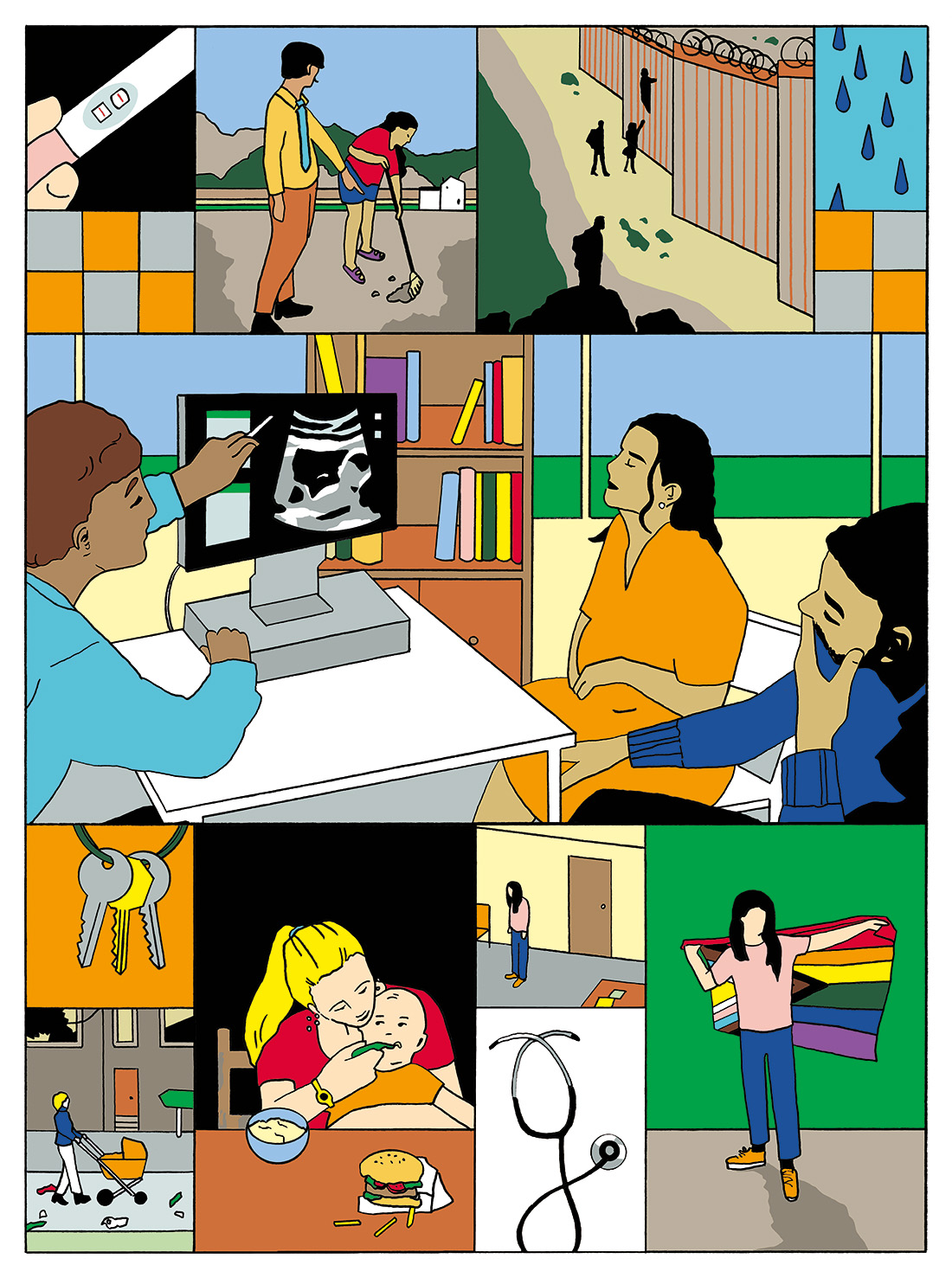

A Broader Mission: Improving Health for All, Not Just for Some.

Illustration: Fien Jorissen, Heart Agency

A Broader Mission: Improving Health for All, Not Just for Some

Along with its toll of lives taken too early, the pandemic highlighted many of the substantial gaps in multiple systems that influence the health of society’s most vulnerable populations. These groups —the poor, the elderly, the disabled, young mothers and children—historically bear the heaviest burdens of disease.

Our collective experience over the past three years has shown us that interventions to reduce health inequities often fall short of achieving their intended goals, in part because many require broad policy changes that are beyond the reach of public health.

But what if public health can take a leadership role in assessing policies that improve at least some of the social determinants of health? Where would we see the benefits first?

Maternal and child health continues to be one of the areas poised for a substantial increase in improved health outcomes, in part because the current situation is so bleak.

For example, Candice Belanoff, a maternal and child health epidemiologist and clinical associate professor of community heralth sciences, found that despite ongoing findings and interventions, racial inequities in preterm birth continue to widen in the United States, affecting non-Hispanic Black babies at nearly twice the rate of non-Hispanic White babies.

People come to the US from all over the world, carrying with them not only their own individual life experiences and exposures, but often intergenerational trauma from the legacies of colonization and enslavement.

A key to why this gap endures can be found by talking a closer look, as Belanoff did in this study, at the specific individual backgrounds and circumstances of the birthing parents having pre-term babies. She and her team found the prevalence of preterm birth among Black immigrants varies widely by region and country of origin, and those who are foreign-born are less likely to have a pre-term birth than their US-born counterparts.

“The importance of disaggregating health inequities data wherever possible cannot be overstated.” writes Belanoff. “People come to the US from all over the world, carrying with them not only their own individual life experiences and exposures, but often intergenerational trauma from the legacies of colonization and enslavement. These are the factors we need to examine if we hope to understand racial inequities in perinatal outcomes.”

Structural Inequities Run Deep

Julia Raifman, an assistant professor of health law, policy & management, uses observational data to study how policies drive disparities in population health. Researchers are able to use this information to study the dynamics of a disease as it progresses through a population, as well as related aspects of health outcomes. Prior studies coauthored by Raifman found that decades of structural inequities in education, employment, housing, stress, and other factors have shaped disparities in the burden of chronic diseases by race, ethnicity, and income.

Institutional policies play a large role in creating or exacerbating health inequities, and thus can play an important role in combatting them, says Lois McCloskey, associate professor of community health sciences and director of the School’s Center of Excellence in Maternal and Child Health. Maternal health, and the Black and Native maternal health crisis in particular, present a glaring example of the effect institutional policies can have on some populations.

“While there are deep underlying reasons for the threefold higher rate of maternal deaths among Black and Native mothers in the U.S.—namely longstanding multi-level structural racism—there are also reasons that can be stemmed at the institutions where pregnant people come for care before, during and after pregnancy,” McCloskey says. “There are ample data and stories to remind us of how the failure of providers to listen to mothers and treat them with dignity and respect can lead to preventable death and ‘near misses.’”

Among the disturbing stories are the birthing experience of tennis star Serena Williams and the postpartum death of public health officer Shalon Irving. Williams suffered dangerous blood clotting immediately after delivering her baby, yet her concerns were initially downplayed by medical staff. Three weeks after giving birth, Irving collapsed and died from complications of high blood pressure.

Both women had the educational and financial means usually associated with healthy outcomes, yet each may have been subtly affected by what McCloskey terms the “cultures of disrespect” that Black and Native mothers in the U.S. often face in medical settings. McCloskey believes reducing this as a cause of inequity will likely require policies that support and require longitudinal training programs in antiracism and equity in maternity care, involving the accountability of providers through patient-derived metrics.

A Policy of Respect and Understanding

Representation matters, which is why another institutional policy lever to fight inequity may be mostly administrative: hiring and supporting providers who reflect a patient’s gender, race and ethnicity, culture, and language, McCloskey says. “We know that concordance, having similar backgrounds and identities between patients and providers, is associated with better satisfaction with care, quality of care, and better health outcomes.”

Achieving any of this will likely be more difficult with the changes to reproductive health access in many parts of the country in the wake of the Dobbs v. Jackson decision that overturned Roe v. Wade. All are under threat at this moment in time, McCloskey says, and where one lives determines how serious the damage will be.

McCloskey points out the importance of viewing the loss of abortion rights within a reproductive justice lens, a framework introduced in the 1990s by organizations founded and led by women of color “in response to the failure of the reproductive rights movement to acknowledge the historic and current absence of choice in the reproductive lives of women of color,” adding, “Reproductive justice calls us all to consider the essential human rights that should govern the ability of one to choose to have a child or not have a child, and to raise children in safe and health environments so they can thrive.”