Tang Yan Receives ACOSA Doctoral Student Award for Work with Linguistically Diverse Families

Student joins forces with community advocates to promote language justice and equity for culturally diverse families

BUSSW doctoral candidate Catalina Tang Yan has received the Association for Community Organization and Social Action’s (ACOSA) 2020 Doctoral Student Award. This award honors PhD students who demonstrate outstanding scholarly potential in community and/or organizational practice through their dissertation, scholarly contributions, and substantial research dissemination. Tang Yan’s dissertation research focuses on interrogating power and interlocking systems of oppression within Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) collaborations to achieve economic, racial, language, and social justice. She expects to complete her doctorate degree in 2022.

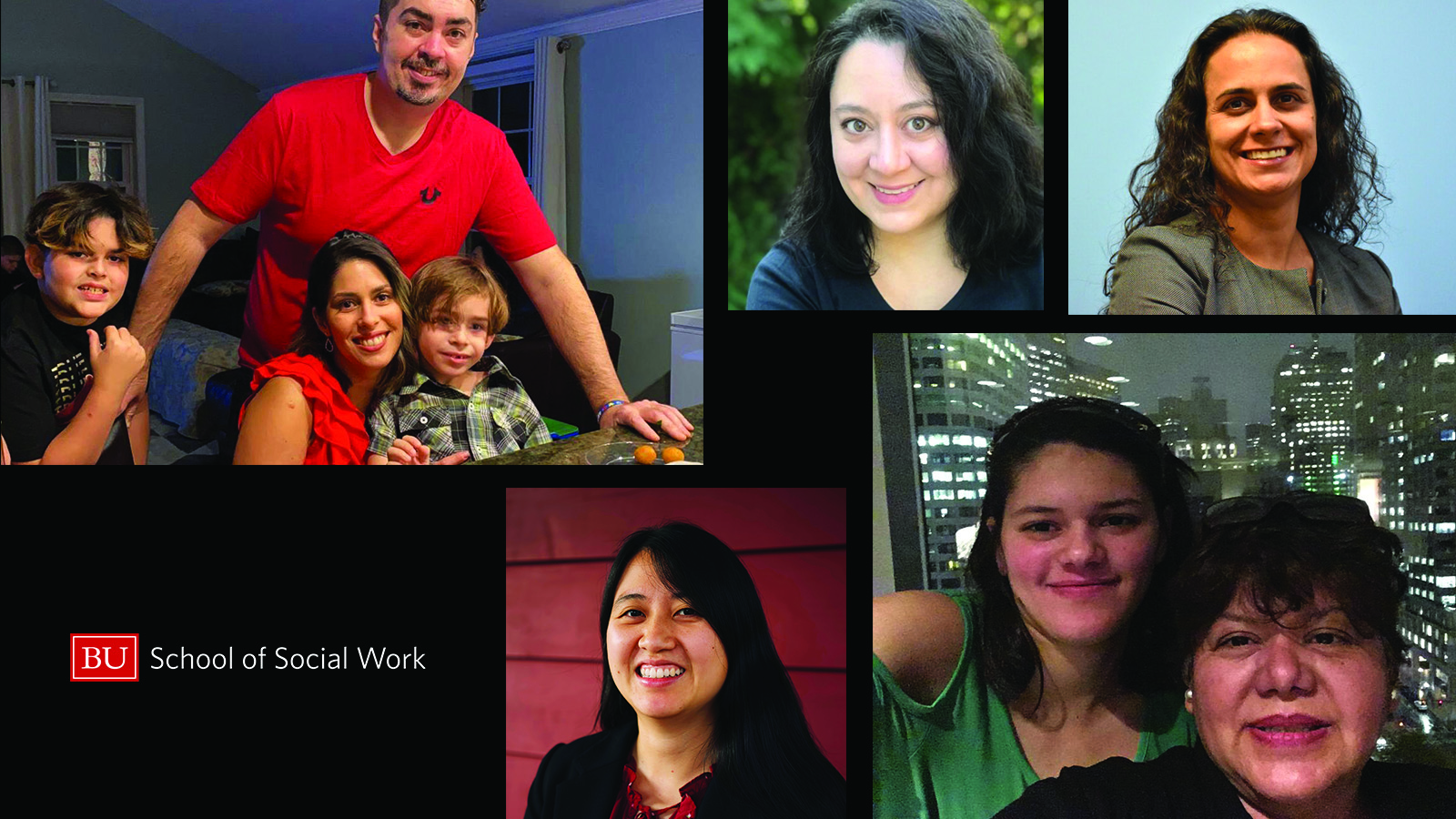

“While I’m incredibly grateful for the support of my mentors who nominated me for this award, Dr. Linda Sprague Martinez and Dr. Melvin Delgado, I’d like to emphasize that this award is the result of a collective effort and belongs to my community collaborators, colleagues, and members of the Community Advisory Team (CAT), especially Angélica Bachour, Consuelo J. Pérez and Loreto P. Ansaldo,” says Tang Yan.

“While I’m incredibly grateful for the support of my mentors who nominated me for this award, Dr. Linda Sprague Martinez and Dr. Melvin Delgado, I’d like to emphasize that this award is the result of a collective effort and belongs to my community collaborators, colleagues, and members of the Community Advisory Team (CAT), especially Angélica Bachour, Consuelo J. Pérez and Loreto P. Ansaldo,” says Tang Yan.

In their project “Partnering with Families with Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Families to Promote Language Justice and Equity in Education Settings” – funded with the support of BU Initiative On Cities’ Urban Research Award – Tang Yan and members of CAT partnered with a coalition of culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD) mothers, advocates, community interpreters/translators and educators to explore the support and barriers immigrant mothers of children with special needs experience when advocating for their children’s education. Together, their team conducted multilingual focus groups and “know your rights” workshops with 21 of these mothers, all speakers of one of the three most common non-English language groups represented in Massachusetts.

“These findings validate what parents and caregivers already know and experience,” states Consuelo J. Pérez, an artist, parent advocate, community interpreter, and mother of a child with special needs. “Institutions don’t recognize the voices of parents, and it is important that researchers center the leadership and voices of parents to push institutions, including schools and universities, to be accountable to immigrant families and caregivers.”

Loreto P. Ansaldo – community interpreter, translator and a former classroom teacher – agrees. “The leaders already exist, but we haven’t supported the work that will lead us to solutions.”

Diana Santiago, Esq., a senior attorney focusing on special education matters at Massachusetts Advocates for Children, emphasizes the role of participatory research in strengthening advocacy efforts. “I think that some of the ideas from the group can help shape and inform our work in those areas in terms of including parent voice and getting a better understanding of where families are coming from to inform the advocacy.”

Angélica Bachour, immigrant mother of two children with special needs and parent advocate, offers a recommendation for all institutions working with CLD families: “Always have the parents leading,” says Bachour. “Parents have the power. The important thing is to listen to them.”