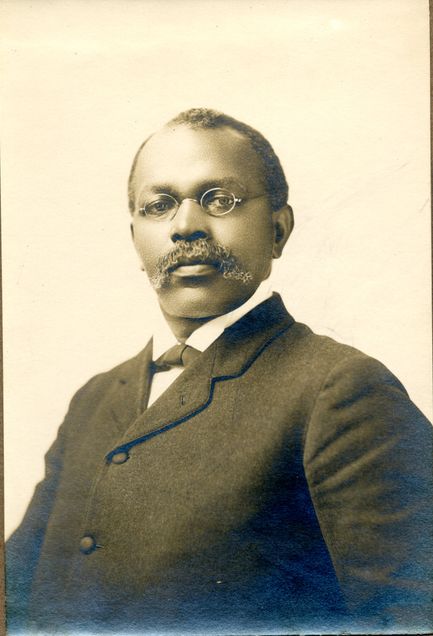

John Wesley Edward Bowen (1885)

J.W.E. (John Wesley Edward) Bowen lived during a time in which the legal and social position of African-Americans in the United States, and especially, in the South was in rapid flux. He was born into slavery in New Orleans, but at the tender age of three, his father purchased the family’s freedom. When Bowen turned six, the state of Louisiana seceded from the Union. For New Orleans succession was short-lived. Federal troops occupied the city on April 25, 1862, and shortly thereafter, Bowen’s father joined the Union in the fight against slavery. By Bowen’s thirteenth birthday, the war had just ended and the death knells for slavery rang out as the United States ratified the 14th Amendment.[1]

J.W.E. (John Wesley Edward) Bowen lived during a time in which the legal and social position of African-Americans in the United States, and especially, in the South was in rapid flux. He was born into slavery in New Orleans, but at the tender age of three, his father purchased the family’s freedom. When Bowen turned six, the state of Louisiana seceded from the Union. For New Orleans succession was short-lived. Federal troops occupied the city on April 25, 1862, and shortly thereafter, Bowen’s father joined the Union in the fight against slavery. By Bowen’s thirteenth birthday, the war had just ended and the death knells for slavery rang out as the United States ratified the 14th Amendment.[1]

After the war, Bowen attended the Union Normal School in New Orleans, where he proved to be a very promising student. After graduating in 1878, he attended New Orleans University—a school founded by Methodists for the education of former slaves. Again, he excelled, mastering Latin, Greek, and mathematics to such an extent that he was hired to teach these subjects at Tennessee College. In his mid-twenties, Bowen travelled north to Boston University, where he would leave his mark on an institution that sought to train prophetic voices for our world. Bowen received a Bachelors of Divinity in 1885. The following year he married Ariel Serena Hedges, and began a doctoral degree in historical theology, which he completed in 1887. He was to be the first African-American to earn the Ph.D. degree at Boston University. Bowen went on to teach briefly at Morgan College in Baltimore and Howard University in Washington before settling into a post at Gammon Theological Seminary, where he taught from 1893 until he retired as an emeritus in 1932.[2]

From slavery in Louisiana to the height of academic excellence, Bowen no doubt fulfilled his father’s dreams for a new America. Yet not all former slaves had such opportunities. After the passage of the 14th amendment, various factions began vying for power in the South. W.E.B. Du Bois wrote, “The South is not ‘solid’; it is a land in the ferment of social change, wherein forces of all kinds are fighting for supremacy.” While there was a party that sought the economic and political empowerment of African-Americans, others wished to maintain power structures similar to those of slavery. Du Bois described the situation as follows: “the ignorant Southerner hates the Negro, the workingmen fear his competition, the money makers wish to use him as a laborer, some of the educated see a menace in his upward development, while others—usually the sons of the masters—wish to help him rise.”[3] Blacks were kept from the polls by a myriad of unfair and often humiliating legislation, such as poll taxes, grandfather clauses, and literacy tests. Likewise, segregation became the law of the land. The so-called “Jim Crow” laws segregated schools, trains, water fountains, and rest rooms. All of this was legal according to the United States Supreme Court’s decision in the case of Plessey v. Ferguson. In cases where African-Americans were suspected of crimes or even of upsetting the social order, white mobs enacted the cruel vigilantly punishment of lynching. While slavery had ended, African-Americans remained second-class citizens.

Bowen was among a generation of African-American intellectuals who sought to achieve a more just society. He was certainly no stranger to the brutality of white American society. In 1906, the same year that Bowen became President of Gammon, racial tension was palpable in Atlanta. There was growing prosperity among an African-American middle class, and this was particularly threatening to the white establishment. White political candidates played to the fears of the white community, suggesting that black disenfranchisement would be necessary to avoid competition for jobs. Likewise, a large class of poor blacks also proved threatening to white society. Poor black men were depicted as drunk, lascivious, and violent. On September 22, the tensions boiled over when local newspapers reported four (unsubstantiated) assaults on white women. White men formed a mob in downtown Atlanta. From the early evening into the night, the mob began to attack black people and black-owned businesses. At least three African-American men were beaten to death.[4] J.W.E. Bowen was among those who were brutalized. During the riots, Bowen offered Gammon as a place of shelter. He was beaten and arrested.[5]

This was the world that African-American intellectuals sought to address. While there was significant diversity in their positions, one can identify three main streams of thought. One of the older solutions to race relations in the United States was one of sending black Americans back to Africa. Beginning at the turn of the 19th century, an unlikely alliance developed between Southern slave owners concerned with a growing free black population and Northern philanthropists who sought to rectify the evils of slavery. They formed colonization societies, and the small African nation of Liberia was the result.[6] The “back to Africa” idea was never popular among African-Americans. Nevertheless, for some, such as Marcus Garvey, the option of leaving a world of white racism proved very attractive.

Booker T. Washington, on the other hand, told African-Americans to “cast down your bucket where you are.” In the 1895 Atlanta Compromise, Washington argued that manual and technical labor would lead to the racial uplift of Southern African-Americans. He said, “No race can prosper till it learns that there is as much dignity in tilling a field as in writing a poem. It is at the bottom of life we must begin.”[7] W.E.B. Du Bois vehemently opposed to this position, calling it retrograde and submissive. Rather than gaining respect through manual labor, Du Bois argued that African-Americans needed to demand the right to vote, civic equality, and educational opportunities for young people. As he wrote, “Negroes must insist continually, in season and out of season, that voting is necessary to modern manhood, that color discrimination is barbarism, and that black boys need education as well as white boys.”[8]

In his own writings, Bowen was in conversation with all of these positions. In 1895, at the age of 40, Bowen served as secretary of a three-day conference on Africa at the Cotton States Exposition held in Atlanta. Bowen was an active promoter of African missions. He was Secretary of the Stewart Missionary Foundation for Africa at Gammon, and he edited the Stewart Missionary Magazine. In a speech given at the “Africa and the American Negro Conference,” Bowen talked about the degradation of slavery. He argued that the supposed advancement of learning the English language or the Christian religion did not excuse the ethical abuses and crimes of slavery. Rather, he argued, it was only when slavery ended that African-Americans have gained the tools for advancement—education (particularly in the morals of the Christian religion), land ownership, and civil rights. In concluding his speech on “The Comparative Status of the Negro at the Close of the War and To-day,” Bowen said

Before the war the Negro was a dumb-driven and a dumb-used cattle for work and for breeding. Shame, the virtue that Eve brought out of the Garden with her, that belongs alike to heathen and to Christian, was mocked, insulted and trampled under merciless hoofs. The women were the tools for lechery and leechery. The whole head of the race was sick and the heart was faint, bruises and putrifying sores covered the body of the race. Today, in education, in morals, in spiritual power, the Negro is far superior. He marries according to law, rears his family in a home of culture and morality, and reaches up with divine aspirations to the ideal perfections of human nature. The women are women. And while it is true that as a mass the race has not yet attained unto all perfection, yet they press with vigor toward the mark and are far removed from that dark age. They are purer, their preachers have improved and are still improving in all the elements of moral power. THE MORN COMETH.[9]

Also at the Cotton States Exposition, on “Negro Day,” he delivered a speech entitled “An Appeal to the King.” Setting himself apart from Marcus Garvey and the “back to Africa movement,” he recognized the United States, and indeed the American South, as the birthplace and true home of African-Americans. In claiming this, Bowen argued that African-Americans should not have to leave the South, nor should the South be regarded as a “white man’s” world. Instead, he argued the average African-Americans of his day

Loves the land of his nativity and is ready, as of yore, to pour out his heart’s best blood for the institutions of that land. The sad and sweet memory of his historic sorrows saturate this atmosphere and every foot of ground in Southern soil is made holy because it embalms the sacred dust of his faithful sires.[10]

In taking this stand, Bowen makes a claim for the African-American place in the Southern milieu. The South is the land where African-Americans were enslaved; nevertheless, blacks toiled to build the South, raised families there, and were laid to rest on that land. The land belonged to them and they belonged to the land as much as any white person.

After establishing the connection between African-Americans and the American South, Bowen went on to discuss the pressing racial question. He discussed it not so much as a problem specific to the South, but rather as one particular manifestation of a much larger issue. “Our ears have become familiar with the so-called race problem, which has been popularly interpreted to mean the Negro race problem. A truer and larger conception of the subject would speak of the human race problem.”[11] Bowen then continued, citing that Germany had a problem with socialists, France with communists, California with the Chinese, the Northeastern United States with the Irish and Italians, the Midwest with the Scandinavians, and the South struggled with the question of integration of African-Americans. For Bowen, all of these “problems” stemmed from a lack of justice. Bowen understood equality to be at the basis of New Testament teachings. It was not, however, an equality that blotted out individual differences, but rather it leveled the social and national playing field, allowing each person, regardless of race, to live into his or her capacities fully. As he wrote,

The largest struggle of human society is to attain this concrete reality of civil justice. Under it, each will produce according to his ability for the good of mankind, and that will not cast into the stereotyped mold of racial captivity, but will be complex in its essentials and divinely human in its cast.[12]

Bowen continued parsing out the notion of equality and diversity, arguing that while there was not perfect equality among human beings, every individual person contained the essence of humanity and the imprint of the creator. In this way, he placed himself in the Judeo-Christian and Enlightenment understanding of humanity, espoused by the “founding fathers” of the United States. He wrote,

There is no such thing as perfect equality of individuals or races. This is a figment clung to by minds that are woefully deficient in rudimentary training or are still wrapped in the swaddling bands of medieval infancy. The true or native equality of men as stated by the great Jefferson in the fundamental character of the republic, and as rationally and biblically interpreted in biology, philosophy, reason, Scripture, and common sense, is that all men are natively and equally endowed with the essentials of humanity and divinity. And because of this, all should be permitted to develop their endowments for the good society within the limits of unprejudiced legislation.[13]

In a way, Bowen criticized Americans for not being American enough. The basic idea of the American experiment is that while every individual is unique, all people have are alike in dignity and deserve to be treated as such by the law. It was hypocrisy that many white individuals claimed an American identity while deliberately seeking to disenfranchise African-Americans.

Bowen develops the idea of equality further using a leitmotif with the idea of a yard. He said, “The Negro has learned that three feet make a yard in mathematics, and he believes that they make a yard in politics, economics, and ethics; in Europe, Asia, and Africa; among whites and among blacks.”[14] In the same way that a yard is always a yard, justice is always justice, and it must be distributed equitably to all people. African-Americans were made to feel that because of the color of their skin they only deserved jobs at the bottom rung of the American economic order. Bowen wrote, “With regard to the Negro’s place in American life, it was formerly stated that he was only fit for servitude; that the best part of him was his faithful muscle; that even today and forever more he must remain a serf or a hewer of wood and a drawer of water to the vast revolving machinery of civilization; he must be the ignorant workman and the unassimilated pariah of American society.”[15] Yet while African-Americans were constantly made to feel inferior, they learned that a yard is a yard, and that justice is justice, and many began to demand what was due to them. Bowen is very careful not to say that African-Americans should be exempt from working or manual labor. Indeed, he may have been anticipating some of the criticism of racists who called blacks “lazy and shiftless.” Bowen celebrated the labor of African-Americans, while seeking to upset the assumption that blacks were only meant for medial work. Bowen wanted African-Americans to have to opportunity to guide, direct, and reformulate the American economic machine. If a yard is a yard, then African-Americans and whites both needed to work together for the future of the country. Note how he presents a people eager to work at all levels of society:

When it is asserted that he must be a worker, all sensible Negroes answer yea and amen! A worker in clay wrenching from nature her hidden stores; a worker in wood, iron, brass, steel, and glass turning the world into an habitation fit for the Gods; a worker in the subtle elements of nature in obedience to the command to subdue and conquer it; a worker in the realm of mind contributing to the thought-products of mankind, thereby vindicating for himself a birthright to the citizenship of the republic of thought; a statesman in church and in state; a publicist and a political economist; in short he must be a man among men, not so much a Black man but a MAN though black. And for all the attainment of all the possibilities of his rich, unexplored African nature of docility and tractability of enthusiasm and perseverance, which his burning African fervor, there must be measured to him as well as to the white man three feet to make a yard.[16]

For Bowen, like du Bois, the main institution that will allow for a shift in the power dynamic is education. He paints an image of a statue in his speech, discussing the “New Negro.” Bowen talks about a statue of an African American man, standing with his shackles broken. The man is of a strong physic and fixes his gaze on the chains, and furrows his brow. “What is he doing?” Bowen asks, “He is thinking!” For Bowen, the power to be educated, and the power to think critically about one’s situation would give that person the ability to find solutions to their greatest problems. Bowen thought that education would prove to be the way forward for African-Americans in the south, and humanity more generally. He wrote, “…by the power of thought, he will think off those chains and have both hands free to help you build this country and make a grand destiny of himself.”[17]

Bowen died in 1932. He did not know Rosa Park, he did not walk in the million-man march, and he did he witness the voting rights act of 1965. From today’s standpoint, the civil rights era took place in the 1950s and the 1960s. Yet the conversation about justice, equality, and civil rights was much older. Boston University served as a platform for that conversation; indeed, it will be a credit to this institution for many years to come. Bowen was one of the first in long line of African-American intellectuals who walked through Boston University with an eye on future justice. J.W.E. Bowen, Howard Thurman, and Martin Luther King, Jr. to name only a few certainly lived up to the highest call of prophetic ministry. When Americans made an idol of race, these men called us away from false worship. When America privileged some at the expense of others, they called for justice. Bowen’s voice, though historically constrained, continues to find resonance in the ears of those who struggle to make a more equitable society.

S.J. Lloyd

[1] Anneke Helen Stasson, “Bowen, John Wesley Edward (1855-1933),” Boston University History of Missiology Website. http://www.bu.edu/missiology/missionary-biography/a-c/bowen-john-wesley-edward-1855-1933/

[2] Ibid.

[3] W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (Rockville, MD: ARC Manor, 2008), 45.

[4] Gregory Mixon and Clifford Kuhn, “Atlanta Race Riot of 1906,” New Georgia Encyclopedia. 2014. http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/atlanta-race-riot-1906.

[5] Stasson.

[6] Lamin Sanneh, Abolitionists Abroad: American Blacks and the Making of Modern West Africa (Harvard University Press, 1999), 183-192.

[7] Booker T. Washington, “1895 Atlanta Compromise Speech,” http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/39/.

[8] Du Bois, 44.

[9] J.W.E. Bowen, ““The Comparative Status of the Negro at the Close of the War and To-day,” Africa and the American Negro: Addresses and Processdings of the Congress on Africa, ed. J.W.E. Bowen (Atlanta: Gammon Theological Seminary, 1896), 173.

[10] J.W.E. Bowen, “An Appeal to the King,” The New Negro: Readings on Race, Representation, and African American Culture, 1892-1938, eds. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Gene Andrew Jarrett (Princeton University Press, 2007), 27.

[11] Ibid., 27.

[12] Ibid., 28.

[13] Ibid., 28.

[14] Ibid., 28.

[15] Ibid., 29.

[16] Ibid., 29.

[17] Ibid., 32.