Meeting the Challenge of Obesity.

My thoughts this weekend are with those who were in the path of Hurricane Matthew as it hits the Caribbean and the Southeastern United States. More than 300 people have died as a result of the hurricane in Haiti, and as I write this the hurricane is bearing on Florida. While our thoughts are, as they should be, with those immediately affected by these events, it is also incumbent upon us not to forget the long-tail consequences of disasters, where thousands can be expected to have mental health consequences of these events in months and years to come. I have written on this previously, and we reprint in this week’s SPH This Week a previous Dean’s Note on the topic.

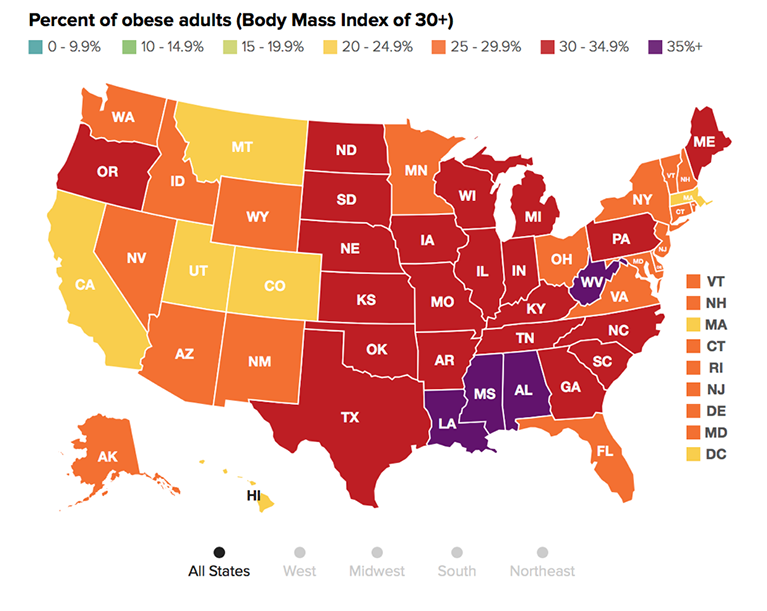

On to today’s note. According to recent data reported by The State of Obesity, obesity rates for adults living in four US states exceeded 35 percent in 2015. The states in question are Louisiana (36.2 percent), Alabama (35.6 percent), Mississippi (35.6 percent), and West Virginia (35.6 percent). They are by no means outliers. Obesity rates have exceeded 30 percent in 25 states and 20 percent in all states (Figure 1).

Making matters worse, disparities that exist within the context of overall obesity rates have made this epidemic particularly devastating for a number of distinct socioeconomic and racial groups. In advance of this week’s World Obesity Day, a note, then, on the challenge of obesity in the US, how obesity disproportionately affects certain groups, and how these inter-group differences are a manifestation of social divides mapping onto health divides, reflecting the power of fundamental causes to shape well-being. These causes, as articulated by Link and Phelan, are characterized by access to, or lack of, resources like wealth and social support. When people have access to these assets, it invariably translates into better health. When they do not, poorer health is often the result, as in the case of obesity and its associated conditions like diabetes, heart disease, and infant mortality. In looking at obesity, we are therefore also looking at the unequal distribution of advantage in our society, and how that inequality drives the presence of health or disease in populations.

Why have obesity rates risen so dramatically? There are a number of reasons. Portion sizes in American restaurants have greatly increased, doubling or in some cases tripling over the last 20 years. Particularly noticeable has been the increase of sugary drink sizes. In the 1950s, the average sugary drink was about seven ounces. It has since grown to an average of 42 ounces. This has ramifications not only for how much we consume when we eat out, but for what we consider to be an appropriate amount of food to consume in a single sitting, even at home. This problem is compounded by the fact that unhealthy foods are frequently more affordable than healthier fare. The affordability of cheap, energy-dense foods is a key driver of obesity among low-resource populations. The ubiquity of fast food restaurants in poorer communities, and the frequent lack of healthy alternatives, also contribute to the rise of obesity. Poorer families looking to improve their diet therefore face an uphill battle against economics, geography, and the social trends that have led over the decades to larger plates for all Americans. It has also become commonplace for high-fat, unhealthy foods to be marketed to children, inculcating unhealthy habits at an early age. It is important to note that these obstacles have little to do with personal choice, or any of the “lifestyle” factors that are so central to American weight loss culture.

As these reasons amply suggest, obesity is closely tied to income and the conditions of poverty. In 2011, more than 33 percent of American adults who made under $15,000 per year were obese, compared with 24.6 percent of those who made at least $50,000 per year. In 2007, 27.4 percent of children living below the poverty line were obese, compared with a 10 percent obesity rate among children with family income that exceeded 400 percent of the poverty threshold (Figure 2).

Lack of education, which is inextricably linked to poverty, also exacerbates the problem of obesity among low-resource communities. Obesity rates for adults who did not graduate high school were about 33 percent in 2011, while adults who graduated from college or technical college had an obesity rate of 21.5 percent. Children of parents who had under 12 years of education had an obesity rate of 30.4 percent, 3.1 times higher than the obesity rate of children whose parents received a college degree (9.5 percent). I will write more about the link between income and educational advantage in a future Dean’s Note.

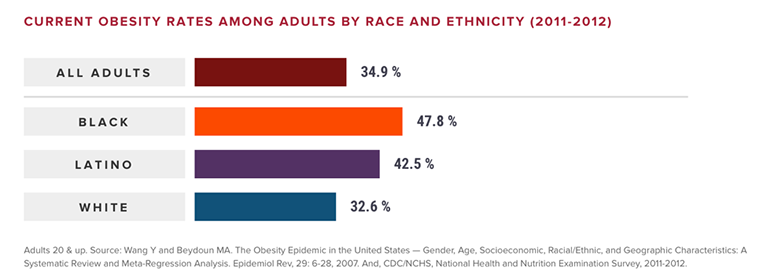

As more Americans become overweight and obese, certain racial groups shoulder a disproportionate burden of this epidemic, driven largely by the higher rate of poverty among these populations. Particularly vulnerable are black and Hispanic/Latino populations, with a poverty rate of 27.4 percent and 26.6 percent, respectively, compared to a 9.9 percent poverty rate for whites. Between 2011 and 2012, compared with an overall obesity rate of 34.9 percent, obesity rates among adults were highest in the black community, at 47.8 percent. Latinos suffered from 42.5 percent obesity, and whites had an obesity rate of 32.6 percent (Figure 3).

The picture shifts slightly when we factor in rates of overweight among adults. Compared with an overall overweight and obesity rate of 68.5 percent, Latinos suffered the greatest burden at 77.9 percent, followed by blacks at 76.2 percent and whites at 67.2 percent (Figure 4).

Latinos also had the highest childhood obesity rates. Compared with an overall childhood obesity rate of 16.9 percent, Latino children had a rate of 22.4 percent, black children had a rate of 20.2 percent, and white children had a rate of 14.3 percent (Figure 5).

Adding overweight to the picture, Latinos had a rate of 38.9 percent, blacks had a rate of 32.5 percent, and whites had a rate of 28.5 percent compared to an overall rate of 31.8 percent (Figure 6).

Obesity is estimated to cost the US between $147 billion and $210 billion per year in healthcare spending, factoring in the expense incurred by obesity-related chronic disease. Despite this vast investment, Americans continue to struggle with obesity. How, then, can we best meet this challenge? I suggest three areas for continued focus. First, changes at the level of policy—specifically a tax on sugary drinks, or the passage of laws that limit the serving size of these beverages. Taking tobacco taxes as a model, taxes on sugary drinks stand to go far towards reducing consumption. And while applying portion controls to sugary drinks has proved controversial in the past, it nevertheless has tremendous potential to curb obesity and improve the health of populations. Second, we must use the challenge of obesity to spotlight the role of economic inequality as an upstream source of health gaps. Given the link between obesity and the conditions of poverty, any attempt to tackle the root causes of obesity must address these conditions, and come to grips with problems like food insecurity and lack of educational access among low-resource populations. We must also push back against stigma by communicating how obesity is less a product of individual failings than it is a consequence of foundational drivers—a case that public health is uniquely positioned to make. Finally, we must situate our efforts against obesity within the broader context of our work to mitigate health inequalities between racial groups. As encouraging as overall gains against obesity are—modest as they have so far been—they mean little if they are not shared across all racial and economic demographics. It lies within the remit of public health to continually point this out, as we move, collectively, towards less obese, healthier populations.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A. Knox Professor

Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Eric DelGizzo for his contributions to this Dean’s Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: https://www.bu.edu/sph/tag/deans-note/

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.