The Future Is Urban, Global, and Unequal.

Viewpoint articles are written by members of the SPH community from a wide diversity of perspectives. The views expressed are solely those of the author and are not intended to represent the views of Boston University or the School of Public Health. We aspire to a culture where all can express views in a context of civility and respect. Our guidance on the values that guide our commitment can be found at Revisiting the Principles of Free and Inclusive Academic Speech.

Viewpoint articles are written by members of the SPH community from a wide diversity of perspectives. The views expressed are solely those of the author and are not intended to represent the views of Boston University or the School of Public Health. We aspire to a culture where all can express views in a context of civility and respect. Our guidance on the values that guide our commitment can be found at Revisiting the Principles of Free and Inclusive Academic Speech.

Cities occupy a special place in our popular imagination. Think of any number of movies set, evocatively, in some of the world’s most prominent cities. London, New York City, and Tokyo may come to mind as the backdrop of many a romantic or action film. Cities are exciting, dynamic places, populated with a broad range of humanity, where many languages are spoken and food from all over the world is readily available.

And yet, depending on one’s perspective, cities are also unsettling. They are places with higher crime rates than small areas, where change happens quickly, upsetting hard-fought status quo, where newcomers have to fight to earn their place. Cities are also characterized by deep inequalities, where extreme wealth often exists side by side with destitution that would not have been out of place centuries ago.

And these pictures, varied as they are, all represent aspects, sometimes contradictory, but all equally true of cities. Given the omnipresence of cities in our lives, it may be worth pausing to understand the nature of cities, and how they will shape our world going forward.

1. More people live in cities than ever before.

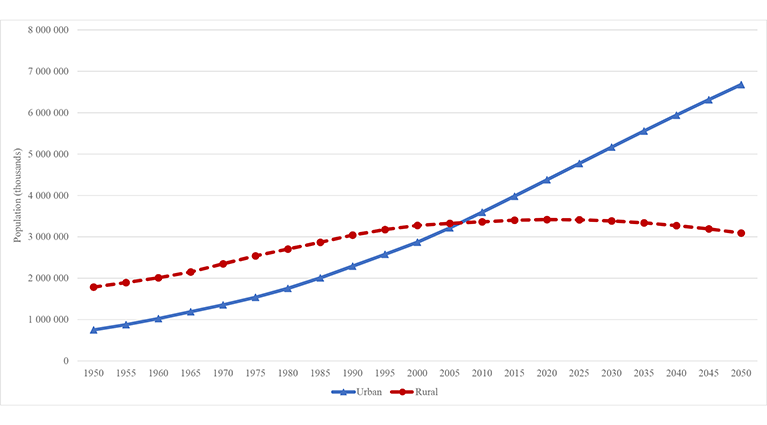

The proportion of people living in cities has increased dramatically during the last century. At the turn of the 20th century, approximately 10 percent of people lived in cities. By 1950 about 29 percent of the world’s population lived in cities. As seen in Figure 1, by 2007, more than half of the world’s population lived in cities, and it is projected that by 2050 68 percent of the world will live in cities. In absolute terms, between 2000 and 2014, 1 billion additional people were added to cities, and the world’s urban population is expected to grow from 2.86 billion in 2000 to 4.94 billion in 2030.

There is, then, little doubt that the future is urban. More people today live in urban rather than rural areas, and this trend will continue to increase for the foreseeable future.

2. The future of cities is global.

While cities in the Western hemisphere have long captured the cultural imagination, the majority of urban populations live outside of North America. Indeed, as shown in Table 1, in terms of absolute populations, the population of urban dwellers in Asia exceeds the number of people living in urban areas in all other continents combined.

Table 1: Urban populations by continent, 2015

| Continent | Population | Percent of total global urban population |

| Asia | 2,119,873,000 | 53% |

| Europe | 547,147,000 | 14% |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 505,392,000 | 13% |

| Africa | 491,531,000 | 12% |

| North America | 290,616,000 | 7% |

| Oceania | 26,938,000 | 1% |

| Total | 3,981,498,000 | 100% |

Source: Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World urbanization prospects: the 2018 revision. New York, NY: United Nations; 2018. Table 1 has been revised with updated figures for population estimates across continents.

In the decades ahead, the largest cities will all be in Asia and Africa. Table 2 shows the top five largest urban agglomerations in the world from 1950 through 2025. In 1950, three of the five largest cities were located in the Western Hemisphere (New York-Newark, London, and Paris). By 2025, none of the five largest urban agglomerations in the world will be in the Western Hemisphere. We would expect that our narrative on cities will in time shift east, as cities in this part of the world begin to make up most of the global population.

Table 2: The five largest urban agglomerations ranked by population size at each point in time, 1950-2025

| 1950 | 1975 | 2000 | 2025 | |||||

| Rank | City | Population (millions) | City | Population (millions) | City | Population (millions) | City | Population (millions) |

| 1 | New York | 12.34 | Tokyo | 26.61 | Tokyo | 34.45 | Tokyo | 37.04 |

| 2 | Tokyo | 11.27 | Osaka | 16.30 | Osaka | 18.66 | Delhi | 34.67 |

| 3 | London | 8.361 | New York | 15.88 | Mexico City | 18.46 | Shanghai | 30.48 |

| 4 | Osaka | 7.01 | Mexico City | 10.73 | New York | 17.81 | Dhaka | 24.65 |

| 5 | Paris | 6.28 | São Paulo | 9.61 | São Paulo | 17.01 | Cairo | 23.07 |

Source: Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World urbanization prospects: the 2018 revision. New York, NY: United Nations; 2018.

3. The urban experience is unequal.

The experiences of urban dwellers differ greatly within cities. In many cities, those with the highest amount of wealth within a particular country live side by side with those with the lowest. Striking scenes of inequality are common in cities across the world.

Take by way of example the city of Seattle. There is a gap of more than 18 years in life expectancy for men and 14 years in life expectancy for women between neighborhoods within King County, a difference driven by disproportionate burden of a range of diseases—from heart disease to lung cancer—borne by the poorer segment of the population. As another example, David Hulchanskihas suggested that there are three “cities” within Toronto, changing rapidly, moving further apart, with high-income and low-income groups increasing and middle-income groups shrinking.

Contributing to intra-urban inequality is faster population growth in low-income countries than in high-income countries. By 2050, 1.1 billion people will live in urban areas in high-income countries, 4.8 billion people will live in middle-income countries, and 700 million people will live in urban areas in low-income countries, as shown in Figure 2.

Accompanying the growth of urban populations in low-income countries is increasing urban poverty. As such, global poverty s becoming more and more of an urban phenomenon in recent years, with the absolute numbers of urban poor increasing at a rate faster than that in rural areas over the last 20 years. By 2050, close to 2 billion people will live in slum-like conditions in urban areas if current circumstances remain unchanged. The availability of wealth and material resources among rich urban dwellers, compared with the increasing numbers of urban poor is, in turn contributing to more dramatically different lived experiences, making for an ever more unequal urban future.

Why health?

Given that the majority of the world’s population now lives in urban areas, and given that urban environments shape what we do, how we do it, what we consume, when and what we play, and generally how to behave, two observations emerge. First, cities will increasingly shape our health in coming decades, and second, the very ubiquity of cities makes them important forces to reckon with as we think about the health of populations.

There are several published frameworks that can teach us how cities can be both health promoting and reducing. At a Dean’s Symposium hosted at the School of Public Health on December 6, scholars from around the world will come together to discuss the state of the science around urban health and the various ways that cities shape health, aiming to further sharpen our thinking in this area.

Cities shape, and are going to shape ever more of, our human experience. Understanding that the urban exposure is increasingly ubiquitous and focusing our attention on where urban growth is happening can help us in our work to improve the health of populations.

This piece is a modified excerpt from Urban Health (Galea S, Ettman C, Vlahov D, eds., Oxford University Press, forthcoming 2019).

Catherine Ettman is chief of staff and director of strategic development at SPH and is pursuing a PhD at Brown University School of Public Health in the Department of Health Services, Policy, and Practice.