COVID-19 Testing May Be Missing Harder-Hit Communities.

As much of the country begins to reopen after months of lockdown, states and counties are using local COVID data to inform their plans. But a new Boston Children’s Hospital analysis co-authored by School of Public Health doctoral students highlights an inconvenient truth: Geographic access to COVID-19 testing sites is as uneven as access to health care overall, so local estimates of COVID-19 spread may be incorrect.

As much of the country begins to reopen after months of lockdown, states and counties are using local COVID data to inform their plans. But a new Boston Children’s Hospital analysis co-authored by School of Public Health doctoral students highlights an inconvenient truth: Geographic access to COVID-19 testing sites is as uneven as access to health care overall, so local estimates of COVID-19 spread may be incorrect.

The peer-reviewed study, published in the Journal of Travel Medicine, found longer travel times to COVID test sites in rural counties and in counties with more people of color and/or more uninsured people, suggesting that COVID cases are potentially under-counted in these areas.

“We’re only seeing a very small sliver of information about this epidemic, and we know that some of that information is biased,” says study-co-lead author Benjamin Rader, a doctoral student in epidemiology at SPH and a graduate research fellow in the Computational Epidemiology Lab at Boston Children’s Hospital.

That information bias may be throwing off policy, but it also means people who could have worse outcomes from contracting the coronavirus face barriers to finding out that they have it, says study co-author Reese Sy, also an epidemiology doctoral student at SPH.

“Our main finding was that travel time to testing was longer in counties with lower population density,” she says. “Other studies have shown that, even though there might be less disease transmission in rural areas, these areas also have older populations who potentially have more comorbid conditions. Barriers to testing only compound this issue.”

But they also found inequities in more densely-populated areas: Communities of color—who structural inequities make more likely to have comorbid conditions that make the coronavirus especially dangerous—had longer travel times for a COVID test than did majority-white communities, even after adjusting for median income.

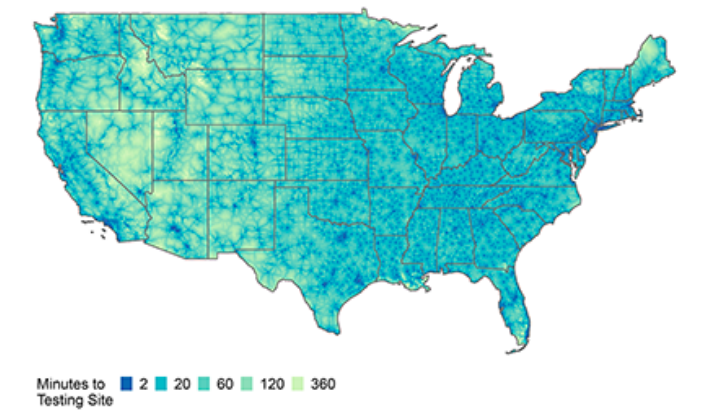

The researchers used two national databases to identify more than 6,000 coronavirus testing sites. Then, with a previously published, high-resolution map of travel times, they calculated how long it would take people in every county of the contiguous United States to get to a testing site.

Although a lot of media coverage around testing has focused on the drive-through locations that state and local governments have set up during the pandemic, the researchers found that these accounted for only 3 percent of COVID-19 test sites as of early April. Most sites were affiliated with either medical centers (43 percent) or urgent care providers (47 percent).

In other words, Rader says, testing was originally set up using existing health care infrastructure—so the communities with less access to health care also have less access to testing.

Across the board, areas with less health insurance coverage tended to have longer travel times. But, while more sparsely-populated areas naturally had longer travel times to testing sites than did densely-populated areas, the researchers found that the association between uninsurance and longer travel was particularly pronounced in rural counties. “The people in these counties have a double hit: Not only are they traveling farther, on average, because they live in a rural area, but also because they don’t have health insurance,” says the study’s other co-lead author, Christina Astley of the Computational Epidemiology Lab at Boston Children’s Hospital, an attending physician in the Division of Endocrinology at Boston Children’s Hospital and an instructor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School.

The researchers also noted that some travel times would likely be longer than they estimated, because of inequities in transportation.

Rader and Sy are involved in several other studies identifying how the place where someone lives in the US affects their risks around COVID-19, and how these disparities are driven by longstanding racial and income inequalities.

One of these studies, led by Sy, used New York City subway ridership patterns to analyze how race, class, and Tessential work have affected the spread of COVID-19.

Rader is involved in several follow-ups to the testing access study, with the goal of better understanding the relationships between geography, testing, infection, and disease outcomes. “We’re really interested in connecting these things,” he says. “If you have worse access to testing, does that show up in outcomes? Does that mean we are undercounting disease in some communities? This is an area of research that we are hoping to pursue further.”

The two doctoral students came to SPH planning to study infectious diseases, but could never have guessed the unprecedented pandemic they now research.

With so much still unknown about COVID-19, Rader and Sy say that students like them, early in their doctorates, can hopefully make a real difference.

“What really motivates me is just being able to help in any way that I can, and add to the scientific literature in any capacity,” Sy says. “We’re just trying to piece things together to gain a more cohesive picture of the pandemic.”

COVID-19 is also teaching a brutal lesson on the role that policy and health systems play in how an epidemic unfolds. “As the disease progressed in the United States, we learned more and more that even if you understand everything about the disease—which we still don’t—there are still really important dynamics in how our response will affect outcomes,” Rader says.

This testing site study is case in point. “In designing a COVID-19 response framework, we risk incorporating the existing biases found in our health care system,” he says.