility of what we do at the time we are doing it. We recognize Pasteur’s work as useful insofar as it laid the foundations of much of our understanding of vaccinology. His work, when it was being done, was far less clearly useful or linked to the health of populations. The path of discovery is windy and not infrequently tortuous, and it is perhaps a hubristic step too far to say that we know what line of inquiry will definitely lead to utility and relevance to the work of population health improvement. However, the causes of population health change over time, and embarking on work that one knows will be useful going forward is a tall order.

Third, the identification of approaches to the improvement of population health arises, for example, from fields that are far removed from our typical public health scholarship—fields such as economics or sociology that aim to understand how the world works with nary a thought to health. It is the synthesis of disciplinary work that is forged after the production of the original knowledge that then lends applicability to public health. The nature of public health as a truly interdisciplinary and even trans-disciplinary field suggests that innovation in public health will inevitably come from discovery in other disciplines put to use through adoption to public health questions. This is a far messier, but perhaps far more realistic, picture of how knowledge that can lend itself to the production of public health is generated. This puts our work somewhere at the intersection of the Pasteur and Bohr sides of the Stokes schema, although the utility of engineering approaches to the work of public health is not lost either, suggesting that a dash of Edison is also useful in the mix. Additionally, anyone who has been involved in the process of generating knowledge recognizes the role that serendipity plays in discovery science, and, commensurately, the role that serendipity plays in the production of health within complex human systems. This suggests that our capacity to anticipate the significance of what we might do is substantially more tenuous than a linear path would have us think.

In summary, the initial appeal of Stokes’ paradigm is somewhat complicated when one dives deeper into the real mechanics of the generation of knowledge in public health, and the utility of that same knowledge towards improving the health of the public. I have come to think that rather than dwelling in Pasteur’s quadrant only, our work rightly crosses into Bohr and Edison territory, and that we would do well to accept and nurture such cross-quadrant incursion. That may be less clarifying than a scientific taxonomist might like, but perhaps speaks to the intellectual breadth of the academic public health enterprise.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Professor, Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: https://www.bu.edu/sph/category/news/deans-notes/