Forgotten African American Stories, Told in Comic Books

To Joel Gill (CFA’04), it’s not black history, it’s American history

Comics artist and educator Joel Gill (CFA’04) with an oil painting of his two daughters, done as part of his BU thesis, that now hangs in his New Hampshire living room.

Home to about 50 mixed-race descendants of a freed slave, Malaga Island off Maine’s coast seemed an oasis of racial harmony in 1912. But then the state, lobbied by reformers who saw residents living in poverty—and perhaps tempted by a land grab too good to pass up—evicted the islanders. The majority who complied were the lucky ones. Those who held out were netted in the nascent eugenics fervor: declared feebleminded, they were confined and in some cases castrated.

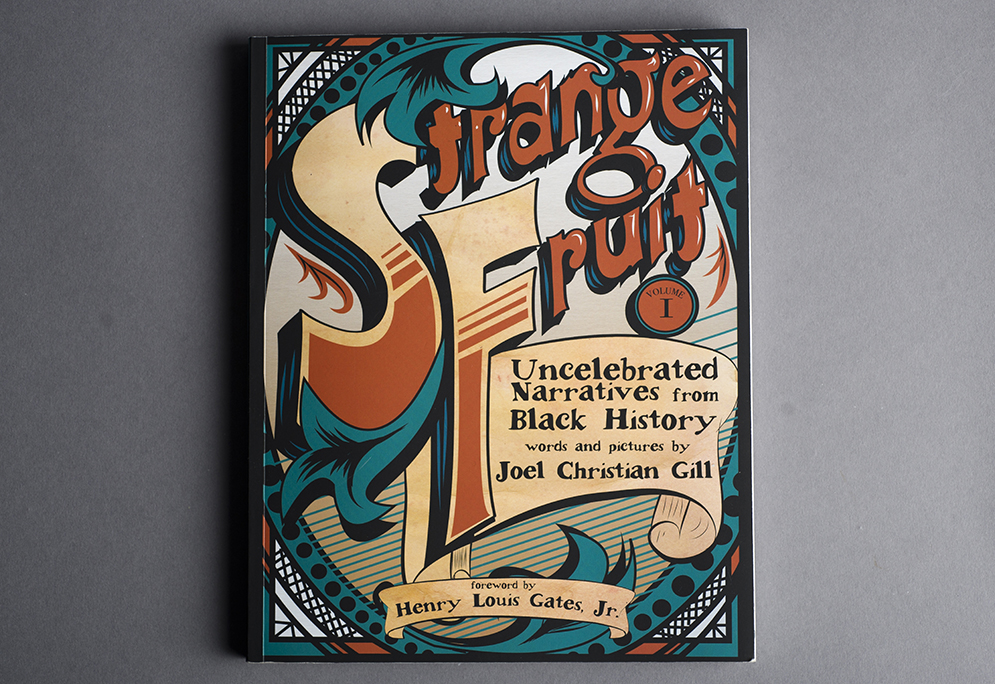

Despite an official apology from Maine’s governor in 2010 and a radio documentary about the case, Malaga’s story might have remained little known but for Joel Christian Gill (CFA’04). His graphic anthology Strange Fruit, published last year by Colorado-based Fulcrum, uses comics to tell the stories of African Americans whose contributions and sufferings occupy obscure fringes in the country’s historical memory.

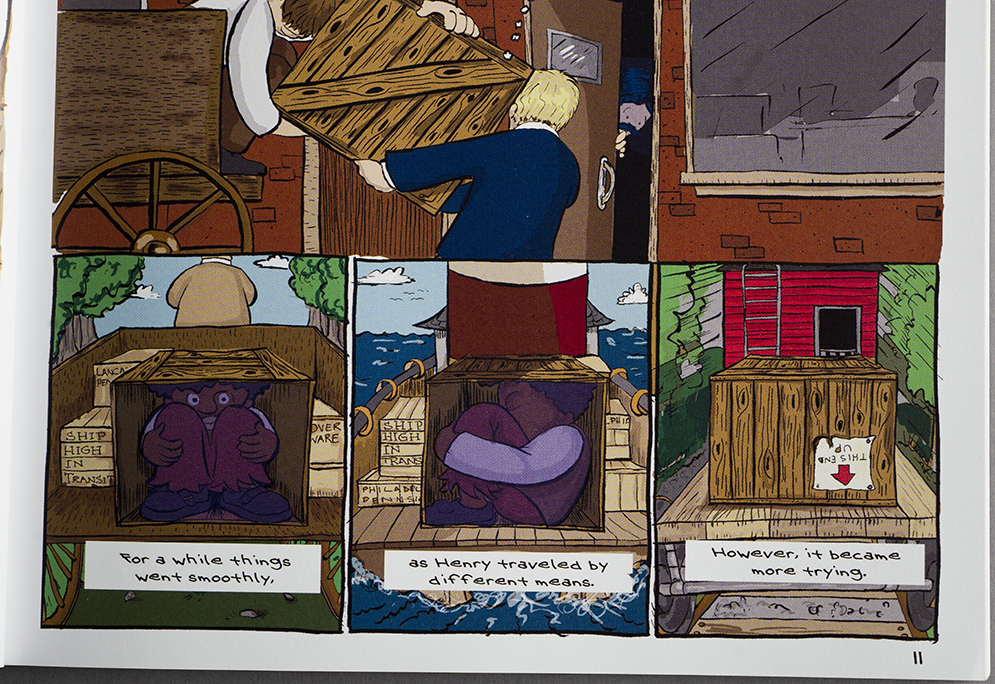

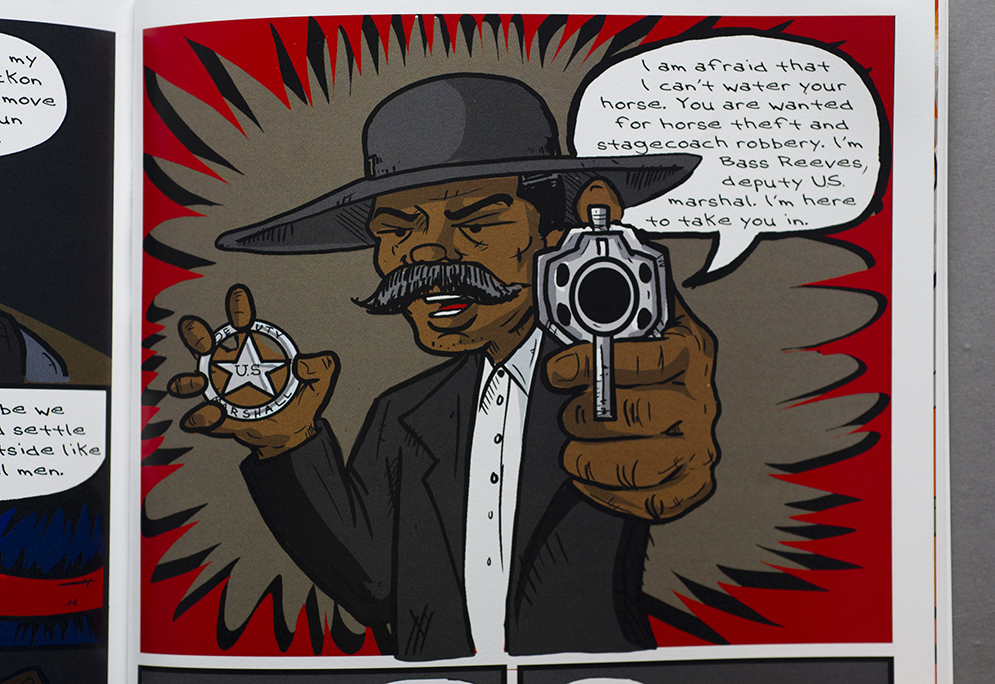

Besides Malaga, the nine tales in Strange Fruit include those of Bass Reeves, a black lawman in the Old West so adroit at nabbing bad guys that he may have been an inspiration for the Lone Ranger; Richard Potter, America’s first stage magician, who became rich passing as a white man, revealing only on his deathbed in 1835 that his mother had been black; and Henry “Box” Brown, a Virginia slave who escaped to freedom in 1849—by mailing himself to Philadelphia in a cramped crate, emerging after a 27-hour ordeal by wagon ride.

“This is not just the history of black people. This is our history. It’s American history,” says Gill, associate dean of student affairs at the New Hampshire Institute of Art, who is at work on a follow-up volume. He has already published a stand-alone graphic biography of Reeves, Tales of the Talented Tenth. (The absence of women’s stories in Strange Fruit, he confessed on the PBS show Basic Black, was an oversight owing to “male privilege,” and will be rectified in the next volume.)

Reviews for Strange Fruit were positive. The New York Times recommended it as a gift last Christmas, commending its “thoughtful reflections” and “pointed text.…At a moment when racial inequities have ignited this nation, Mr. Gill offers direction for the road ahead from the road behind.” School of Education lecturer Laura Jiménez, who researches how readers engage with graphic novels, says Strange Fruit should be used in social studies and history classes for its premise “that we, as Americans, can look beyond a single set of heroes and see a rich tradition of greatness in any culture. This is a pretty radical notion, and I think Gill delivers with this book.”

Jiménez also admires Gill’s artistry, his “use of full, rich color in his work. He uses a palette that underscores the sort of old-timey history he is writing about.” In telling the story of Major Taylor, a fin de siècle cyclist who was America’s first black sports champion, Gill varies the skin tone in his pictures of Taylor’s family, even though they all were related. “You’d be surprised at how often illustrators color characters of similar races…the same color,” says Jiménez. “As if there is a single color grade for any group of people.”

Gill’s drawings reflect his quest for authenticity; his Bass Reeves is wiry, he told NBC News, because a Wild West marshal spent hours in the saddle and didn’t have much time to eat. Yet the artist’s imaginative use of symbolism came to bear as he sought an alternative in his books’ text bubbles to the N-word, which he thinks conjures different things for different people. Instead, he drew a picture of a minstrel in blackface to convey the racist slur. That a picture, reflecting a well-known prejudice, can sub for a vile word shows comics’ power, Gill says; they allow him to “imbed in these symbols that sort of hieroglyphic history that you can’t do with…a regular book.”

Click through a gallery of Joel Gill’s work above.

Forsaking painting for comics

Here are some little-known facts that this chronicler of little-known facts shares about himself: his father died when he was young, leaving Gill to be raised by a single mom in Virginia, which makes him bristle at one reviewer’s suggestion that omitting women from his book is misogynistic. (“It took me until I was probably a teenager to realize that people didn’t think women could do things. A woman taught me how to fight. Everything I learned in life, I learned from a woman.”)

He owns two dogs—and some cats, because his family likes them, though he’s a cat hater: “They are horrible, horrible people.” He grew up loving comics; today, his studio in a converted garage at his rural New Hampshire home is filled with boxes of old X-Men, Preacher, and other superhero tales.

Gill studied graphic design as an undergraduate at Roanoke College, but fell in love with painting after taking a class. He came to BU to pursue an MFA in painting, but as the father of four young children, he recalls, he was so broke that he faced an eviction proceeding the same day as his thesis presentation. The University rescued him with a scholarship that covered the rent.

The most memorable comment on his work at BU, he says, was a single sentence: “You had poetry here, and you f—ed it up.” John Walker’s critique of a painting of some now-forgotten subject stayed with his student, and not because it was offensive. The CFA professor of art “was absolutely right,” Gill says, and instilled in his pupil a firm work ethic that keeps him refining his artwork to this day.

An African American who’d felt perfectly safe in his hometown and had never experienced racism in Boston, Gill says he was startled when someone warned him to avoid certain racist neighborhoods in Beantown. Pondering this after graduation, he painted a series of self-portraits inspired by lynching photos he’d seen. The paintings depicted him with a noose around his neck, but holding the frayed end of the rope, symbolizing his freedom from the fear that plagued his ancestors while nodding to lingering racial prejudice. Cued by Billie Holiday’s lynching-protest song Strange Fruit, Gill titled his paintings Strange Fruit Harvested: He Cut the Rope. A friendly observer confided, “It seems like your paintings are trying to tell stories, and they’re failing.”

That got him to thinking about his first love, comics, and how their blend of pictures and words might fill that storytelling gap. He admired works like the Pulitzer-winning graphic novel Maus, wherein cartoonist Art Spiegelman recounts his father’s surviving the Holocaust, drawing Jews as mice and Nazis as cats. “I think comics can reach most people in a way” other media cannot, Gill says. “There was no explanation…like ‘cats don’t treat mice very well’….We all know how that is, and we get the imagery.”

Switching from painting to comics required an artistic adjustment. Whereas a painter, knowing onlookers’ gaze will linger over a canvas, strives for perfection, Gill says, with comics “I can’t do that. Because as soon as you start looking at the amazing quality of the texture that I put on that man’s skin…then you’re immediately out of the story. It’s like switching from English to German. You’re now no longer reading the story. And so you have to sort of be subservient to the words.”

Before appearing in books, Gill’s comics were used by a foreign political campaign. In 2011, the opposition party in the Central American nation of Belize approached him. “I got an email from a guy, and it sounded like one of those Nigerian scam letters,” he says. “He was like, ‘We’re working on a political campaign, and we thought you’d be interested in working with us.’” His correspondent, a consultant, had stumbled across some of his work and was impressed. “I didn’t even know where Belize was at the time,” says Gill, who contributed some political cartoons that ended up on billboards and in a TV commercial.

The party using his cartoons lost. “I spent a lot of time making fun of the prime minister of Belize. I can’t actually go to Belize,” he says with a laugh.

By that point, he had already begun to research hidden moments and people from black history, fed by stories he’d hear at comics conventions. “There’s that whole idea that…history is written by the victors,” he says. “I think that history is not necessarily written by the victors. I think history is written by people who actually look for the truth.” The work ethic Walker taught him came in handy as he began Strange Fruit. He worked on the book off and on for five years, while completing his Bass Reeves bio took nine months of full-time work.

As media interest in Strange Fruit picked up, Gill created the comic #28 daysarenotenough, documenting his objection to the designation of February as Black History Month. (Aretha Franklin tweeted about his hashtag, he says.) “People don’t need months. They need to just be equally represented in history, across the board.”

If that happens, he told NBC, it could fulfill a dream: “I want lots of little white kids to read the story of Bass Reeves and say, ‘I want to grow up to be like Bass Reeves.’”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.