The Public Health Dividend.

Despite spending much more per capita on medical care than other industrialized nations, the US lags behind most of our peer countries in nearly all health indicators; I have commented on this in prior Dean’s Notes. Given this readily apparent discrepancy between our investment and our yield, why have we not invested more wisely in the approaches that would make people healthier?

Despite spending much more per capita on medical care than other industrialized nations, the US lags behind most of our peer countries in nearly all health indicators; I have commented on this in prior Dean’s Notes. Given this readily apparent discrepancy between our investment and our yield, why have we not invested more wisely in the approaches that would make people healthier?

There are several reasons why. There are cultural reasons, i.e., we have a strong over-reliance on the notion of curative medicine at the center of our approach to health, and there are structural reasons, i.e., we, in contrast with many peer countries, have a fragmented approach to governance that does not encourage strategic thinking about investing in non-health policies that promote health. Another reason, however, may be that we, in public health, have failed to make the argument convincingly that an investment in public health yields dividends that far outstrip the initial expenditure. Such an argument establishes investment in population health as both the right financial investment and the smart societal investment. To the end of tackling this issue briefly, today I will address the public health dividend, aiming to articulate how strategic investments in the concerns of public health can provide a real financial return on our investment.

Building on the available evidence, I highlight here three principal areas through which investments in population health yield dividends, moving from proximal to distal: 1) the direct reduction of preventable medical costs and the increase in productivity achieved by eliminating disease; 2) the potential cost reduction achieved by healthcare system strengthening and redesign; and 3) the indirect cost benefits that will emerge through investment in broader foundational factors, such as education and income.

1. Reduce medical costs by preventing disease

First, an investment in improving the health of populations will result in the more proximal savings we experience by averting the costs associated with preventable disease. This is perhaps the most-studied area that is relevant to the question at hand. Savings here can be considered in three separate areas.

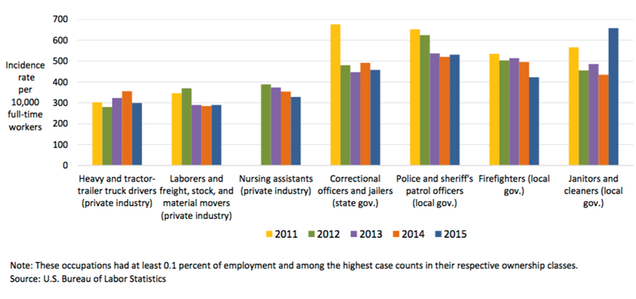

a. Occupational injuries and health. The Department of Labor calculates that businesses in the US spend a combined total of $170 billion per year on costs associated with occupation-related injuries or illnesses, amounting to a substantial strain on corporate yield and profits. Lost productivity alone costs businesses $60 billion per year. In 2015, there were 1,153,490 absent days from work due to occupational injuries reported in private industry and government. As shown in Figure 1, the rates of injuries vary by type of occupation, with police officers, correctional officers, and janitors reporting some of the highest rates.

US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics News Release. November 10, 2016. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/osh2.pdf Accessed June 13, 2017.

Companies that have health and safety management systems in place, however, can reduce these costs by 20 percent to 40 percent. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration, through the US Department of Labor, provides assessments and aid in implementing safety and health management systems, a truly smart investment. A meta-analysis by Baicker and colleagues found that every $1 spent on workplace wellness was associated with a $3.27 decrease in medical costs and a $2.37 decrease in absenteeism costs. This is not just the case for manual labor; one large government organization of desk workers implemented an ergonomics program from 2009 to 2013 and found a return on investment of about $10 for every $1 spent.

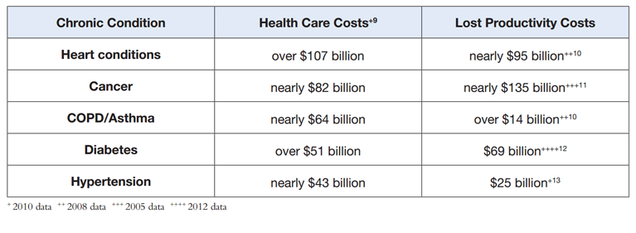

b. Non-communicable disease. Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are responsible for the greatest burden of disease worldwide. NCDs are both largely preventable and incur tremendous costs, both in terms of direct health care expenditure and lost productivity, as can be seen in Figure 2. The five most expensive preventable conditions cost the US about 30 percent of its total health spending in 2010.

Public Health and Chronic Disease: Cost Savings and Return on Investment. American Public Health Association. https://www.apha.org/~/media/files/pdf/factsheets/chronicdiseasefact_final.ashx Accessed June 13, 2017.

Obesity, often a precursor to heart disease, stroke, type II diabetes, and cancer, costs the US about $147 billion annually. Medical costs associated with obesity are expected to continue to increase each year, and related loss in economic productivity is estimated to be $390 billion to $580 billion per year by 2030. Similarly, smoking, which is associated with a host of chronic conditions, cost the US a total of about $193 billion between 2000 and 2004.

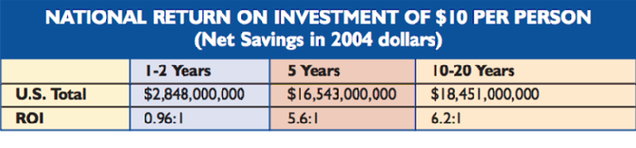

How can interventions here result in cost savings? An analysis by the Milken Institute suggests that the US could potentially lower treatment costs by $218 billion annually, as well as lower the economic impact of disease by $1.1 trillion per year, through investment in the prevention of the most common chronic diseases. A simulation study focusing on colorectal cancer alone found that by improving screening and treatment, as well as by reducing risk factors, the US could save $33.9 billion in reduced productivity loss in 15 years. We can also look to some successful interventions of the past as examples: An analysis of the truth® anti-smoking campaign found that just under $1.9 billion in medical costs was averted as of 2009, attributable to the social campaign, which cost far less to develop and deliver. More generally, an analysis by the organization, Trust For America’s Health, found that each dollar invested in evidence-based disease prevention programs geared towards increasing physical activity, improving nutrition, and preventing tobacco use can save $5.60 in health expenditure within five years, and as much as $6.20 within 10 years, as shown in Figure 3 below.

Prevention for a Healthier America: Investments in Disease Prevention Yield Significant Savings, Strong Communities. Trust for America’s Health. February 2009. http://healthyamericans.org/reports/prevention08/Prevention08.pdf Accessed June 13, 2017.

There are a range of different mechanisms though which chronic disease prevention leads to savings, and interventions to improve health while saving money have been undertaken throughout the globe. For example, an analysis by Rasmussen and colleagues estimated the total lifetime cost savings for society of smoking cessation in Denmark among moderate smokers who quit smoking by the age of 35 years to be 24,800€ for each man and 34,100€ for each woman.

c. Communicable disease. Many of the health gains in high-income countries over the past century arose from our reduction in morbidity and mortality from communicable, or infectious, disease. Communicable disease remains, however, an important burden of disease in the US. For example, in America, 5 percent to 20 percent of the population each year comes down with the flu, resulting in an $87 billion economic loss. The most obvious example of successful public health investments in the area of communicable disease is that of vaccinations. In the US, universal routine vaccination of hepatitis A is estimated to result in an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $21,223 per quality-adjusted life-year. The CDC estimates that hospitalizations avoided and lives saved through the Vaccines for Children Program, begun in 1994, will save the US upwards of $295 billion in direct costs, and $1.38 trillion in societal costs. Another analysis estimated that vaccinating children born in 2009 led to savings that, by 2020, could reach $13.5 billion in treatment and $70 billion in other societal costs, including lost productivity costs. This return on investment is particularly salient given recent setbacks in vaccination rates and concomitant outbreaks.

2. Reduce US health expenditure through investment in nimbler, more efficient health systems

Second, the health of the public is dependent on strong systems that preserve and promote health. This is an area where the US has long fallen short. Yet, we do know how we can implement better systems that can save lives and money. The implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) is a recent example that, while difficult to measure, is estimated to result in $2.1 trillion less spending on medical services, medications, and devices by 2019, compared to pre-ACA estimates. This is, of course, if the ACA stays in place. The release this week of information about the new Senate healthcare bill is disappointing indeed in this regard.

At the state level, the New York State government saved $17.1 billion in federal dollars through its Medicaid Redesign Team reforms. Simply investing in public health departments can produce savings; for example, the return on investment for $1 in county departments of public health in California is estimated to be between $67 and $88.

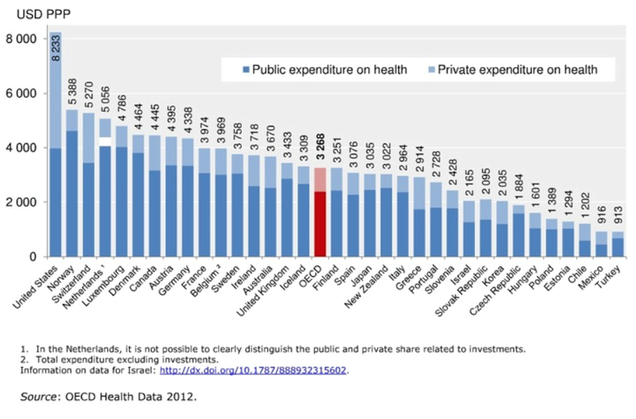

Perhaps the most helpful lessons in investment at the systemic level come from our peer countries. As one can see in Figure 4, we in the US spend far more than our peer countries, and 2.5 times the average of Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, on health, per capita. This expenditure is partially due to over-testing and over-treating conditions. For example, in the US, there are more than twice the number of MRI and CT tests ordered per 1,000 people, compared to the average among OECD countries. Cutting down on unnecessary procedures is a smart investment when viewed through this lens.

Kane J. Health costs: How the US compares with other countries. PBS Newshour. October 22, 2012. http://www.pbs.org/newshour/rundown/health-costs-how-the-us-compares-with-other-countries/ Accessed June 13, 2017.

Bentley and colleagues created a schematic, as illustrated in Figure 5, that depicts different levels of waste in the US health care system. For example, they estimated that overuse of noninvasive radiologic imaging wastes $36.044 million to $65.099 million per year, and excessive use of antibiotics for viral infections wastes $525 million to $546 million per year.

Bentley TGK, et al. Waste in the US health care system: A conceptual framework. The Milbank Quarterly 2008; 86(4): 629—659.

We have seen how the public health dividend has paid off elsewhere in the world. A recent Dean’s Note focused on Sweden as one example of how a national approach to strengthening health systems and public health has resulted in not only a healthier public and a more equitable society, but also in lower costs.

3. Tackle the true costs of the social, economic, and environmental drivers of disease

Finally, I have long argued that foundational factors should be considered within the purview, and indeed at the heart of, public health, recognizing the many links between social conditions and health. It is then germane to consider the dividends that we may accrue through investment in foundational factors such as education, fostering income equality, and community revitalization. Unfortunately, this is the area where the data are weakest, even as it would stand to reason that the public health dividend here would likely be significant.

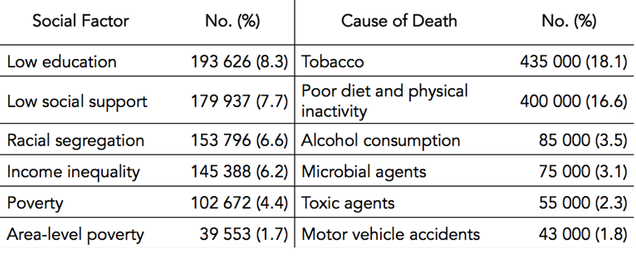

By way of tackling this area, Figure 6 is derived from a paper our group published a few years ago, where we estimated that the number of deaths that can be attributed to social causes such as low education, low social support, or racial segregation are comparable to those attributed to the leading proximal risk factors or causes of death in the US.

From: Galea S, Tracy M, Hoggatt KJ, DiMaggio C, Karpati A. Estimated deaths attributable to social factors in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2011; 101(8): 1456—1465.

Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual Causes of Death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004; 291 (10): 1238—1245.

It follows, then, that an investment in, for example, education—both at the individual level and societal level—both improves population health and has economic implications, through direct and indirect routes to health. These investments can be in a range of economic and social structures that would contribute to the promotion of health and the prevention of disease. For example, poverty and income inequality are inextricably linked to health indicators. Efforts to close gaps between the rich and the poor, such as increasing the minimum wage or expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit benefit, would likely result in better health and more overall savings; one recent analysis estimated that if the minimum wage were increased to $12 per hour by 2020, anti-poverty programs could save $17 billion per year. Again, we may look to many of our peer high-income countries that have more equitable income distributions, as well as better health outcomes.

Then there is the environment. The health effects of poor environmental quality are well-documented, and have been so for centuries. Research into 19th century European cities and the discovery of the link between water quality and cholera—considered by many to be the birth of modern epidemiologic methods—have shown us how sanitation efforts drastically improved the heath of populations. More recently in Europe, an estimated 8.7 million disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) have been lost in young children as a result of outdoor air pollution. In the US, filtration and chlorination of water in the early 20th century is estimated to have yielded a return of more than 23 to 1. More recently, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that the Clean Air Act, enacted in 1970 and amended in 1990, has had a benefits-to-cost ratio of more than 30 to 1 by improving air quality and emissions, resulting in better health and economic welfare. This past progress, combined with recent threats to the EPA, has serious implications in today’s America. Zooming further in on the effect of the built environment on health, investments in housing have substantial financial benefits. For example, a recent analysis found that every dollar invested in lead paint hazard control in the US results in a return of $17 to $221 per dollar, or $181 billion to $269 billion overall.

In sum

The US spends more on health, and has far poorer health, than any of its peer high-income countries. That is in no small part because we mis-invest our resources, spending far more on medical and curative care than we do on the conditions that can prevent or promote disease. We have done so for decades, to the detriment of the health of populations. It is the responsibility of public health to change this state of affairs, providing the evidence and making the argument as clearly as possible that an investment in population health is the right investment. Available data are robust about the dividends that accrue when we prevent medical costs and increase productivity through preventing disease—the core function of public health. We shall require substantially more evidence to make the case clearly and compellingly that investment in broader foundational factors compound these dividends, saving money as we promote population health. Scholarship that aims to fill this gap stands to make a sentinel contribution to the national conversation.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A. Knox Professor

Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful for the contributions of Laura Sampson, Matthew Kim, and Catherine Ettman to this Dean’s Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: https://www.bu.edu/sph/tag/deans-note/