Remembering Howard Eichenbaum

Memorial to be held on campus Thursday

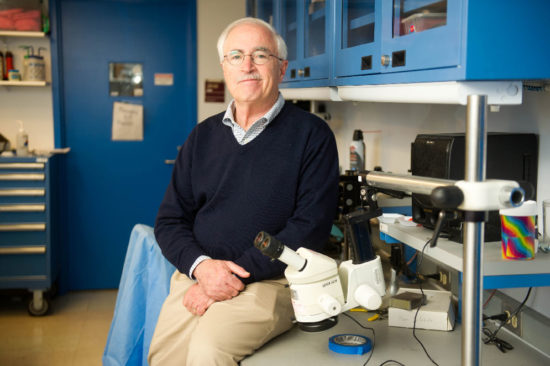

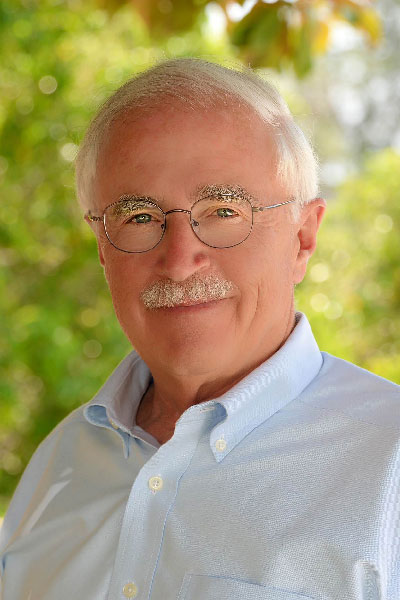

A memorial will be held this Thursday, October 5, for Howard Eichenbaum, a William Fairfield Warren Distinguished Professor and a College of Arts & Sciences professor of psychological and brain sciences. An internationally renowned figure in advancing the understanding of the fundamental nature and mechanisms of memory, Eichenbaum died on July 22 at age 69, following spinal surgery. The memorial, in the Trustees Ballroom at One Silber Way at 1 p.m., is open to the public.

Eichenbaum, director of BU’s Center for Memory and Brain and lab chief of the center’s Laboratory of Cognitive Neurobiology, studied the neuropsychology of memory in animals and the characterization of the memory-coding properties of neurons and was renowned for his groundbreaking work on the role of the hippocampus in the formation of memory.

Since his death, friends and colleagues have been remembering Eichenbaum as both a pioneering researcher and an inspiring mentor to students, postdocs, and junior faculty throughout his 21 years at BU.

BU Today reached out to some of Eichenbaum’s colleagues, asking them to talk about his work as a scientist and the impact he had on their lives.

Will Mau (MED’21), Laboratory of Cognitive Neurobiology

Howard Eichenbaum put masterful care into crafting his science. His experiments were about more than simply novel discovery. They were also about telling a complex and compelling story about the fundamental mechanisms of the brain. I distinctly remember lab meetings where he would judiciously dismantle and rearrange our presentations into more coherent forms. His love of clarity motivated all of us to analyze and depict our data in ways that painted the clearest possible picture.

Steve Ramirez (CAS’10), CAS assistant professor of psychological and brain sciences

I’d almost quit research because my first lab experience was miserable, and then I joined Howard’s lab. Howard was a walking encyclopedia and a very nice guy, who happened to love the Red Sox and baseball, which we got along over endlessly. And I was like, this is what research can be like? You can be a nice dude and also do kickass science?

I was in his lab for two years. I did my undergraduate thesis in his lab. At first, I would rehearse what I wanted to say to him, because I didn’t want to sound stupid.

Howard was the outside person on my thesis committee at MIT, and on the day of my graduation, he came up to me and said, “There might be a job opening in a year or two. Keep an eye out, because we’d love to have you.” Last fall we were in Washington, D.C., having this great conversation over a beer, and he was like, “I wouldn’t be doing my job if I didn’t tell you that BU has a faculty search going on right now; we are looking for a systems neuroscience person similar to what you’re doing, and I would strongly recommend you apply if you’re interested.” And happily, it worked out.

Howard walked up and down the lab all the time and talked to people about: “How’s that experiment going?” or an idea he had. At first it was intimidating how much this person knows about everything. But then you start reading more and more and realizing you really care about this, and you’re never going to get bored. You reach that edge of what the field knows and doesn’t know, which he did a long time ago. It was amazing to see that and amazing to have that person talk to me in a way that I didn’t feel dumb. I would actually get excited about memory, where before I didn’t really know what it was. I still don’t know what it is, but that’s what gives us a career.

Denise Parisi, assistant director, Center for Memory and Brain

Having worked with Howard for 20 years, my memories are of a kind and thoughtful person, generous with his time and knowledge. He possessed boundless energy and was always honored to be invited to speak at universities and colleges around the world. He never wanted to say no to speaking invitations, and he could be in three different countries giving talks in one week, but always remembered to bring me back chocolates. His unwavering dedication and passion for his research are what made him such a success and his kind heart and love of life are what made him such a great man.

John Bladon (MED’18), Laboratory of Cognitive Neurobiology

I told Howard that I was hoping to become an industry researcher rather than a professor. I was pretty nervous, considering he was a strong-minded, well-established academic researcher. His response was at first somewhat disappointed, but he very quickly transitioned to listing off everybody he knew in industry. I left that meeting with about five references to call about industry jobs. I think this was reflective of his attitude towards mentorship, in that his first reactions were always about the research, but in the back of his mind he knew that the progress of the students was paramount.

Gloria Waters, BU vice president and associate provost for research

Howard held a high bar not only for his science, which was top-notch, but he also wanted the support for science at BU to be at the level it deserved given the quality of the work. One of the things that I liked and admired about him most was his honesty—if something was great he would let you know it, but if some area was not running as smoothly as he thought it should be or if he felt that we could be supporting his work in a better way, he was sure to let you know. However, he didn’t just complain—he always came with ideas, suggestions, and solutions, and he did so in a way that made you want to work with him to find a solution. In addition, if asked, he was willing to contribute to help turn things around. One of the prime examples I can think of is that he had many ideas about how our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee could be better. He came to see me to air his concerns. We decided that it did need improvement, but that we could only do that if it had a strong faculty chair. We asked him to serve as chair, and he played a really important role at a critical time in helping us restructure the committee to better support the faculty.

David Sullivan, postdoctoral associate, Laboratory of Cognitive Neurobiology

One of the less well-known aspects of Howard’s scientific approach was his recent push toward new techniques. When I interviewed with Howard for my postdoctoral position in 2013, the thing that excited me the most was that he had just invested in equipment to monitor neurons in freely moving mice via imaging, and needed someone to help spearhead the adoption of this new technique. Compared to recording with wires, the imaging technique allows one to two orders of magnitude more neurons to be monitored simultaneously, over time periods of weeks instead of days. Howard saw that this new technique opened up realms of scientific questions that were difficult and/or impossible to address previously, and it’s a tragedy that he didn’t live to see the results.

Michael Hasselmo, director, Center for Systems Neuroscience, and CAS professor of psychological and brain sciences

I remember first meeting Howard when he spoke at Harvard when I was a junior faculty member in the department of psychology there. Howard strode into my office, speaking at a faster speed than most other human beings, and in his typical generous manner, he rapidly advised me to contact the program officer and select the study section at the National Institute of Mental Health that led to the funding of my first National Institutes of Health grant.

Howard Eichenbaum also wrote faster than anyone I know, and yet maintained an admirable lucidity of prose that manifested in his many papers and books, influencing the direction of the field and inspiring generations of young researchers.

Howard’s energy levels amazed me. Even at age 69, he had seemingly boundless sources of energy. Losing him, it seems as if the field lost two or three scientists.

Nathaniel Kinsky (MED’19), Laboratory of Cognitive Neurobiology

In my numerous discussions with Howard, I discovered that his passion for science was exceeded by that for his family. One conversation in particular sticks out, from the day I told him my wife was pregnant with our second child. He congratulated me, then told me in the same excited tone he normally reserved for the hippocampus that as best he could figure, each child required 1.5 adults to care for it. He then walked me through the math and what that meant for me and my wife by counting on his fingers. “Two kids times one point five adults per kid equals three adults. Then there is you and your wife. Looks like you are short one adult.” My daughter was born a few weeks after Howard died, and as I claw my way through the first weeks of her life, I’m struck by how right he was.

A memorial for Howard Eichenbaum will be held on Thursday, October 5, from 1 to 2:30 p.m. in the Trustees Ballroom, One Silber Way. Family members, friends, and colleagues from throughout Eichenbaum’s life will speak, followed by a reception. The memorial is open to the public. In addition, BU will host an academic retrospective on March 23, 2018, where scientists from around the world will address various aspects of Eichenbaum’s research. That event will also be open to the public.

Memorial gifts may be made to the Professor Howard Eichenbaum Undergraduate Neuroscience Fund at Boston University. Gifts by mail should include a note designating the Eichenbaum Fund, with checks payable to Trustees of Boston University and mailed to: Boston University Gifts & Records, 595 Commonwealth Avenue, Suite 700, Boston, MA 02215. Online gifts may be made here. Click on give to BU, then on Other Fund under Cause, and write Eichenbaum Fund in the text box.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.