Antibiotic Misuse in India Could Exacerbate Drug Resistance.

Antibiotic Misuse in India Could Exacerbate Drug Resistance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a global public health threat that directly caused 1.27 million deaths, and contributed to nearly 5 million more deaths, in 2019 alone—more than HIV/AIDS or malaria.

Antibiotic resistance, in particular, has accelerated the spread of bacteria known as “superbugs,” which place an immense strain on health systems and economies, and result in increased hospitalizations and deaths. Globally, India tops the list of countries with the highest antibiotic consumption, and highest AMR.

Inappropriate use of antibiotics is one of the central drivers of AMR, and this misuse or overuse of drugs remains a significant problem in India—with stark differences in consumption rates across states, according to new research led by School of Public Health researcher Shaffi Fazaludeen Koya (SPH’22).

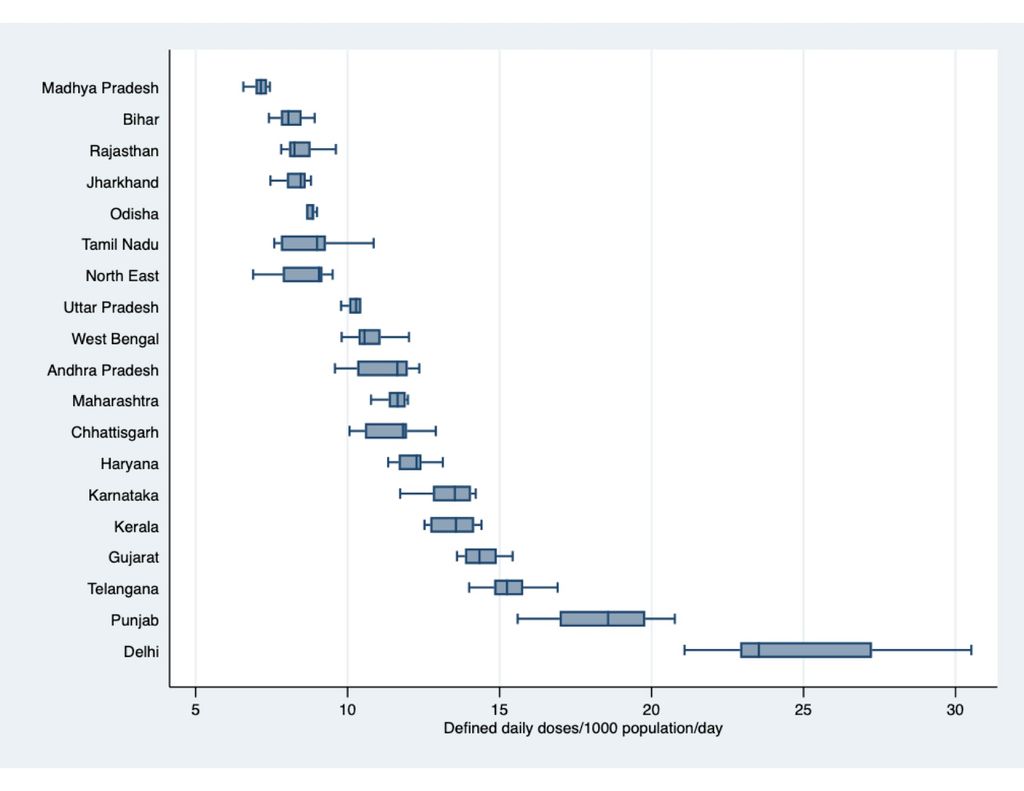

One study, published in The Lancet Regional Health—Southeast Asia, examined antibiotic use in India and found that the country consumes a high volume of broad-spectrum antibiotics—drugs that treat a wide range of common bacterial infections and should ideally be used sparingly—as well as unapproved formulations of drugs. A subsequent study, published in the journal JAC—Antimicrobial Resistance (JAC-AMR), analyzed antibiotic consumption at the state level in India, and found that there are significant variations in antibiotic misuse across the country, with low-income states and states with poor health indicators reporting the lowest consumption rates.

This high volume of private-sector antibiotic consumption is largely due to unrestricted drug manufacturing, marketing, and sales in India, underscoring the need for the government to strengthen regulations around antibiotic production and distribution, the researchers say.

“India has a huge problem of inappropriate antibiotic consumption and this trend has been consistent or worsening over the past several years that we examined,” says Koya, research fellow in the Department of Epidemiology.

One main reason behind the inappropriate use of antibiotics in many low- and middle-income countries is the lack of effective regulations, or failure to implement those regulations, Koya says. “India—which is the largest producer of medicines in the world and supplies medicines to the US and other high-income countries, and to several low-middle income countries—does not have an effective drug quality surveillance system. The country has one central regulator and 28 state-level regulators that share powers and responsibilities. Existing regulations are obsolete and many times allow different standards and quality systems for drugs that get exported, versus drugs consumed domestically.”

Past research across countries have shown that, too often, clinicians prescribe antibiotics when they are not required, or they prescribe the wrong antibiotics to patients. Other times, pharmacy staff are not fully qualified to sell these medicines, or they sell them without prescriptions, all of which can lead to AMR if patients consume the wrong drug or dosage, and for the wrong duration.

The Lancet Regional Health paper is the first to analyze private-sector antibiotic consumption in India using a “defined daily dose” metric, as well as the World Health Organization’s Access, Watch, and Reserve classification, which categorizes more than 180 antibiotics based on their optimal use and potential for AMR. For the study, Koya and colleagues obtained nationally representative data of private drug sales and examined antibiotic consumption based on the AWaRe classification, essential drug classification, product type, and federal approval status. While the findings showed that per-capita antibiotic consumption declined from previous estimates, they also showed that unapproved drugs constituted nearly half (47.1 percent) of that consumption.

But what is particularly worrying, says Koya, are the vast differences in the consumption patterns and levels of inappropriate use between states and regions in India.

“These differences largely contrast the expectations based on disease burden,” he says. “As our second study in JAC-AMR shows, states which have higher infectious disease burden have shown relatively lower per capita consumption rate compared to states with lower infection burden. Moreover, some of these “high focus” states—the group of states which have a poorer health infrastructure and health indicators as per government classification—show worsening trends in the inappropriate use of antibiotics.”

The JAC-AMR results did indicate appropriate antibiotic use in some states that have consistently increased their public spending in healthcare, but overall, the findings from both studies “demand careful review of prevailing policies and systems at the highest political leadership of the government,” Koya says.

“As the ‘world’s pharmacy,’ India has a huge responsibility to ensure the quality of drugs exported,” he says. “India needs a better central regulator—something similar to the US Food and Drug Administration.”

He also calls on India to provide adequate funding and resources to state regulators for drug product approval.

“This is very critical, as these state regulators currently lack sufficient capacity, technical staff or expertise, or other resources to carry out production site inspections, decide on the technical merit of an approval application, and review the evidence submitted by companies, and there is hardly any transparency in the process followed,” Koya says.

At SPH, both studies were co-authored by Veronika Wirtz, professor of global health, Sandro Galea, dean and Robert A. Knox Professor, and Peter Rockers, associate professor of global health.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.