Rachael Johnson

Read the instructor’s introduction

Read the writer’s comments and bio

Download this essay

Depicting Perspective Shifts in Graphic Memoirs vs. Oral Storytelling Narratives

While graphic memoirs and oral storytelling narratives present vastly different mechanisms for creative self-expression, they still have many technical elements in common. For example, both graphic memoirs and oral storytelling narratives allow the storyteller to zone in on a specific event, time span, or relationship with a place, person, or object, and their feelings surrounding it. For instance, Alison Bechdel’s award-winning graphic memoir, Fun Home, focuses primarily on Bechdel’s complicated relationship with her father. Meanwhile, David Small delves into his struggles growing up with physical disability and emotional neglect in Stitches. My own graphic memoir, entitled Hello, Hometown, is based on an oral storytelling I performed previously, which examined my childhood perspective on my hometown of Houston, Texas, and how it changed when I moved to Hawaii as an adolescent. I utilize differences in artistic detail and color contrast coupled with expository text and dialogue throughout Hello, Hometown in order to visually convey the same shift in perspective I communicated in my oral account of the same story.

Since Hello, Hometown focuses primarily on my character Rachael’s relationship with the city of Houston, I wanted to make sure I painted a thorough picture of it within the mind of the reader from the very beginning. In Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud describes the importance of aspect-to-aspect transitions when introducing a setting. “Aspect-to-aspect transitions,” he states, “bypass time for the most part, and set a wandering eye on different aspects of a place, idea, or mood” (72). With this in mind, I began Hello, Hometown by discussing and illustrating the various prominent features of Houston that I opened with in my original oral storytelling presentation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

McCloud also acknowledges comics that combine simply-drawn characters with unusually realistic backgrounds in the second chapter of Understanding Comics. “This combination,” he declares, “allows readers to mask themselves in a character and safely enter a sensually stimulating world” (43). While my setting illustrations aren’t necessarily realistic, I draw them with more detail than I do the characters involved in the story. Since Rachael’s struggles with homesickness and adapting to a new environment are sentiments that many individuals can relate to, I hoped that readers would commiserate more with her if I opted for a less realistic drawing style when depicting her expressions in any given scene.

Nonetheless, during the initial planning stages of my graphic memoir, I actually had trouble coming up with specific anecdotes that accurately and effectively conveyed the story I wanted to tell. This is because I focused more on my thoughts and feelings in my oral storytelling presentation and less on concrete scenarios that were easy to visually render. I eventually understood through the revision process the extent to which the graphic memoir genre utilizes the comic medium to portray immediate experiences instead of merely describing them as one does in oral storytelling.

In the final draft of Hello Hometown, I employ both dialogue-based scenes and textual explanations with accompanying illustrations in order to drive the story forward. My most substantial revision consisted of changes to the phone conversation scene in the middle of the graphic memoir. In this scene, Rachael and a friend discuss Rachael’s disillusionment with Hawaii after she moved there, as well as the various aspects of life in Houston that she took for granted before she left. This section was significantly shorter in my first draft—in fact, it only consisted of the two panels at the bottom of page 3 (Fig. 2). I later realized I could foster an increased sense of intimacy between Rachael and the reader by adding additional panels that extended the conversation to include additional related subject matter. This allowed me to more effectively depict Rachael’s homesickness as she felt it in the moment, rather than exclusively portray it through a retrospective lens, as I had during my oral storytelling presentation.

Fig. 2

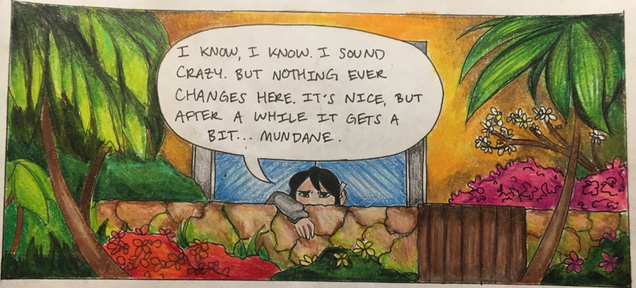

The phone conversation concludes with the large panel at the top of page 5. In this panel, I used both Rachael’s verbal commentary and grayscale coloring to visually juxtapose her unhappiness and the stunning beauty of her surroundings (Fig. 3). “Nothing ever changes here,” she grumbles. “It’s nice, but after a while it gets a bit…mundane” (5).

Fig. 3

Of course, Hawaii’s tropical scenery isn’t visually mundane in the slightest. Certain aspects of island life—such as bad traffic and repetitious weather patterns—are instead what she perceives to be monotonous and mundane about Hawaii. In Hello, Hometown, Rachael realizes that it’s the opposite in Houston only after moving away: what Houston lacks in surface-level beauty, it makes up for in the understated vibrancy of its residents’ lifestyles. I visually depicted this perspective shift in the vastly different portrayals of the Houston skyline on pages one and six, despite the obvious car ride parallel (Fig. 4 and 5).

Fig. 4 Fig. 5

The city itself remained the same throughout the time-skip. Rachael’s perception of it was all that changed, similarly to how I communicated my actual experience in the orated version of the same story.

Graphic memoirs and oral storytelling narratives are extremely different forms of creative communication—the first conveys information solely through visuals accompanied by text, while the second does so exclusively through verbal anecdotes and descriptions. Nonetheless, it is indeed possible to translate a single story effectively between the two mediums because they possess many technical similarities.

Works Cited

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York, William Morrow Paperbacks, 1994.