‘Front Row Seat to Advocacy’ For Alzheimer’s Patients.

Jennifer Weuve, associate professor of epidemiology, helped create the recently released Alzheimer’s Association 2016 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures report.

Jennifer Weuve, associate professor of epidemiology, helped create the recently released Alzheimer’s Association 2016 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures report.

The Alzheimer’s Association releases the Alzheimer’s Association Facts and Figures each year with updated information and a special report delving into a particular issue.

Weuve, whose cross-disciplinary and collaborative research focuses on the determinants and public health burden of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia, has contributed to the last five reports.

When the Alzheimer’s Association first invited her to revise the annual report in 2010, Weuve says she declined. The association asked if she would help find other experts to work on it. “I love creating teams,” Weuve says. “So I said, ‘Let me see if I can do this.’”

In addition to recruiting epidemiologists, caregiving scientists, and economists to write and update sections of the report, Weuve assisted these and the association’s experts in editing for clarity for a readership spanning both those who work in the field and the lay public. She also contributed content to the report, including writing the section on risk factors for the disease.

Weuve recently discussed the new report, and the picture it paints of the tremendous burden of Alzheimer’s.

Q: What’s new in the 2016 report?

A: The newest thing, what’s essentially new every year, is the special report. The focus of the special report here is a bit of an amalgam of what gets reported on caregiving and the cost of caring for someone with Alzheimer’s.

The Alzheimer’s Association conducted a survey of people who contribute to covering the cost of caring for a loved one, either a friend or a relative, with Alzheimer’s disease. They might be caregivers or they might just be helping out in a financial way. What the survey revealed was that the financial burden is not only large—which we already knew—but it had a significant impact on the way that that person has financial options in other parts of their lives. A substantial number of care contributors have cut back on the money they spend on food. Some of them reported that they eat less or that they were going hungry. Some of them report spending less on their child’s education.

The average cost to a care contributor was more than $5,000 of their own money, and for some families this is a burden they can handle, but for lower-income families this isn’t a trivial amount at all, which certainly explains why these other decisions to cut back are being made.

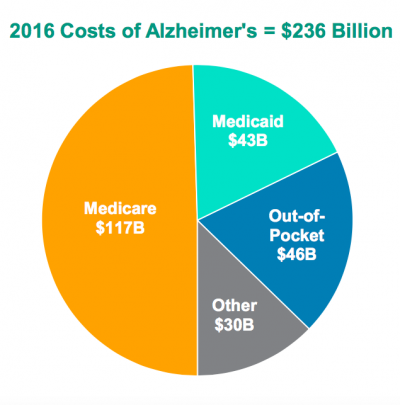

The costs to Medicare and Medicaid are enormous, about $160 billion—and that excludes the cost to caregivers, by which I mean the people who are not formally paid, trained clinicians, but the loved ones, the family members. In 2015 there were more than 15 million of them. They delivered about 18 billion hours of unpaid care, because some of them are on the clock all the time, and even at a measly wage of $12.25 an hour that care is valued at more than $220 billion dollars. It’s a pretty sobering number.

Q: The report also updates facts and figures each year. What are some standout numbers—or changes to numbers—in the 2016 report?

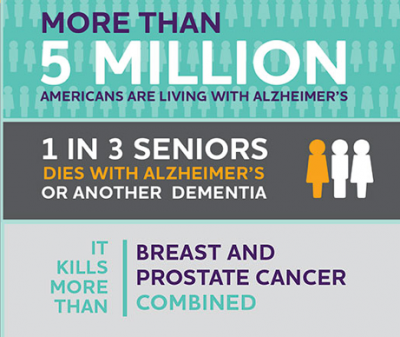

A: This year’s document reports that about 5.4 million Americans have Alzheimer’s disease in 2016.

That estimate is not from Medicare data, it’s actually from a study my colleagues and I conducted in which we evaluate every participant in a systematic way to determine whether or not they have Alzheimer’s. This is a substantial advance over relying on medical records because it ensures that everyone gets evaluated, and not only does everyone get evaluated but they get evaluated in the same way. Many people don’t get diagnosed: When you’re a very sick old person it might be clear to someone that you have Alzheimer’s disease but you’re there [seeing a healthcare provider] for some other reason, and it’s not their job that day to work you up for dementia. This estimate comes from a very different, and we think more reliable, place than just going into Medicare claims and counting.

The other figure that’s updated this year is the incidence of dementia. We estimated that approximately 476,000 people 65 and older will develop dementia in 2016. Take that with a grain of salt: Developing Alzheimer’s disease is something that goes on over a decade, so this is about how many people will reach that threshold of impairment where someone could determine that they have Alzheimer’s.

The other salient fact is that the number of people who die from Alzheimer’s disease has gone up. Other causes of death have been going down: HIV thankfully has been going down as a cause of death, as had cardiovascular disease. But the number of deaths from Alzheimer’s disease is going up, and that’s striking.

Using death certificates to determine deaths from Alzheimer’s disease is woefully inadequate, and that’s because a lot of people just don’t get the right assignment of cause of death on their death certificate. Usually by the time someone who has Alzheimer’s disease dies, they may be facing a lot of other very serious medical conditions, and it can be difficult for the person filling out the death certificate to trace the full chain of events leading to that death.

About 85,000 people who died in 2015 had Alzheimer’s on their death certificate as the cause of death—so, a lot—but if we change that definition a little bit and we acknowledge that when old people die they often are facing many health challenges, my colleagues and I estimated that in 2015 700,000 older adults had Alzheimer’s disease when they died. That’s very different from 85,000!

We’re not saying that Alzheimer’s caused those deaths, but it’s an interesting agnostic approach to describing death in a medically complicated situation that views the burden of Alzheimer’s disease on a population from a slightly different angle: the distinction between dying of Alzheimer’s disease and dying with it.

Q: What do you hope will come of this report?

A: The importance of this report is to gain more awareness of and support for people with Alzheimer’s disease and resources for Alzhiemer’s research, both research on the causes of Alzheimer’s disease which hopefully will lead to insight on preventing Alzheimer’s disease, and also to support research on how to care for people with Alzheimer’s disease.

We estimate that if nothing else happens—if we don’t figure out a way to treat Alzheimer’s disease or to prevent it—13.8 million people in the United States will have Alzheimer’s disease by 2050. It’s a tripling of what the prevalence is right now. When you think about the time it takes for scientists to submit a grant, to have their grant reviewed, to do the work, and have that work translate to some sort of intervention, while we’re working on this problem of preventing and treating Alzheimer’s disease we also have to work on how to manage the disease as well.

Q: What do you think (six years after initially turning it down) of working on this report?

A: It’s been an extraordinarily wonderful project to be involved with. Even though the Alzheimer’s Association reached out to me and ultimately to these other scientists, in some ways I feel like we benefit at least as much from this relationship, because we get to keep our fingers on the pulse of the literature, and also because we get a front row seat to advocacy, and to work with this incredible team of government advisors and communicators.

Many researchers don’t often get a window into that entire spectrum. But it affects not only our lives as researchers—because, wow, if there’s more funding allocated to Alzheimer’s research that has a tremendous impact on me and my colleagues—but we also get to see the potential for affecting the public, and that’s pretty exciting.