Healing the Divides.

In my last Note, I shared a personal reflection on the results of last week’s historic election, with thoughts about how our school community can come together to counteract the bigotry and hate of recent months. Today, I would like to discuss the election more broadly, focusing on the forces that enabled a Trump victory, what they reveal about our society, and how public health might lead the way towards a better future.

In my last Note, I shared a personal reflection on the results of last week’s historic election, with thoughts about how our school community can come together to counteract the bigotry and hate of recent months. Today, I would like to discuss the election more broadly, focusing on the forces that enabled a Trump victory, what they reveal about our society, and how public health might lead the way towards a better future.

The 2016 election, long and rancorous, revealed deep divides in American society. The rise of Donald Trump tapped into the anger of a long-marginalized segment of our society. The misogyny on display throughout the campaign demonstrated how far we still have to go in the area of gender equity, and the bitterness directed at Muslims and immigrants sprang from a strain of ugly nativism that is inconsistent with American values, though, sadly, not American history. The divides laid bare by the election remain, however, and must be addressed going forward in order to build a healthier, less hateful world. I would argue that, at core, these divides are a product of the growing social divides in American society. Too long ignored, these divides have created a country where, during what has been in many respects an era of plenty and progress, millions of people can nevertheless feel left behind. The recent election has shown us how quickly this sense of abandonment can become hate, and how easily this hate can spread, as groups turn against each other and civility gives way to obscenity, even violence.

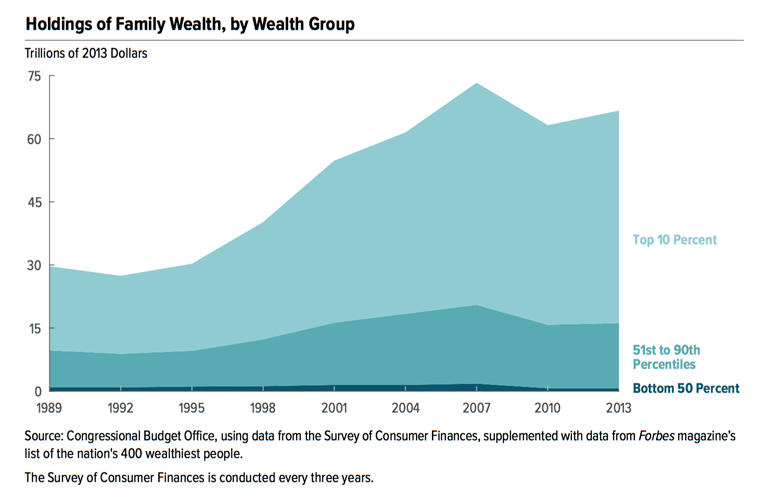

As I have discussed in a previous Note, the anger of the Trump electorate is reflective of the economic and cultural marginalization of the white working class. This marginalization is consistent with the broader economic disparities in the US, as widespread income inequality has become a fact of American life. In Trends in Family Wealth, 1989 to 2013, the US Congressional Budget Office found that, in 2013, 76 percent of all family wealth was held by families in the top 10 percent of the wealth distribution (Figure 1).

Congress of the United States Congressional Budget Office. Trends in Family Wealth, 1989 to 2013. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/51846 Accessed August 27, 2016.

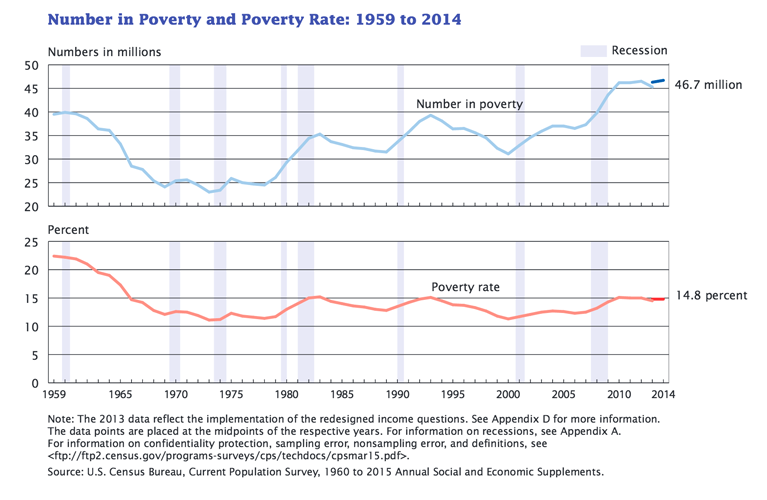

Meanwhile, the US Census Bureau has reported that there were 46.7 million Americans living in poverty in 2014 (Figure 2).

DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2014, Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2015.

There is an inexorable link between poverty and health; I will discuss this in detail in a future Dean’s Note. While overall US life expectancy has increased, lower-income groups have either not shared these gains, or suffered reductions. In 2015 and 2016, politicians in both political parties acknowledged, and capitalized on, the problem of inequality, and the peril faced by economically marginalized groups. This was particularly true in the case of Trump, who made his central appeal to white, working-class voters who felt disenfranchised by the political system. However, rather than working constructively towards solutions, Trump chose a different path, stoking voter anger until it came to define the entire race.

As I discussed in my last Note, the campaign has also shown how far short we have fallen on gender equity. I have written before about how gender equity is a fundamental determinant of population health. It was perhaps inevitable that this issue would be central to a campaign featuring the first woman ever nominated for president by a major political party. However, Trump’s record of misogyny placed the challenge of sexism, and the barriers women face, at the center of the national conversation. Further, Trump’s political resilience in the face of sexual assault allegations, as well as his own admission of committing such crimes, has made it impossible to deny the work still to be done on the issue of gender equity.

Most disturbingly, this year’s atmosphere of hate and distrust has, in some cases, been accompanied by violence. This violence has taken two forms. First, there was the violence that occurred at political events. This violence was perhaps all the more shocking for being unprecedented in modern presidential campaigns, and hopefully represents an aberration, rather than a shift of norms towards the acceptance of such behavior in the future. The second, more serious, form of violence was the seemingly interminable string of hate-inspired shootings we have seen over the last year. These incidents have been tragic for the country as a whole, but especially so for the marginalized minority groups they often target. From the racially motivated shooting last year that killed nine black parishioners in a Charleston, South Carolina, church, to last summer’s Orlando nightclub shooting, which targeted the LGBT community, we have seen, time and again, how hate, along with the ready accessibility of guns in this country, has led to one group lashing out against another, with heartbreaking results.

In bringing these challenges to light, this election has not only reminded us that the forces of bigotry, sexism, and hate still exist—and thrive—in our society, it has also shown us how inequality functions as the root cause of these problems, as well as of the more pernicious threats of violence and political unrest. There will be no narrowing of the country’s health divides without a serious engagement with the social divides that have created a country of health “haves and have nots.” Trump’s rise has also demonstrated how easy it can be to exploit these unequal conditions to promote a discourse that is uncivil and intolerant of different points of view. Indeed, the election has shown us how powerful words truly are, and how they must not be used recklessly or with dishonest intent. This, I think, speaks to what is perhaps the fundamental lesson of the 2016 election—the importance of civility and respect; of engaging with others empathetically, keeping an open mind, as we work towards a healthier society. This is all the more important when the social, economic, and environmental conditions that shape health—our area of focus—appear to be under threat. When this is the case, we must redouble our efforts to meet our core responsibilities, to bear witness through generating knowledge, to train the next generation of public health thinkers and doers, and to act where appropriate to mitigate political action that can harm the health of populations.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A. Knox Professor

Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Eric DelGizzo for his contribution to this Dean’s Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: https://www.bu.edu/sph/tag/deans-note/

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.