Matthew Yee

Read the instructor’s introduction

Read the writer’s comments and bio

Download this essay

From drivers’ licenses to passport books, identification documents are seemingly nondescript. Today, the photos on these documents are accepted as simple conventions of record-keeping, enforced for public accountability. These innocuous shots don’t criminalize their subjects; rather, they convey appearance. However, identification documents have a history fraught with racial and political complication. Even though certificates today assert a person’s identity and citizenship, immigration documents during the Chinese Exclusion Era functioned to mark a person’s perpetually foreign status. For Chinese immigrants, their path wasn’t easy.

Beginning in the early 1880s, Chinese immigrants from the Kwangtung[1] region of China began immigrating to California. Colloquially referring to their destination as “gold mountain,”[2] they hoped to support their families at home. As professor of history Sue Fawn Chung explains, the Kwangtung region was strife with civil conflicts and natural disasters in the late nineteenth century (Chung 5). Correspondingly, Chinese immigrants saw America as a place of opportunity. When they arrived, they were met with unforgiving laws regarding citizenship papers. Immigrants and their photos were inescapably conjoined, since newcomers were required to carry identification cards at all times.[3] Yet, these portraits were also influential tools—since immigration officers associated individuals with their portraits, the portraits became associated with social status. With this newfound influence, immigrants could surpass barriers at the border. Therefore, Chinese immigrants countered degrading government-issued photographs during the Exclusion Era; by altering their portraits to include signs of individual identity and orchestrating multiple shots to display family cohesion, they effectively reclaimed the power of their enforced documentation.

Colonial photography from the Kwangtung region influenced Western perspectives of China and highlighted photography’s potential as a “tool” to label ethnic groups. With the impending decline of the Qing dynasty in the late eighteenth century, China was forced to open ports to foreign traders at Hong Kong (Kent 3).[4] However, what resulted was much more than a simple exchange of goods. Fueled by the allure of “the Orient,” missionaries and explorers selectively documented life in China with novel photographic technology. Their photos were far from complimentary. As art historian Sarah Fraser writes, “the continuous presence of devastating views of poor, displaced people from southern China contributed to the long-term traction of those photographs” (Fraser 42). By sharing photos of exclusively poor areas, colonists portrayed China as a place in desperate need of Westernization. As such, Americans began to view overseas Chinese immigrants as a societal and moral threat. Fraser also establishes the potential of photography as a “tool” to “mark and distinguish” individuals (Fraser 51). In this case, the tool was used to dehumanize others. These negative viewpoints translated to the Chinese Exclusion Act, when the American public denounced increases in immigration to U.S. shores.[5]

Emboldened by malicious colonial photography from Kwangtung, the U.S. government demanded the use of identification portraits to monitor Chinese immigrants. This monitoring was necessary because the Chinese Exclusion Act couldn’t be implemented as an absolute purge. As federal courts conceded, Chinese-American citizens were constitutionally entitled to remain (Berger 1225). In response, immigration officers held these citizens under even greater scrutiny. Historian Anna Pegler-Gordon examines this trend in her analysis of the Exclusion Era, noting that Chinese-American citizens were the first group of people mandated to carry identification cards with photographs (Pegler-Gordon 53). Being used to “mark and distinguish” citizens, these early pictures were not unlike criminal mug shots of the time. In many early portraits, immigrants could be seen holding placards with identifying numbers (Luibhéid 57). With height charts behind them and numbers in front, they were essentially in jail. However, such portraits weren’t consistently controlled. Over time, U.S. ports relaxed their policies—and the immigrants discovered a loophole.

With changing policies on the regulations for portrait-taking, Chinese immigrants found an unprecedented opportunity to display overt wealth in their photos. In turn, this illusion helped to assert their individual identity and undermine the immigration process. While early photos were highly regulated, taking portraits on-site quickly became a mounting financial struggle for U.S. ports. As such, immigrants became responsible for procuring their own photos—they were permitted to bring portraits to their entry interrogations. Selecting a picture would be crucial, as physical presentation could determine an immigrant’s fate. Historian Erika Lee summarizes this trend, noting that officers usually admitted more merchants than general laborers (Lee 86). The merchants, officers reasoned, would likely seek out Chinese consumers. In this way, they would not interfere with the American workforce. Since merchants were usually well-dressed and finely decorated, officers were quite confident in their abilities to distinguish them from the laborers. Chinese immigrants recognized this mindset and in turn altered their photographs. Thus, the photographs became “tools” for constructing identity. One such portrait is below.

Fig. 1. Affidavit of Leong Shee from the Exclusion Era, with Identifying Photograph. Leong Shee’s affidavit photo, in detail and in original position (USDOJ “Affidavit” 05).

Rather than include a standard headshot with her affidavit, Leong Shee attached a full portrait. The photo could barely fit on the page; it almost blocked the various signatures. Wearing elaborate clothing, Leong Shee sits next to a table with a bookstand, vase, and flowers.[6] In her hand she holds a book, signifying her education. But, those statements of wealth aren’t simply meant to help with her identification. Instead of including a photo of procedure, Leong Shee included a portrait of status. Author Eithne Luibhéid identifies this common phenomenon, writing that Chinese women needed to appear sophisticated in their photos since the American public commonly viewed them as morally vulgar (Luibhéid 46). If U.S. officials deemed an individual non-reputable, that individual wouldn’t be permitted entry. To overcome this hurdle, Chinese immigrants wore their best clothes and created elaborate displays for their portraits. By doing so, they created more respectable identities for themselves. Thus, the photos shifted in purpose from identifying markers to messages of prestige.

While Leong Shee and others asserted prestige and individuality through their heritage-rich portraits, others used their photos to demonstrate Westernization. Since Chinese immigrants were often seen as a threat to the integrity of American culture, those who had assimilated were more likely to be admitted. Consequently, many immigrants hid signs of Chinese culture in their official portraits. An example of this effort is shown below.

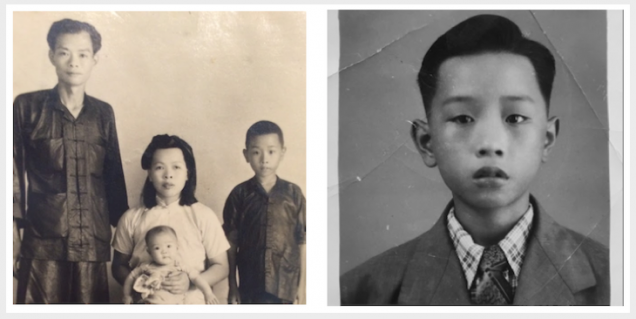

Fig. 2. From the Author: Family Portraits taken in Nam Lung Village, Kwangtung, China. On the left, a 1946 family portrait (Wong). On the right, a 1952 passport portrait (Wong). Notice that the young boy[7], appears in both photos.

On the leftmost side is Wong Jang, who had moved to Boston in the 1930s. Hoping that his son might join him, Wong had his son’s portrait taken and forwarded to the U.S. embassy. The two photos in Figure 2 were from the same album, and taken a few years apart. However, only the photo on the right was sent to the embassy. By appealing to American standards through the use of Western garments, Wong strengthened his son’s application. After all, U.S. immigration officers were wary of young children, as they would often be placed in local schools to integrate with American society. By hiding culture, an immigrant could sway border officers.

In addition to clothing, other immigrants altered their grooming styles to become more Westernized with the hopes of improving their cases during interrogations. Wong Kim Ark[8], a native-born American citizen, won a case against the U.S. Supreme Court to assert his citizenship status. As legal scholar Bethany Berger outlines, Wong Kim Ark’s photographs all display his partially shaved scalp, indicating the presence of a queue hairstyle (Berger 1228). However, in both his front and side profile portraits, his queue is hidden. By concealing that sign of foreign identity, Wong Kim Ark improved his image for the Court.

Both Wong Jang and Wong Kim Ark may appear to have capitulated to standards of Westernization, but the context of their photos actually reveals more enhanced individual identity. Even though the young boy’s Western portrait was sent to the embassy, his photo in traditional clothing occupied a prominent place in the family album. Similarly, Wong Kim Ark hid his queue without cutting it off. Despite outward appearances, the two kept their true cultural identities intact. Both individuals subverted the purpose of realistic photography to “mark and distinguish” themselves, and instead used the photographs as “tools” to improve their immigration cases. Thus, this duality of image represents a strengthening of individual identity, complete with expressions of both American and Chinese customs. Just as Leong Shee’s photo functioned as more than simple identification, these portraits had changed from identifying markers to impressions of individuality. Just as importantly, the portraits could be altered to represent family unity.

In addition to reinforcing individual expression, immigration photos were often repurposed to maintain family cohesion despite geographic separation. Family connection was one of the most important facets of social identity in China, and this translated to overseas family dynamics as well (He 3). Because the Exclusion Act’s policies included strict penalties for even the slightest discrepancies in testimony, Chinese-American citizens often failed in the sponsorship process for their relatives. In the hopes of preserving their family unit, these citizens repurposed their failed applications to create unconventional scenes. Some examples are shown below.

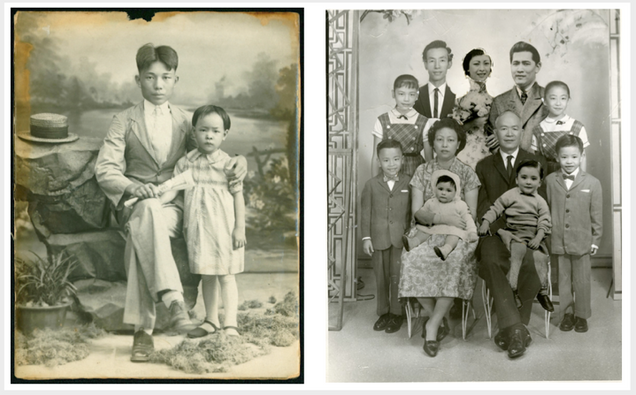

Fig. 3. Peculiar Photographic Adjustments in Family Records. On the left, a 1926 portrait from Kwangtung[9] (Jew 26). Note that the man’s head is awkwardly oversized—a clear sign of editing. On the right, a 1961 portrait from New York (Low 61). The head of the woman in the back is disastrously pasted in.

The photo on the left with two siblings is from Kwangtung. While the young girl was in the studio when the portrait was taken, her brother was not. A few years earlier he had moved to the U.S. Because of his laborer status, he was not granted a passport, and thus wouldn’t be allowed to travel between countries. With better work prospects in America, he stayed. Close viewers will note that his head appears quite large and his body unusually androgynous. In fact, he wasn’t there at all—he simply sent back his voided passport application to be included. An aunt sat in his place, imitating what was missing from the headshot.

The photo on the right demonstrates a similarly striking repurposing of immigration photos. Taken in New York, this portrait represents an idealized family in unity. However, the couple in the back and their children in the front row were crudely pasted in. That sibling’s family had attempted to immigrate from Hong Kong to America, but due to a small mistake on an application form their petition was denied (Low 61). With no choice but to remain in Hong Kong, that sister sent her family’s application portraits to New York, where they were added to the family shot. Both sets of alterations can hardly be recognized as passport photos; the adjustments created a new meaning. Thus, this process helped to assert a stronger “identity during [that] period of intense upheaval” (Kent 1). In the portraits, the family could be as one.

Other immigration photos weren’t altered from multiple sources, but were instead used to emphasize the power of individual portraits in family settings. In Kwangtung, a common funerary tradition involved hanging memorial portraits in the home (Lee 92). For stylistic and economic reasons, immigration portraits were commonly used for this purpose. After all, immigration portraits were often the finest representations of their subjects. Immigrants rarely, if ever, needed to imitate that level of material wealth after their arrival. Other times, these portraits were the only chronicle of their subjects—photography was still an expensive commodity up until the 1960s. An example of this reclaiming is shown below.

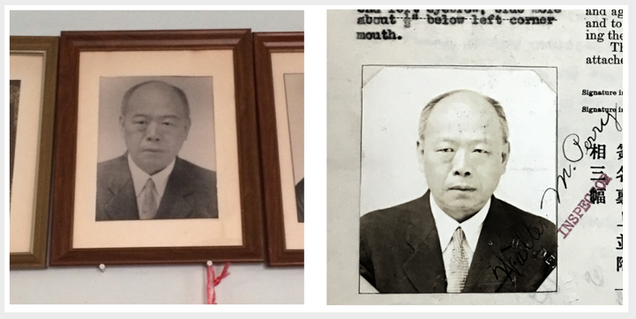

Fig 4. From the Author: Portraits of Wong Yick[10] in multiple contexts. On the left, a replication of Wong Yick’s immigration portrait (Wong 51). The same photo also appears in a 1933 citizenship file, on the right (USDOJ “File” 33).

Wong Yick’s portrait appears in two places: a US entry record and his grandson’s house. In that immigration permit, an officer had scribbled a signature over the shot, demonstrating its lack of aesthetic value. Wong’s portrait was badly overexposed in his file, further representing its lack of importance. However, the same photo appears quite differently in a family setting. In the house, the photo wasn’t part of a document but was instead a commemorative family item. Pegler-Gordon comments on this practice, arguing that such reclaimed presentations “changed the purpose of the photograph from the identification of an unknown laborer to the intimate recognition of a familiar face” (Pegler-Gordon 74). By extracting the photo from its document source, family members reconstructed its presence. No longer a criminal snapshot to “mark and distinguish,” the portrait became a strong indicator of family unity.

Today, identification cards are commonplace. An obvious and reassuring aspect of modern society, these documents offer transparent ways to identify people and verify their history. However, the portraits on these documents are historically complicated. Photographic identification was first introduced in America during the Exclusion Era, and it effectively criminalized the Chinese people. Chinese immigrants subsequently gained control of their photographs; they used them as tools of self-expression. To improve their chances of admission to the U.S., immigrants arranged their portraits to reflect a more idealized “self.” They also manipulated their immigration portraits to serve a more familial purpose. Photography was indeed a tool used by U.S. officers to control newcomers on American soil. But, photography also formed a powerful channel for personal expression. Chinese immigrants undermined the power of their enforced documentation; in using their photos, they prevailed. As author Roland Barthes reflects in his book Camera Lucida, “the photograph itself is in no way animated…but it animates me” (Barthes 20). In the same way, Chinese immigration portraits represented a pure illusion—but one powerful enough to alter reality.

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. New York, Hill and Wang, 1980.

Berger, Bethany R. “Birthright Citizenship on Trial: Elk v. Wilkins and United States v. Wong Kim Ark.” Cardozo Law Review, Vol. 37, No. 4, 2016, pp. 1185–1258.

Chung, Sue Fawn. “Tracing the History of Chinese American Families.” History: Reviews of New Books, Vol. 35, No. 1, 2006, pp. 5–10.

Fraser, Sarah E. “The Face of China: Photography’s Role in Shaping Image, 1860–1920.” Getty Research Journal, No. 2, 2010, pp. 39–52.

He, Yan. “Special Issue Introduction: Chinese American Archives, Collections, and Librarians.” Chinese America: History and Perspectives, Vol. 30, 2016, pp. 1–2.

Jew, Shee. Portrait of my Children. 1926, Hoy Ping, Kwangtung, China.

Kent, Richard K. “Early Twentieth-Century Art Photography in China: Adopting,

Domesticating, and Embracing the Foreign.” Trans Asia Photography Review, Vol. 3, No. 2, 2013.

Lee, Erika. At America’s Gates: Chinese Immigration During the Exclusion Era, 1882–1943. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

Low, Moo Gee. Low Family Portrait. 1961, Museum of Chinese in America, New York.

Luibhéid, Eithne. Entry Denied: Controlling Sexuality at the Border. Minneapolis, MN, University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

Pegler-Gordon, Anna. “Chinese Exclusion, Photography, and the Development of U.S. Immigration Policy.” American Quarterly, Vol. 58, No. 1, 2006, pp. 51–77.

United States Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service. Affidavit of Leong Shee in Support of Young Fui. San Francisco, 1905.

United States Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service. File of Wong Yick, Native. Boston, 1933.

Wong, Jang. Portraits of my Family. 1946–1952, Nam Lung Village, Kwangtung, China.

[1] Kwangtung is the historical Romanization of modern day Guangdong, China (廣東).

[2] California in the Kwangtung dialect is Gim San (金山), literally, “Gold Mountain.”

[3] Required under the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. While new immigrants were barred from American shores, Chinese-American citizens were allowed to stay. As such, they were permitted to sponsor their immediate relatives; this would eventually lead to huge influxes at U.S. ports. All photos in this paper are from the time period when that law was in effect: 1882-1965.

[4] Hong Kong is immediately adjacent to Kwangtung in the southernmost part of China.

[5] This occurred in the wake of the Great San Francisco earthquake in 1906. A majority of San Francisco city records were destroyed in subsequent fires, including birth records. In response, a majority of Chinese immigrants immediately registered as citizens by birth. With no choice but to accept their claims, U.S. ports accepted these early immigrants. Using their “citizen” status, many sponsored their relatives to America.

[6] Leong Shee’s portrait was likely exaggerated regarding her wealth. In her affidavit, she remarked that her homeland was in Kwangtung, China. Given the economic turmoil of the time, such a level of wealth would have been exceedingly rare (and dangerous to maintain).

[7] From Fig. 2, the young boy is the author’s grandfather.

[8] Wong Kim Ark is not related to the author.

[9] Jew Ngan is the young girl on the left-side photo in Fig. 3. She is the author’s great-grandmother.

[10] From Fig. 4., Wong Yick is the author’s great-great-grandfather.