Some Gun Violence Risk Factors Are Visible from Space.

Gun violence is an incredibly complex issue, with a seemingly endless array of causes. But city governments usually see reducing gun violence as a matter of policing, says Jonathan Jay, assistant professor of community health sciences. Policing isn’t a complete solution, Jay says, because even if a city has the policing resources, it doesn’t address those myriad underlying issues. And in black communities, which bear the overwhelming majority of gun violence, more policing can also cause harm.

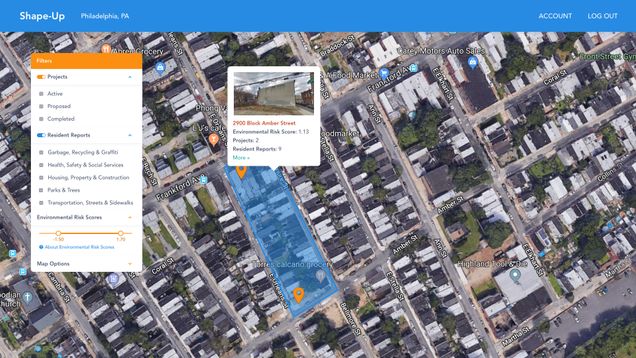

Enter Shape-Up, a new project led by Jay, which recently won the $100,000 Everytown for Gun Safety Prize and was named a Solver with MIT Solve.

Shape-Up is a web application designed to help city governments identify and prioritize areas where a fairly simple physical improvement, such as turning a vacant lot into a little park or tearing down an abandoned building, can actually reduce gun violence. Shape-Up uses a machine-learning system trained on gun violence data and satellite imagery to identify—down to the city block—which areas are at the greatest risk of gun violence. The platform combines the satellite image analysis with data from 311 calls from community members identifying specific issues they want to see fixed in their neighborhoods.

“What we aim to do here is show city governments that they could be directing resources they’ve already got—and which are often directed towards higher-income neighborhoods first—towards reducing gun violence,” Jay says.

“It’s a manageable step that shows that this is not a completely overwhelming problem—which isn’t to minimize the problem, but rather to show that there are effective steps you can take right away.”

Jay is developing Shape-Up with the Software & Application Innovation Lab (SAIL) at BU’s Hariri Institute for Computing. He also credits Elaine Nsoesie, assistant professor of global health, for her work pioneering this particular approach of machine learning with satellite imagery and public health data.

Shape-Up’s gun violence prevention strategy is based on research—including one study led by Jay—finding that steps to reduce physical blight in a neighborhood can reduce nearby gun violence by 11 to 29 percent.

Jay says the simplest explanation for this is that removing physical blight also removes an easy place to sell drugs or stash guns. “Importantly, though, these studies have all looked for displacement, whether violence just goes from the place that you’ve cleaned up to an adjacent place, and that has not been found,” he says.

“Many researchers think that there is a more powerful social explanation, which is that when you clean up spaces, neighbors are more likely to spend time outside, get to know each other, and feel a sense of ownership,” Jay says. “Even having more eyes on the street makes it harder to commit violence in those spaces.”

Jay cautions that much of the research on this strategy has taken place in areas with more housing than demand, such as in Detroit and North Philadelphia, rather than in places—such as Boston—where gentrification is rampant. “It’s important that we’re talking about ‘remediation,’ bringing places up to a basic livable standard, as opposed to the most extravagant beautification,” he says. “It’s not a dog park. It doesn’t tell you that Starbucks is coming. It just removes the hazard.”

Shape-Up is about community ownership, Jay says, which is why it includes “those 311 complaints, what residents have actually asked for,” rather than simply relying on algorithms and satellite images. “It really, really matters how community members perceive conditions,” he says, and the satellite image analysis is ultimately to supplement what community members already know and are already demanding to make their neighborhoods safer and more livable. “This is a method that can reinforce this understanding in a way that is systematic and statistical, and can show these block-by-block differences very starkly,” he says.

Beginning in early 2020, Jay will run a pilot of Shape-up in Albany, NY, working with city agencies and community partners to improve and test the platform.

“In the short-term, I hope Shape-Up contributes to cities understanding that they can reduce gun violence through achievable steps that make neighborhoods safer, cleaner, and greener,” Jay says. “In the long-term, I hope it contributes to a sense that every neighborhood deserves the same level of investment from the government and private sources, and that every kid growing up in a city deserves to walk down safe blocks and have the same chance to succeed.”