A Caregiving Chasm: Professor Reflects on the Shortcomings of the US Healthcare System.

A Caregiving Chasm: Professor Reflects on the Shortcomings of the US Healthcare System

In a candid Q&A, Jennifer Beard, clinical associate professor of global health, discusses her personal battle to secure long-term care for her ailing mother, as explored in her recently published essay “The Idea of a Good Daughter.”

Today, one in five Americans—an estimated 53 million people—care for an older, sick, or disabled loved one, often sacrificing sleep, income, educational and professional opportunities, and their own health to do so. Thrust into the role of caregiver by a healthcare system that fails to offer families long-term alternatives, many feel that they have no choice.

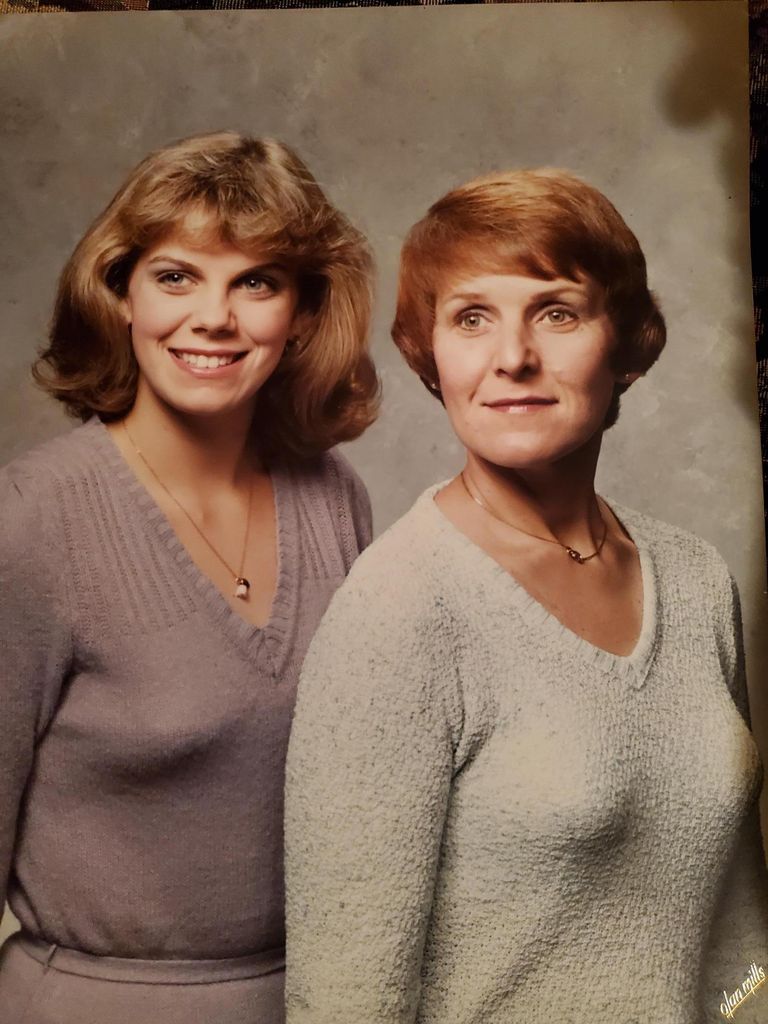

In an essay recently published in Health Affairs, the leading journal of health policy research, Jennifer Beard shares her own experience navigating what she terms “the long-term care chasm” after her mother was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer and discharged home after surgery with complex care needs. “The Idea Of A Good Daughter” tells the story of how the US healthcare system let down Beard, a clinical associate professor of global health, and her mother, Irene Bogacki Beard, during a time of crisis.

Beard had just over a year to mourn the deaths of her father, John Myron Beard, and her only sibling, her brother John Michael Beard, when she learned her mother had cancer. By that time, it had spread to her mother’s bowel and spine, and while surgeons unblocked her bowel, she needed a catheter placed in her chest for total parenteral nutrition, or TPN, before she could leave the hospital. With her eyesight failing and no one else living at home to help her operate the machine, Beard’s mother needed an in-home health assistant, something Beard quickly learned neither private insurance nor Medicare would pay for if the patient could rely on someone in their life who was “teachable,” never mind if that person lived and worked hundreds of miles away in another state. Beard faced a demoralizing choice: care for her mother herself at home in Ohio or maintain the life and professional career she had built over decades in Boston.

![Irene Bogacki Beard beams at the camera. She has white hair and wears a black shirt. An orange wall stands behind her.]](/sph/files/2024/12/20210409_181928-1024x768.jpg)

At Boston University, Beard is the associate editor of Public Health Post, a daily population health magazine written by SPH students and public health researchers; the director of SPH’s Public Health Writing Program, the home of the peer writing coach program and an array of other writing resources; co-director of the BUMC Narrative Writing Program, a writing community designed to give faculty and staff the opportunity to practice narrative skills; and the founder of the BU Program for Global Health Storytelling, a collaboration between SPH, the BU College of Communication, and the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

She spoke with SPH about her writing process, her essay’s key message, and the role narrative writing plays in good public health communication.

Q&A

With Jennifer Beard, Clinical Associate Professor of Global Health

What motivated you to pen this essay about you and your mother’s experience navigating the US healthcare system?

Over the last five years, I have been increasingly interested in writing narrative essays and creative non-fiction in general. When my mom got sick in May 2021, everything happened so quickly. I was in a state of continual motion for several months. After she died in late August 2021, writing seemed like a good way to slow down, to think about what had happened, and what had not happened. It was also a nice way to spend time with her [memory]. The essay has taken many forms since I started, [but] it has always been a mix of personal experience and research, so I wasn’t sure I would ever find a home for it. Then, I learned about Health Affairs’ “Narrative Matters” section, where it was ultimately published.

Was there a particular moment when it occurred to you that your story might resonate with other people?

Before my experience, I knew nothing about long-term care. The image of the “[long-term care] chasm” is something that evolved as I was working on the essay. I had been thinking about our experience for a couple of months. Then I enrolled in a two-day workshop facilitated by the OpEd Project and I started freewriting. I shared my ideas in a Zoom room with one or two other participants, and they encouraged me to keep going. Many people I talked to have shared stories about their own experiences caring for family members, sometimes for years. I couldn’t shake the thought that we were all at risk. Someone we love will need assistance someday, and so will each of us.

Neither your mother’s experience as a nurse nor your expertise as a public health professor were of any significant help in navigating the US healthcare system during her health crisis. As I read your essay, I felt like I was learning about the system’s shortcomings along with you. What is your perspective on the current state of public health communications and how could narrative writing play in a role in improving understanding of public health challenges?

We now recognize a lot of the things that went wrong during the pandemic, and we talk about building trust a lot more. When Rochelle Walensky came [to BUSPH] and spoke in March 2023, she talked about the communication breakdowns at the CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] and why people lost trust [in the agency]. This is an important and useful public conversation, but little seems to have changed within academia. The goal is still: write long sentences in highly technical jargon and do your best to publish in a peer-reviewed journal. And then don’t worry about whether or not people who are not experts will understand it. I would love to see equal emphasis placed on writing for a broad audience and publishing on non-academic platforms.

We do a good job at BUSPH. We have a great communications team filled with people who have expertise in public health, and because we have things like Public Health Post. Dean Sandro Galea has been a champion who often models this kind of writing. And the same is true for incoming Interim Dean Michael Stein. We have the BUMC Narrative Writing Program, but we need more faculty and staff from the School of Public Health to participate. Maria Glymour, [chair and professor of epidemiology], is in the current cohort, and each year we might have one or two applicants from SPH, but the participants are mostly clinicians. They have patient experiences, which lend themselves to writing narratives. But we [in public health] have stories to tell too. And they do not have to be stories within our area of scholarly expertise. We can and should write about our interactions with the world around us and relate them to topics we study and teach.

How did your experience editing Public Health Post influence the approach you took in writing your own essay?

One of the things I love about working for Public Health Post is that we truly care about trying to write in a more accessible way. I have been the associate editor at PHP since 2018. I read nearly everything we publish several times, both the work of our [student] fellows and the work of our guest authors—scholars from all over the country and sometimes even the world—who we invite to write for us. I spend many hours each week reading work by people who are translating complex scientific articles for readers from many professional and educational backgrounds. This kind of writing is incredibly difficult to do, especially in 300 to 600 words. Each article goes through multiple rounds of feedback and revision. The opportunity to edit all of this work has helped me hone my writing process and voice.

In your essay, you suggest that a “cultural fixation on family responsibility” and reliance on women’s largely unpaid domestic labor is holding the country back from achieving a well-functioning system of social welfare for the modern age. How do you think family dynamics have changed in the U.S. and how have these changes exacerbated inequities?

I am not married. I do not have kids. Both by choice. I had two or three paragraphs up until the last draft that I ended up cutting because I thought maybe this is a different article. They were about how there are a lot of us, at least in my generation and younger, who have decided not to get married, not to have kids. But I read these stories in The New York Times and the Boston Globe that say we are creating a growing public health crisis of aging, kinless, childless adults. We should not be expecting young people to take care of us. We want them to love us and be in our lives, but to burden them with caring for us (often without assistance) is just wrong.

I have a paragraph where I write, “Although we are all unwitting members of this invisible labor pool, some are more at risk than others.” I thought often about my privilege as I was working on the essay. And I kept returning to the thought that, even with my privilege, my mom and I were in serious trouble. I decided to use my platform as a public health professor to draw attention to the caregiving challenge facing millions of Americans.

Did you make any connections between your personal experience and your professional expertise on global health? Did you perhaps notice any similarities between the US healthcare system and healthcare operations in under-resourced settings?

I am in the middle of teaching the Global Mental Health class right now, and one of the things that we talk about—paraphrased from the Lancet Commission on Global Mental Health and Sustainable Development—is that when it comes to mental health, every country is a developing country. Am I going too far out on a limb to say that when it comes to long-term care, we are a developing country? We are relying on fantasy extended family networks and women working in the home. This does not match the reality of most American families, and hasn’t for decades.

If readers heed one message from your story, what do you hope that is?

You are not alone. It should not and does not need to be this way. If you can, buy a long-term-care insurance policy. Find a way to protect your life savings.

I am generally an optimist about most things, but I have come out of this experience feeling cynical, even bitter about the health care situation in the US. We are always talking about how to fix the system we have when what we probably need to do is throw it out and start anew. I know that sounds naive, even glib. But I’m okay with that. I want a health system that actually provides care. Other countries seem to take that responsibility seriously—there are abundant examples. All are imperfect, but they offer humane, pragmatic examples of a way forward.