Income and Health, Part 2—the Problem of Poverty.

Modern public health has long been concerned with those who live in poverty, and the social, environmental, and economic conditions that shape the lives of the less advantaged. In many respects, modern public health emerged in the mid-19th century, as a direct consequence of the Industrial Revolution. As economies mechanized, widespread urbanization meant that the working classes often lived in close, unsanitary quarters, leading to the spread of infectious diseases like cholera and tuberculosis. To mitigate this problem in England, reformers passed the Public Health Act of 1848, which provided a framework for better sanitation and water quality and established a board of health. These measures, benefitting all, were centrally motivated by the plight of those living in poverty. Edwin Chadwick, one of the key architects of the act, argued that if less-advantaged populations were healthier, they would be less likely to seek government relief, saving money in the long-term. The circumstances surrounding the passage of the act are one of the first examples of how the conditions of poverty, fueled by prevailing economic trends, can drive population health and the broader public health agenda. I suggest that this same impulse needs to fuel much of what we do today as well.

Modern public health has long been concerned with those who live in poverty, and the social, environmental, and economic conditions that shape the lives of the less advantaged. In many respects, modern public health emerged in the mid-19th century, as a direct consequence of the Industrial Revolution. As economies mechanized, widespread urbanization meant that the working classes often lived in close, unsanitary quarters, leading to the spread of infectious diseases like cholera and tuberculosis. To mitigate this problem in England, reformers passed the Public Health Act of 1848, which provided a framework for better sanitation and water quality and established a board of health. These measures, benefitting all, were centrally motivated by the plight of those living in poverty. Edwin Chadwick, one of the key architects of the act, argued that if less-advantaged populations were healthier, they would be less likely to seek government relief, saving money in the long-term. The circumstances surrounding the passage of the act are one of the first examples of how the conditions of poverty, fueled by prevailing economic trends, can drive population health and the broader public health agenda. I suggest that this same impulse needs to fuel much of what we do today as well.

In last week’s Dean’s Note, I touched briefly on a more recent economic trend—the growing problem of income inequality—noting that families in the top 10 percent of the wealth distribution were found to control 76 percent of the country’s aggregate family wealth. While there has been much discussion about this trend in recent years, this conversation has tended to focus more on the excesses of the rich and the decline of the middle class than it has on the rate of poverty in this country—a rate that remains stubbornly high. Today I wanted to focus on poverty as it exists within the context of this inequality, and why, as our public health agenda evolves, a focus on poverty must remain at the heart of our efforts.

There is little doubt that poverty is inextricably linked to health. Over the past 15 years, life expectancy in the United States has increased for middle- and upper-income Americans. However, top earners have gained relatively little ground against the median. This suggests that wealth, for all its benefits, makes little difference in improving health past a certain basic threshold of well-being. In sharp contrast, less-advantaged Americans have seen little or no life expectancy increase, lagging ever-further behind the rest of the population. This difference in life expectancy is explained by a broad range of differences in the lives of those living in poverty compared to those who are not. I have written before about how the assets that less-advantaged populations often lack—education, health insurance, an advantageous living environment—shape health. Education, for example, is an enormously consequential determinant of well-being. Abundant work has shown that education is closely tied to life expectancy and quality of life, with college graduates living at least five years longer than those who do not graduate high school. Lack of educational attainment also drives the risk of disease—both chronic and communicable—and injury. Further, the obesity epidemic disproportionately affects America’s less-advantaged populations. Other examples abound. Driven largely by a lack of affordable, nutritious food, and a wealth of cheap, calorie-rich, nutrient-poor food, this crisis has fueled rates of diabetes, heart disease, and other obesity-related conditions in impoverished communities. Those living in poverty are also more likely to smoke, less likely to breathe clean air, and are subject to all the daily stressors—and attendant mental health problems—of economic insecurity.

Another reason to focus on those living in poverty is that (in addition to the causal link between poverty and health) they are the most likely to face health expenditures that reduce their ability to meet life’s other needs, whether school fees, food, rent, or heat. The epidemic of medical bankruptcy in the US is a salient indicator of this impact. And our inability to create a health system that protects people from health-related financial ruin leads to losses of well-being in other domains, and a vicious cycle of poverty and poor health.

The number of Americans living in poverty remains frustratingly persistent. Before discussing the US poverty rate, it is important to note that the federal government’s 2014 poverty guideline for a four-person household in the 48 contiguous states and the District of Columbia was an income of $23,850 per year. According to the US Census Bureau, there were 46.7 million Americans living in poverty in 2014. This figure, representing 14.8 percent of the population, hasn’t changed much in recent years. The year 2014 represented the fourth consecutive year of the national poverty rate remaining statistically the same (Figure 1). Additionally, between 2009 and 2012, 34.5 percent of the population had at least one period of poverty lasting two or more months.

DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2014, Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2015.

The scale of poverty in the US suggests that vast numbers of Americans live in an entirely different world than those at the top of the economic ladder. Dramatic as this difference is, startling racial gaps that exist within the overall poverty rate are, in their way, just as alarming as the widening gulf between the very rich and the less-advantaged. Among non-Hispanic whites, the poverty rate was 10.1 percent (19.7 million people). Asians had a poverty rate of 12 percent (2.1 million people), Hispanics had a rate of 23.6 percent (13.1 million people), and black Americans had a rate of 26.2 percent (10.8 million people) (Table 1).

![Table 1. People in Poverty by Selected Characteristics: 2013 and 2014 [excerpted from larger table] DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2014, Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2015.](/sph/files/2016/12/income-and-health-part-2-table-1.png)

DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2014, Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2015.

These gaps are indicative of deeply entrenched, structural disparities that persist in this country, independent of macroeconomic trends. Indeed, racial disparities are in many ways symptomatic of the foundational social, economic, and cultural forces—like racism, mass incarceration, and the absence of affordable housing—that have allowed poverty to thrive on a grand scale in the wealthiest nation on earth.

But poverty runs far deeper than merely not meeting a certain financial benchmark. Although the rather narrow federal definition of poverty itself rests on a remarkably low income for a family of four, that seems to barely begin to capture the scope of real poverty. To live in poverty is to be the victim of a complex interplay of harmful factors, lack of income being only one. In their report Five Evils: Multidimensional Poverty and Race in America, Richard Reeves, Edward Rodrigue, and Elizabeth Kneebone identify five principal areas of vulnerability: low income, lack of education, no health insurance, living in a low-income area, and unemployment (Figure 2).

Reeves R, Rodrigue E, Kneebone E. Five Evils: Multidimensional Poverty and Race in America. The Brookings Institution; 2016.

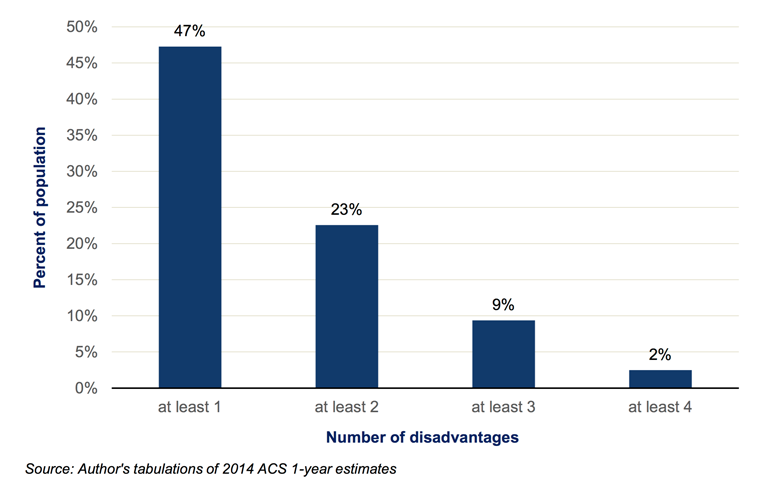

Nearly half of the adult population classified as living in poverty suffers from at least one of these disadvantages, while 23 percent suffers from two or more, 9 percent suffers from at least three, and 2 percent suffers from at least four (Figure 3).

Reeves R, Rodrigue E, Kneebone E. Five Evils: Multidimensional Poverty and Race in America. The Brookings Institution; 2016.

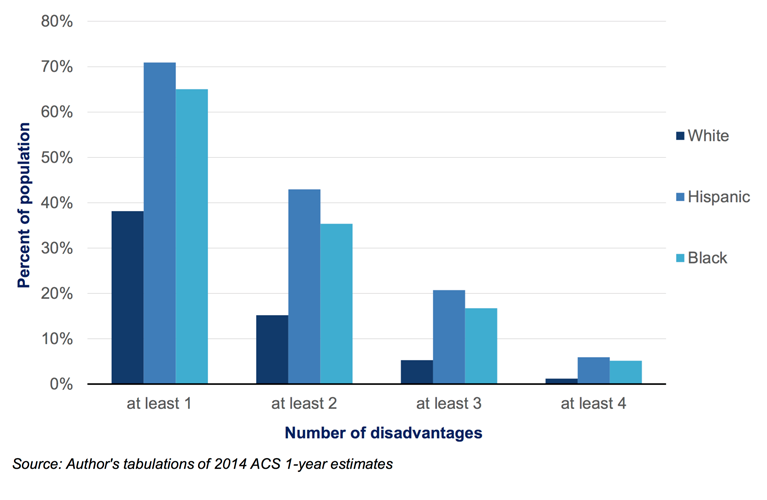

As Figure 4 illustrates, multidimensional poverty affects blacks and Hispanics far more than it does whites, with more than 3 million black and 5 million Hispanic adults experiencing a minimum of three disadvantages.

Reeves R, Rodrigue E, Kneebone E. Five Evils: Multidimensional Poverty and Race in America. The Brookings Institution; 2016.

This combination of disadvantage likewise varies according to race, with some groups more likely to suffer from combined low income, lack of education, and health insurance, while others have a higher chance of experiencing, for example, the triple threat of low income, lack of health insurance, and unemployment (Figure 5).

Reeves R, Rodrigue E, Kneebone E. Five Evils: Multidimensional Poverty and Race in America. The Brookings Institution; 2016.

These disadvantages are reflective of a poverty not merely of income, but of opportunity, stability, hope, and health; a deficit affecting certain races far more than others, and in significantly different ways. This poverty—affecting half of all Americans—seems to me a far more meaningful representation of the disadvantaged in this country, a group that is substantially limited in their assets, and who, as a result, stand to have far worse health than the rest of us.

To my mind, poverty must remain at the heart of the concern of public health. It falls to us to make it clear that present-day poverty, and the unfairness embedded therein, are consequences of foundational inequalities that have long bedeviled our society, favoring certain racial groups over others, even as the country overall remains a land of plenty. The role of public health, then, is to make poverty unignorable; to make the acceptable unacceptable; and to tackle the social, economic, and environmental conditions that allow poverty—and attendant poor health—to persist.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A. Knox Professor

Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Eric DelGizzo, Catherine Ettman, and Professor Jacob Bor for their contributions to this Dean’s Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: https://www.bu.edu/sph/tag/deans-note/

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.