George Fox, STH ’34

O beautiful for heroes proved in liberating strife,

Who more than self their country loved,

And mercy more than life!

America! America! May God thy gold refine

Till all success be nobleness,

And ev’ry gain divine!

When Katharine Lee Bates penned these lines in 1913, she no doubt had in mind the sacrifices made by the thousands who had already offered their lives for the sake of their country. George L. Fox was only thirteen years old when the song was written. Nevertheless, Bate’s poem would prove to be an apt epithet to Fox’ memory. Fox sacrificed his own life for the sake of another, giving up his life vest on a sinking ship to another sailor during the Second World War. The courage of Fox and his fellow chaplains embodied the highest calling of military chaplains—to love mercy more than life.

Born in Lewistown, Pennsylvania on March 15, 1900, Fox had a strong draw to military service. When he was only 17, he left school to join the military. Lying about his age, Fox convinced the ambulance corps that he was 18. After undergoing basic training, his unit was sent to the trenches in France during the First World War. There, Fox committed a number of acts of bravery, earning a Silver Star, the Purple Heart, and the French Croix de Guerre. Returning from the “War to End All Wars,” Fox began to build a life. He married, started working as an itinerate preacher, and began moving between educational institutions. After a brief stint at the Moody Institute, he attended Illinois Wesleyan University (AB 1931) and later Boston University School of Theology where he earned an STB in 1934. That same year, he was ordained as a Methodist minister. As Fox began setting up a comfortable life in New England, working as a minister and a chaplain in Vermont, Germany was in the process of rearmament and Japan began expanding their empire in Asia and the pacific. It was only a matter of time before Fox would find himself back in the military. In early 1942, Fox joined the Army Chaplain Service and his son, Wyatt, enlisted in the Marine Corps. In that same year, George went to Harvard’s Chaplain School.[1]

At Harvard, Fox met a number of men training for ministry to military personnel from across religious and denominational lines. One of Fox’s classmates was Alexander Goode—a Jewish rabbi from Brooklyn, New York. Goode was an intellectually gifted man, graduating from the University of Cincinnati (A.B.), Hebrew Union College (B.H.), and the Johns Hopkins University (Ph.D., 1940). Goode attempted to become a Navy chaplain as early as January 1941, but was rejected. After Pearl Harbor, he reapplied for the job, and the military accepted his application.[2] Clark V. Poling was another student. Poling grew up in a multidenominational atmosphere. His father was an evangelical preacher who later became a Baptist. Growing up, Poling attended a Quaker high school. After graduating from Rutgers University, he felt the call to ordained ministry and entered Yale Divinity School. After receiving his B.D., the Reformed Church in America ordained Poling as a minister.[3] Fox, Goode, and Poling were all married with children by the time they entered the Chaplain’s School. Their classmate John P. Washington was a Roman Catholic priest. He grew up in Newark, New Jersey and quickly excelled through the Catholic School system. Washington attended Seton Hall in South Orange, New Jersey, which combined high school and his first few years of college in preparation for the priesthood. He then entered the Immaculate Conception Seminary in Darlington, New Jersey. After receiving his minor orders, Washington worked as a priest throughout New Jersey. Shortly after Pearl Harbor, he received an appointment as an Army Chaplain.[4]

All four of these men boarded the USAT Dorchester in late January of 1943. The ship steamed out of Boston Harbor, turning into the icy waters of the North Atlantic, heading toward Greenland. The ship itself was not originally intended for military use. The Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company built the vessel for the Merchant and Miners Transport Company in 1926. In those days, it was actually a luxury liner. It carried passengers along the East Coast, moving from Boson to Miami, making stops in Philadelphia, Baltimore, Norfolk, Savannah, and Jacksonville. In peace times, passengers were able to stay in comfortable rooms with electric fans and telephones. Both morning and into the late hours of the night, the ships crew offered cold ice cream, music for dancing, and deck games. The ship offered New Englanders a chance to escape the miserable cold of Northern Winters, and Southerners a chance to leave behind the oppressive heat and humidity of summer. Yet across America, the declaration of war brought the amusements of peacetime to an end. In February of 1942, the Atlantic, Gulf, and West Indies SS Company fitted the Dorchester with several guns and installed new bunks that increased the ship’s capacity by nearly a factor of three. The Navy placed several guards on board to man the guns. In January of 1943, the four chaplains were joined on the ship by 898 additional people.[5]

The captain of the Dorchester, Hans J. Danielsen, knew that the way to Greenland was dangerous. The German Navy went to great lengths to prevent soldiers and provisions from crossing the Atlantic. German submarines or U-Boats torpedoed Allied vessels throughout the Atlantic and also set up a web of mines. Danielsen was well aware of this danger and issued an order for all troops to sleep in their clothes and to wear their life vest. Many troops did not follow this order. The heat from the engines made wearing the vests very uncomfortable. Danielsen was no doubt extra cautious when the Coast Guard reported a U-Boat on their sonar. Not taking any chances, Danielsen stationed extra lookouts, and doggedly pressed on into the open ocean. His hope was that by midnight, the ship would enter a field of icebergs, providing some cover for the ship. There was no such luck. 150 miles away from Cape Farewell, shortly after midnight, a German U-Boat officer spotted the Dorchester.[6]

Under the command of Karl-Jürg Wächter, U-223 was sailing on its first patrol. It left the German city of Kiel on January 12, 1943, and sailed north along the coast of Norway before turning into the Atlantic and moving toward Greenland. After noticing the allied convey, Wächter ordered the ship into attack mode. Cutting the diesel engines, the U-Boat switched on batter power and silently submerged into the cold, dark water. Setting their sights on the Dorchester along with two other ships in the convoy, Wächter ordered the firing of five torpedoes. At least one and perhaps two torpedoes made contact with the Dorchester’s starboard hull. A muffled explosion followed by a blast reverberated through the ship and the lights went out. Many men were caught below deck, unable to see as the ship began listing to the starboard. Getting his bearings, Danielsen attempted to blow the distress whistle, but the steam gave out. He ordered the ship to be abandoned.[7]

Terror and pandemonium ripped through the soldiers. Army Air Force member Walter A. Boeckholt remembered,

I was thrown against the ceiling and then landed on the floor. By the time I was recovering my senses, the ship was already tilting. I grabbed for the door, which hadn’t jammed as of yet, and walked out on deck, realizing I didn’t have my life preserver, I went back into the room to get it. As I returned to the deck, they all seemed to be yelling, crying, and trying to get to their lifeboats. Most of the lifeboats were frozen solid or broken in the process of trying to get them loose.[8]

Many soldiers had forgotten their life preservers in the chaos of the moment. In the midst of the commotion, the four chaplains—George Fox, Alexander Goode, Clark Poling, and John Washington, found their way on deck, attempting to calm the terrified soldiers and direct them to safety. The four chaplains found a box of life preservers and began handing them out to men as they passed by. As they worked among the crowed, they offered prayers and words of courage. Finally, there were no more life vests in the box, and each chaplain gave up his own life vest in the hope that another man might live. Standing on a sinking ship, facing a certain death, the four men then linked arms and began to pray.[9]

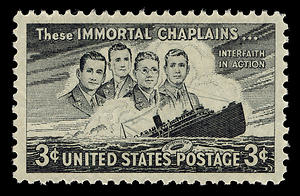

In the early morning hours of February 3, 1943, amid the pandemonium and terror of a sinking ship, four men from different religious traditions faced eternity together. They each sacrificed their own lives for the hope that others might live. A first century rabbi once said, “There is no greater love than this, to lay down your life for one’s friends.” The “immortal chaplains” of the USAT Dorchester demonstrated this great love when they gave everything they could give and prayerfully faced eternity. For their bravery, Lieutenant General Brehon B. Somerville awarded their next of kin the Distinguished Service Cross and the Purple Heart posthumously on December 14, 1944. Again, in 1961, the United States Congress authorized a one-time Special Medal for Heroism that president Eisenhower awarded these four men.[10]

S.J. Lloyd

[1] “George L. Fox,” The Four Chaplains Memorial Foundation http://www.fourchaplains.org/fox.html.

[2] Ibid., http://www.fourchaplains.org/goode.html.

[3] Ibid., http://www.fourchaplains.org/poling.html.

[4] Ibid., http://www.fourchaplains.org/washington.html.

[5] Stanley Brewer, “S.S. Dorchester” Great Ships http://www.greatships.net/dorchester.html

[6] Michael G. Walling, Bloodstained Sea (Cutter Publishing, 2009), 113.

[7] The account here is largely derived from Walling, 113-116, and “The Story,” http://www.fourchaplains.org/story.html. While most details agree, the account on uboat.net argues that the Dorchester was able to sound all six blasts of the whistle. The discrepancy in time comes from the fact that U-223 operated on Berlin time, while the Dorcester had its clocks set to Greenland time. Uboat.net also has details of the rescue attempt. “Dorchester,” http://uboat.net/allies/merchants/ships/2616.html. For more on the fascinating character of Wächter, see http://uboat.net/men/commanders/1311.html. For information on the sinking of U-223, see http://uboat.net/boats/u223.htm.

[8] Boeckholt in Walling, 115-116.

[9] “The Story,” The Four Chaplains Memorial Foundation http://www.fourchaplains.org/story.html.

[10] “The Story,” The Four Chaplains Memorial Foundation http://www.fourchaplains.org/story.html.