Why Racism Undermines the Health of the Public.

Last Thursday, in an Oval Office meeting with lawmakers, President Trump is reported to have made a derogatory statement about immigrants, and their places of origin. White House sources say the context for the remarks had been the President expressing frustration at the US protecting immigrants from Haiti, El Salvador, and Africa. Trump reportedly expressed his desire for the US to instead accept more immigrants from places like Norway.

The racial implications of these statements are clear. Haiti, El Salvador, and Africa are known for being home to many people of color, whereas Norway less so. Trump suggested that the US should be more welcoming to immigrants who are white, at the expense of immigrants who are not. This needs to be called, unequivocally, what it is: racism.

While the President has since denied making these comments, they are consistent with his past statements and actions. I have written previously about how the racially divisive policies of the Trump administration threaten health. They mainstream cruelty, and shift our culture away from attitudes that support the well-being of communities and the dignity of individuals. We have also seen how racism can threaten populations globally, creating conflict in places like Myanmar, and political unrest across Europe and elsewhere.

For these reasons, racism, divisiveness, and hate are intolerable, both in the US and globally. To promote health, we must reject racism and the language that encourages it, even when that language comes from the President of the United States.

There is an abundance of evidence for how racism can undermine health by marginalizing racial minorities, subjecting them to a range of daily stressors and even violence. For a closer look at these hazards, we are today running a modified version of a prior Dean’s Note on the public health effects of racism. We do this as part of our commitment, as a community, to join with voices that denounce racism, to move our society closer to the day when we decide such attitudes are no longer acceptable, either in our leaders or in ourselves.

How should we, in the academic public health community, think about racism and the health of populations, and about our responsibility to tackle this issue towards a healthier public?

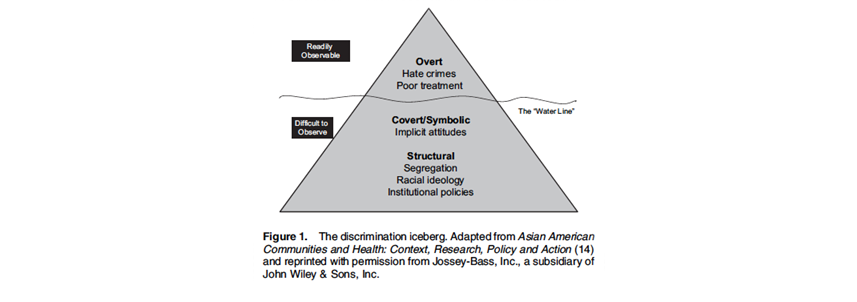

While there are many ways in which we can consider the impact of racism on health, it may be useful to think of racism’s impact on two levels: interpersonal or individual racism, and structural or institutional racism. There is ample evidence of the impact of racism on health in both domains, and the iceberg metaphor serves to illustrate the distinction between the more readily observable (i.e. interpersonal) versus the more difficult to observe (i.e. structural) dimensions of racism [see Figure 1]. Informing our understanding of how discrimination, both interpersonal and structural, can contribute to health inequities and how to test such hypotheses, Nancy Krieger provides a useful conceptual model [see Figure 2].

Gee G. C., Ro A., Shariff-Marco S., & Chae D. (2009). Racial discrimination and health among Asian Americans: Evidence, assessment, and directions for future research. Epidemiol Rev, 31(1), 130-151. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19805401

Starting with interpersonal racism, there is ample evidence that self-reported racism is associated with poor health. Interpersonal racism can operate through physiologic response mechanisms and/or unequal quality of care, including implicit racial bias. The most consistently studied and observed positive associations are for markers of poor mental health (i.e. emotional distress, depression symptoms) and health-related behaviors (i.e. smoking, substance use), findings robust to adjustment for potential confounding. Negative physical outcomes have been reported on far less, and findings have been more inconsistent, but positive associations have been found for cardiovascular risk factors and poor birth outcomes, to name two examples. Findings have been similar among youth, although greater evidence has emerged for a negative relation between self-reported racism and positive mental health outcomes (i.e. self-esteem, resilience) relative to adults. Studies of racism and health have expanded in recent years to include cancer as an outcome, offering further evidence for such links over relatively long disease induction periods. For example, Teletia R. Taylor, along with SPH professors Yvette D. Cozier, Julie R. Palmer, and Lynn Rosenberg, found that perceived racial discrimination was related to elevated breast cancer risk among black women, particularly among those who were younger and experienced racism in multiple forms (i.e. housing, job, and police-related).

Krieger N. (1999). Embodying inequality: A review of concepts, measures, and methods for studying health consequences of discrimination. Int J Health Serv, 29(2), 295-352; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10379455

Moving on to institutional and structural racism, evidence exists that there remain substantial institutional barriers to fair and equitable medical treatment, and that this subpar treatment is associated with poorer health. Much of the work on structural or institutional discrimination has centered around residential segregation and unequal access to health care. For example, a geographically weighted regression approach demonstrated that residential segregation was associated with black/white differences in coronary heart disease mortality. A recent analysis demonstrated a beneficial effect of the end of Jim Crow laws (i.e. legal discrimination) on the reduction of premature mortality for blacks, accounting for age, period, cohort, state, and county income effects; a related analysis demonstrated a similarly beneficial effect on the black infant mortality rate. Critically, however, there is a striking dearth of research on institutional and structural racism relative to the now large body of work on interpersonal racism.

What, then, is our responsibility, as members of an academic school of public health community, to engage this issue? I would argue that we have a responsibility on four levels.

First, we are, at core, engaged citizens of our local and global communities. In that capacity, some of us may choose to participate in public shows of support with affected communities, ensuring that this issue rises to the top of the public conversation, and stays there. Peaceful public statements of concern about a pressing social issue always have a place in an open society, and our responsibility as members of society is not obviated by our membership in our academic community.

Second, we are members of a university community. Generation of knowledge is the primary responsibility of universities, and the generation of relevant knowledge that can help inform acute social needs is the particular remit of professional schools. This nudges us towards a scholarship of consequence, where, in this particular instance, we aim to shed light on the root causes of the racial divides that are informing the public debates of the moment, and of the link between racism and the health of the public. This of course suggests a concern with prioritizing our research questions, focusing, as I have argued, on what matters most, and orienting our scholarship towards areas of inquiry that tackle the foundational drivers of population health.

Third, we are charged with transmitting knowledge to students, with education that both teaches the foundations of our field and prepares students to engage in evolving issues of contemporary public health importance. That calls for an education that is dynamic and reflexive, but also an educational environment that encourages and respects sharing of ideas, towards the goals of engendering mutual understanding and identifying solutions grounded in diversity of experience, opinion, and perspective. It is simply not enough to accept that our educational program is rooted in concern around issues of disparities; we need to engage in hard, sometimes uncomfortable discussions about these issues in order to understand one another and our potentially different perspectives on challenging issues. As a school, we are working towards creating the forums for such discussions and embedding formal education on this in our program.

Fourth, translation of our ideas is one of our core responsibilities as a school of public health. Insofar as public health rests on the generation of conditions that make people healthy, and insofar as those conditions depend on the introduction of health in all policies and in all sectors, we need to work towards a health conversation that extends well beyond our academic walls. We need to engage with the public conversation that aims to inform and influence how we understand racism and its consequences, to better understand the health consequences of racism, the pathways that explain these links, and how these links may be broken. Needless to say, racism and hate of any kind are intolerable separate from their health consequences. But health, as a universal aspiration, can serve as a clarifying lens for action, as one more tool to elevate the import of these issues in a public conversation that in the end aspires to create a society that indeed makes populations healthy.

I aspire indeed to meeting these responsibilities together.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A. Knox Professor

Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I would like to acknowledge the help of Gregory Cohen, MSW on this Dean’s Note and the comments of Associate Dean for Education Lisa Sullivan that helped shape my thinking in this Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: https://www.bu.edu/sph/category/news/deans-notes/

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.