Is There a ‘Right’ Definition of PFAS?

Is There a ‘Right’ Definition of PFAS?

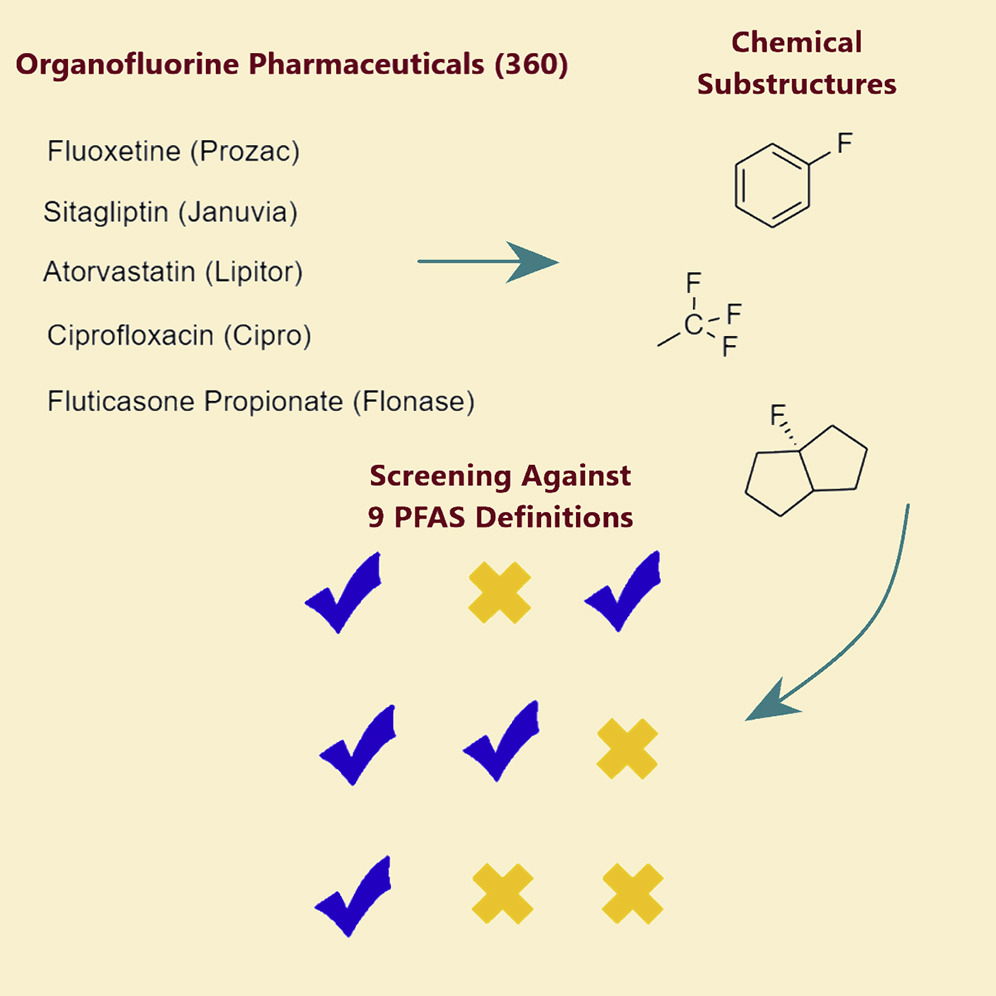

Regulatory agencies and other groups have adopted varying definitions of PFAS, or “forever” chemicals. Many of these definitions are broad, and could include drugs such as Prozac and Lipitor in the classifications.

Hundreds of life-saving drugs, such as the cholesterol-lowering Lipitor, anti-depressant Prozac, and new COVID-19 antiviral treatment Pavloxid, contain organic fluorine, a compound often used in pharmaceuticals to reduce drug side effects and enable the medicine to work longer. Organic fluorine is also a key element of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)—a group of manufactured chemicals found in an array of consumer and industrial products such as nonstick cookware, food containers, and cleaning products. Dubbed “forever chemicals” because they are difficult to break down, PFAS are linked to air and water pollution, as well as increased cholesterol, cancer, and decreased vaccine response in children.

Because these life-saving drugs contain organic fluorine, these medicines fall under one or more of multiple definitions of PFAS put forth by US regulatory groups and non-governmental organizations, according to a new study led by School of Public Health researchers.

Published in the journal iScience, the first-of-its-kind analysis applied nine different PFAS definitions to a comprehensive list of organic fluorine drugs and found that the definitions presented conflicting interpretations of how the drugs could be categorized.

There is no universal definition for the thousands of unique PFAS chemicals that exist, and researching and regulating each individual substance is impractical. Instead, regulatory groups and non-governmental organizations have developed their own definitions of PFAS that combine the PFAS chemicals into groups in order to measure PFAS prevalence and usage, monitor health effects, and develop regulatory action.

Some of the PFAS definitions are broader than others, with the broadest PFAS definitions encompassing hundreds of organofluorine drugs, including Lipitor and Prozac. The findings underscore the need for groups to reach a consensus on the most appropriate and useful PFAS definition, because how researchers and policymakers define PFAS will determine how chemicals that fall under these classifications are monitored and regulated.

“Our study takes a close look at how PFAS definitions differ from one another, and examines how PFAS regulation policies apply to organic fluorine pharmaceuticals,” says study lead author Emily Hammel (SPH ’20), a doctoral student in the Department of Environmental Health. “For this group of compounds, the definitions offer different and conflicting views of what is and is not ‘PFAS.’ Also, some definitions are ambiguously written and have multiple interpretations. The policies that are borne from these definitions could have substantial implications for how essential pharmaceuticals are regulated, so the language matters.”

Using the nine definitions prepared by various stakeholders, Hammel and colleagues screened 360 organofluorine pharmaceuticals approved and used globally between 1954-2021, which, in addition to Prozac and Lipitor, include the common drugs Flonase, Crestor, Cipro, Diflucan, and Paxil. Under each definition, the researchers determined how many drugs were classifiable as PFAS. Depending on whether definitions were broad or narrow, anywhere from 1 to 100 percent of the drugs they analyzed could be categorized as PFAS.

So what is the “right” definition of PFAS? The researchers say it depends on how a definition is being used; i.e., the reason and environment in which organizations are tracking and analyzing PFAS. The study provides a framework against which organizations can make clear decisions on how to best define PFAS depending on the purpose and the circumstances of their research.

“A broad definition for PFAS may be beneficial in some scenarios, but problematic in others,” says study senior author Wendy Heiger-Bernays, clinical professor of environmental health. For example, she says, organizations interested in monitoring PFAS in the environment may be interested in organofluorine pharmaceuticals and their breakdown products. “We don’t know very much about how pharmaceuticals degrade once they leave the body. If we used a definition of PFAS for environmental monitoring that was broad enough to include some of these pharmaceuticals, it could be a great opportunity to better understand how organofluorine chemicals behave in the environment.”

However, banning PFAS in consumer products using a definition that includes dozens of pharmaceuticals poses a significant problem, since many of these drugs are considered essential. “Depending on the context of the definition, it may be useful to make exceptions for specific uses,” Heiger-Bernays says.

A universal definition for PFAS would be ideal, but may not be practical, Hammel says.

“The reality is that this is a very large class of chemicals used in a variety of applications, and there may not be a universally useful definition,” she says. “The real danger is not adopting any definition, for fear of not having a perfect definition, and the consequential delay in decision making.”

The study was co-authored by Thomas Webster, professor of environmental health at SPH, and Rich Gurney, co-chair and professor of chemistry and physics at Simmons University.