Families and the Effects of Mass Incarceration.

Today’s Dean’s Note was originally meant to run last weekend, on Father’s Day, but was preempted by our comment on the horror in Orlando. We therefore turn from the problem of gun violence and hate to another harmful element in American society: mass incarceration.

Today’s Dean’s Note was originally meant to run last weekend, on Father’s Day, but was preempted by our comment on the horror in Orlando. We therefore turn from the problem of gun violence and hate to another harmful element in American society: mass incarceration.

Father’s Day represents a natural touchpoint to reflect on the influence a parent has on the life of a child. Parents can help determine everything from a child’s eating habits, to their sleep patterns, to their familiarity with the types of basic, health-centered best practices that, once mastered, safeguard well-being throughout life. Given the central role a parent plays in helping a young person develop into a functioning and healthy adult, it makes sense that the lack of a parent would have a similarly profound effect. With this in mind, I would like to focus on what has been an especially destructive force in American family life, forcing many parents to raise children without the support of a spouse: our country’s tragic history of mass incarceration.

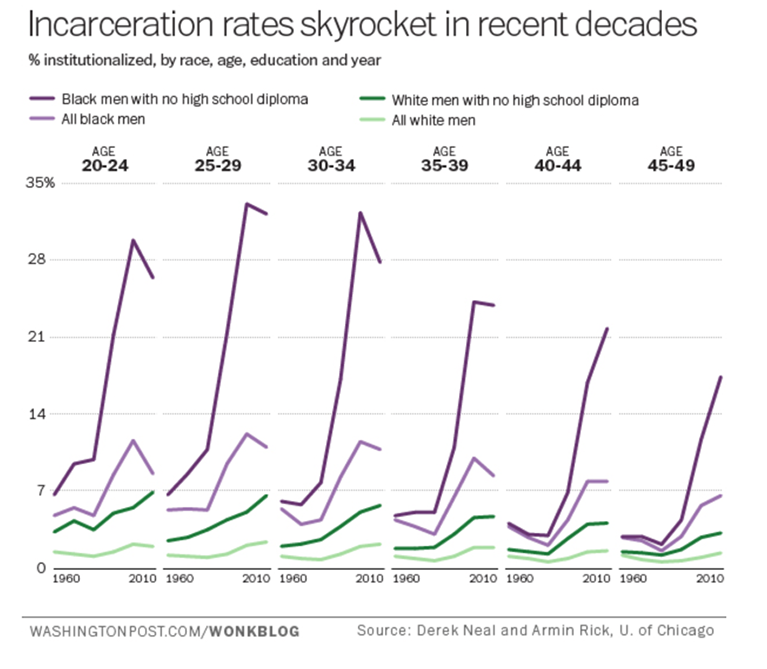

I have written previously about incarceration; however, I find its influence on families runs deep enough to warrant special consideration. A caveat, then, before I begin. There is a danger of oversimplifying the issue of mass incarceration and its effect on families. We cannot assume that a child would always be better off if her incarcerated parent returned to play a part in her life, nor can we assume that the children of single parents are invariably at a disadvantage, although data suggest that they often are. Nevertheless, the number of incarcerated people in the United States is so high—driven in no small part by men incarcerated for many years, often for nonviolent drug offenses—that it is a short and easy step towards recognizing that mass incarceration in this country is a true epidemic, and its effects are pervasive. Perhaps the two most striking qualities of mass incarceration are the rate at which it has accelerated in recent decades and the degree to which it disproportionately affects black men (Figure 1).

Pew Research Center. Chart of the Week: The black-white gap in incarceration rates. 2016 Source: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/07/18/chart-of-the-week-the-black-white-gap-in-incarceration-rates/.

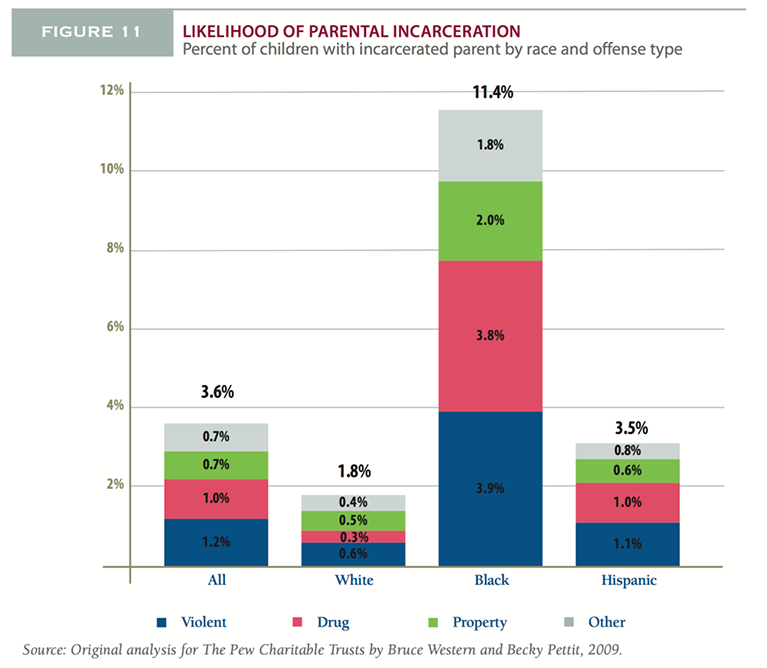

An estimated 2.7 million American children have an incarcerated parent. The problem has become so common that Sesame Street recently introduced a character with an incarcerated parent, to teach children how to cope with this difficult situation and the shame that can accompany it. Even worse, the data suggest an extraordinary racial disparity: 11.4 percent of black children have an incarcerated parent, 3.5 percent of Hispanic children, and 1.8 percent of white children. Non-violent offenses comprise two-thirds of the convictions reflected by these incarceration rates, with about one-quarter coming from drug offenses (Figure 2).

The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2010. Collateral Costs: Incarceration’s Effect on Economic Mobility. Washington, DC: The Pew Charitable Trusts.

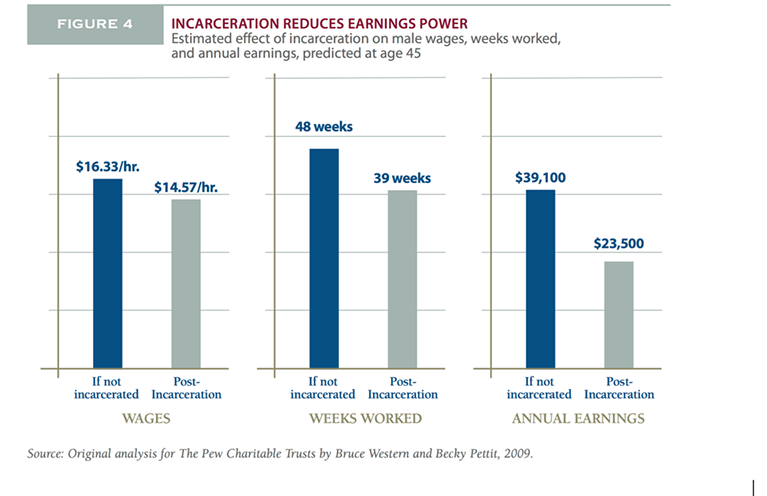

What are the effects of incarceration on families? Pew Research Center data indicate that more than two-thirds of incarcerated men had been employed prior to serving their sentence, and that nearly half had lived with their children before going to prison. Additionally, more than half of imprisoned parents were the principal earners supporting their children. When a wage-earning parent is suddenly removed from the scene, the burden falls on the remaining parent to provide for the children, pressuring families economically. This can continue even after the absent parent has been released from confinement—incarceration reduces earning power, compounding the financial challenges affected families can face (Figure 3).

The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2010. Collateral Costs: Incarceration’s Effect on Economic Mobility. Washington, DC: The Pew Charitable Trusts.

Beyond the immediate effects of incarceration on the families of those serving sentences, and the imprisoned individuals themselves, there can also be negative consequences for entire communities. A 2015 study found that those living in neighborhoods with high incarceration rates are more likely to meet the criteria for a major depressive disorder or a generalized anxiety disorder than individuals living in neighborhoods with lower incarceration rates. When we view incarceration as a purely individual risk factor, primarily the concern of the incarcerated and their immediate families, we miss an equally important and larger picture. In places with high incarceration rates, incarceration has become part of the very ecology of communities, shaping health in a way more akin to other environmental determinants than a random hardship affecting only a select, unlucky few.

While the complexity of this problem may be daunting, its very scope means that there are many areas where we in public health can make a difference. An ideal solution would be, of course, to bring an end to the “prison-industrial complex” that has so fundamentally affected the lives of so many. However, in the short-term, apart from our research and scholarship, there are two key areas where public health can help. First, we can improve matters through clear policy and translational work. Central to the question of policy is the practice of assigning mandatory minimum sentences to non-violent drug offenders. When the punishment is so disproportionate to the crime, it does nothing to help society or promote rehabilitation—it is, in fact, a distortion of justice. It falls well within the responsibility of public health to be clear and present in pushing against policies that exacerbate social forces that damage the health of populations—like mass incarceration. This means robust communication efforts, and engaging with the media to inform the public of incarceration’s deleterious effect on the well-being of communities at large. We must also be clever about how we help tell the stories of incarceration and its consequences, generating empathy and nudging a status quo that has long been unacceptable.

Second, we have a responsibility to collaborate with partners within the public health community whose work tackles the downstream consequences of mass incarceration. When prisoners are released, programs and resources that allow successful reengagement with society are critical. As Kansas Governor Sam Brownback once said, “Everybody—the ex-offender, the ex-offender’s family and society at large—benefits from programs that equip prisoners with the proper tools to successfully reintegrate into life outside of the prison walls.” While not upstream solutions, social programs that help families of the incarcerated, particularly the children of prisoners, stand to do much good. Through our events and our scholarship, we are positioned to raise the profile and numbers of these organizations by communicating the real, quantifiable health hazards of incarceration, and the potential that this work—coupled with foundational transformation in our national policy-scape—has to move us to a place where far fewer fathers are incarcerated on Father’s Day.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A. Knox Professor

Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Eric DelGizzo for his contributions to this Dean’s Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: https://www.bu.edu/sph/tag/deans-note/

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.