Homelessness and Health.

A core aim of public health is to care for the most vulnerable members of our society—the marginalized and the dispossessed. At this festive season, when friends and family gather together, and “abundance rejoices,” it seems to me especially important that we focus on these vulnerable groups—people who find themselves excluded from the resources and community ties that generate health. For this reason, we will run a “trilogy” of Dean’s Notes on the conditions that create this marginalization, starting this week with homelessness. The goal is to inspire reflection this holiday season on the vulnerable populations whose challenges are a central concern of public health.

A core aim of public health is to care for the most vulnerable members of our society—the marginalized and the dispossessed. At this festive season, when friends and family gather together, and “abundance rejoices,” it seems to me especially important that we focus on these vulnerable groups—people who find themselves excluded from the resources and community ties that generate health. For this reason, we will run a “trilogy” of Dean’s Notes on the conditions that create this marginalization, starting this week with homelessness. The goal is to inspire reflection this holiday season on the vulnerable populations whose challenges are a central concern of public health.

Homelessness is a persistent, visible health challenge in the US. While we are fortunate to have many programs dedicated to caring for the homeless here in Boston, including the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program—an organization we honored, along with its founder Jim O’Connell, at our recent gala—we nevertheless are daily confronted by the problem of homelessness. The US Department of Housing and Urban Development conducts an annual count of homeless people in the US, and found an average of 564,708 people living on the streets per night in January 2015. This number had declined overall in the preceding years (651,142 people were homeless in 2007), but increased in various places, importantly in New York City, where about 14 percent of the national homeless population resides. Figure 1 below shows changes in homelessness nationally in recent years.

The state of homelessness in America 2015. http://www.endhomelessness.org/library/entry/the-state-of-homelessness-in-america-2015

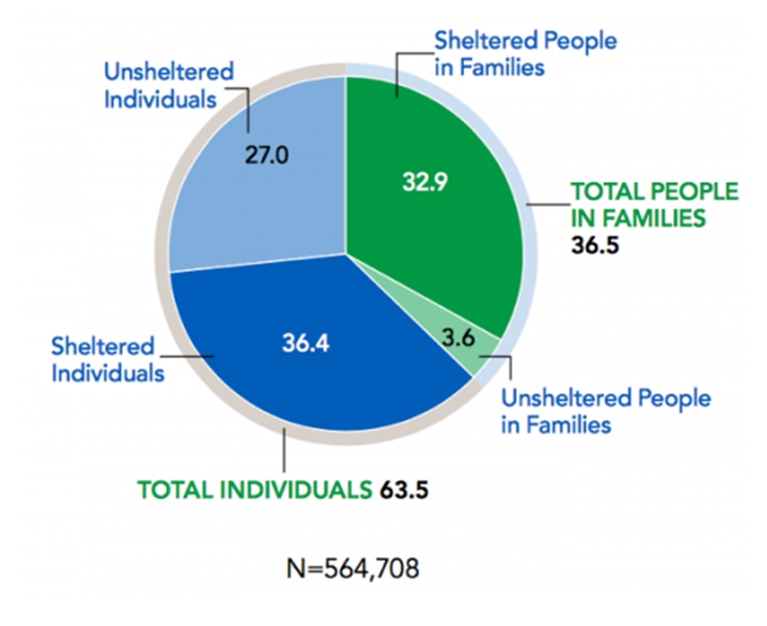

The majority of homeless people are only considered homeless for a short time, but a sub-population of the homeless are chronically homeless for 30 to 40 years. In a 2015 count, 83,170 individuals and 13,105 people in families with children nationwide had either been continuously homeless for a year, or experienced at least four episodes of homelessness in three years. Furthermore, 36 percent of all homeless individuals were part of families with children. This is shown in Figure 2.

The 2015 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress. The US Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Community Planning and Development. November 2015. PART 1: Point-in-Time Estimates of Homelessness. https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2015-AHAR-Part-1.pdf

There is abundant evidence about the health consequences of homelessness. At a fundamental level, the homeless have higher premature mortality than those who are appropriately housed, with injuries, unintentional overdose, and extreme weather events being important drivers of this mortality. The homeless also have poor quality of life, characterized, as noted in various studies, by chronic pain associated with poor sleeping conditions and limited access to medications and other salutary resources. Skin and foot problems, dental problems, and chronic infectious diseases are also well-described among homeless populations. For a comprehensive review of the health of the homeless, I would refer to this published work.

The intractability of homelessness—we all know that homelessness is a challenge, and that it threatens health—presents challenges both to how we think of homelessness and its consequences, and how we might envision solutions. Perhaps one useful frame is to consider homelessness across the lifecourse, by way of highlighting the factors that are coincident with, and contribute to, homelessness.

Twenty-three percent of the homeless population in the US is under the age of 18. Homeless youth are especially vulnerable to drug use; one study found that 55 percent of street youth and 34 percent of shelter youth have used illicit drugs since leaving home, compared to 13 percent of youth who’ve never been homeless.

Importantly, and signaling one of the central contributors to homelessness, a sample of homeless adolescents in Los Angeles showed that 32 percent reported a need for help with mental health problems and 15 percent met criteria for emotional distress. The proportion of those with emotional distress was higher among gay, lesbian, or bisexual youth as well as black youth. It has been estimated that roughly three times as many homeless adolescents suffer from depression compared to other adolescents. Homeless adolescents are also likely to experience violence: 21 percent to 42 percent report sexual abuse, compared to one percent to three percent of the general population, and about 40 percent have reported being assaulted with a weapon. About 40 percent identify as LGBT.

As with youth, homeless adults are also at greater risk of substance use disorders and overdose compared with the general population. They are also very likely to smoke tobacco. Homeless adults are disproportionately affected by psychiatric disorders, though it is difficult to estimate the true burden among this population, considering they are usually excluded from national surveys. Homeless people with mental illnesses tend to have less contact with family or friends and are more likely to remain homeless for a longer time period.

Older individuals are at risk of being homeless later in life due to lack of income. Specifically, those younger than 65 years old who do not yet receive Medicare or social security benefits and are unemployed may be especially vulnerable. Additionally, older veterans make up a large portion of the homeless population, although the proportion of veterans who are homeless has decreased since 2009. In January 2015, 47,725 veterans were considered homeless on a given night.

Therefore, homelessness is overwhelmingly coincident with socioeconomic vulnerability and with poor behavioral health, both mental illness and substance use. Which leads to the approach we might consider taking to mitigate the consequences of homelessness. Much of the literature in the area suggests that interventions that provide case management for substance use and mental illness and critical time intervention approaches to mitigate the consequences of acute stressors can be effective in reduction of homelessness. However, these approaches rest on health care and interventions embedded in health care systems. They do not, however, obviate, nor supplant, the centrality of approaches that tackle the social policies and structural factors—including absence of affordable housing and of social safety nets that target vulnerable and low-income individuals—that ultimately set the conditions for homelessness and unstable housing for marginalized populations. For anyone interested in hearing more about the topic, I recently had the privilege of hosting a conversation about it at an event for our alumni in Toronto. The event is archived here.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A. Knox Professor

Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful for the contributions of Laura Sampson and Eric DelGizzo to this Dean’s Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: https://www.bu.edu/sph/tag/deans-note/