Remote Teaching and Learning in the Time of COVID-19

Remote Teaching and Learning in the Time of COVID-19

Remote Teaching and Learning in the Time of COVID-19

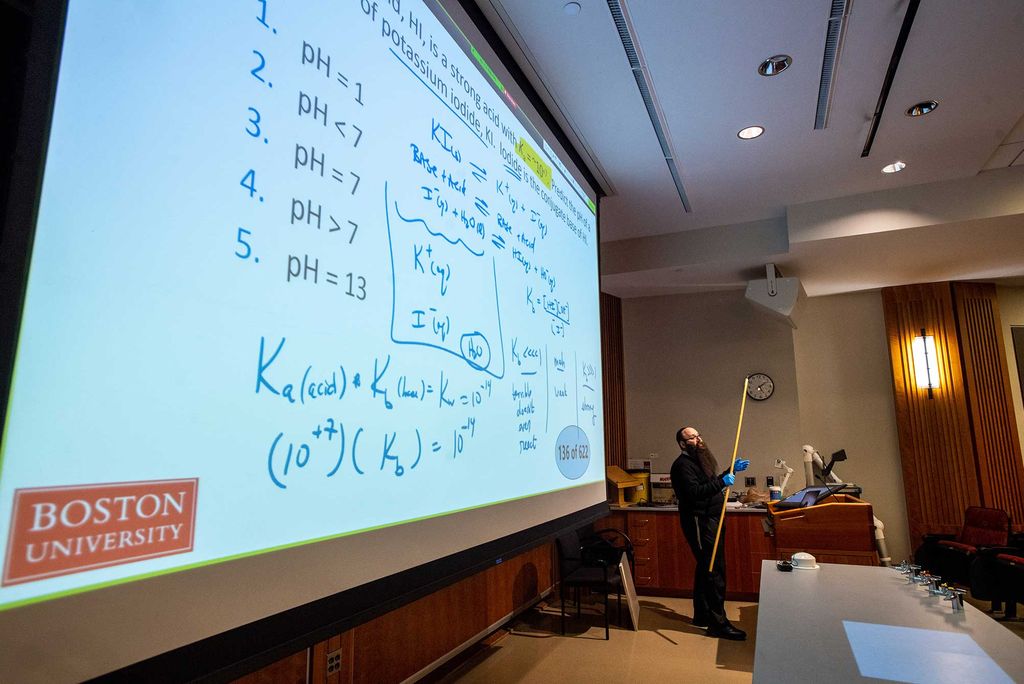

Binyomin Abrams, a striking figure with his long black beard, black hat, black slacks, and black cardigan, strides into his lecture hall on the first floor of an eerily deserted science building on Commonwealth Avenue and pulls on a new pair of electric blue disposable surgical gloves.

Retrieving a handful of Clorox disinfectant wipes from the jumbo-sized dispenser in his plastic sack, the College of Arts & Sciences master lecturer and director of general chemistry scrubs down his podium and the smart screen on top of it, his laptop and table, and his stylus. He trades in his blue gloves for a fresh pair, reaches across the freshly cleaned keyboard of his laptop and presses the icon for Zoom.

It’s a couple of minutes before 5 pm on the first Tuesday after spring break, the start of Abrams’ first Chemistry 102 lecture in BU’s new coronavirus-era remote teaching and learning world. And he’s going to give the day’s lecture on the structure of acids and bases—to an empty classroom.

It’s a scene playing out in lecture halls across BU, in makeshift home offices in Boston and its suburbs, across the commonwealth, New England, the country, and the world, as armies of scholars and professors carry on, reconnecting with their students via technology they’re scrambling to master amid the global pandemic. It’s perhaps the biggest experiment in higher education in modern times.

“Normally, this is where I’d be walking around, talking to students I haven’t seen in a week and a half—‘How was your spring break,’ ‘The airlines are always obnoxious,’” Abrams says, smiling wryly from behind his beard. “I’m here talking to myself in an empty lecture hall, with 260 seats.”

He was supposed to have one of his graduate student teaching fellows here to help him field questions via the Chat field that Zoom provides. But that was last week. Now, with the urgent need for social distancing, he has ordered his teaching fellow to stay home.

“Forty-five seconds!” he calls out, checking his watch. “How many students are logged in—163, we’re getting close.” Within seconds, the count climbs to 181—181 undergraduates Zooming in from Boston, New York, Chicago, Seattle, Los Angeles, from their bedrooms, kitchens, family rooms, basements, and makeshift alcoves in multiple time zones and countries. A few students can’t connect yet—they’re still trying to make it back to their families in the Middle East and Asia.

“Welcome back from spring break,” Abrams booms, looking out at the rows of empty rust-colored seats. “To those of you in California, to those of you where it’s 3 am, you are my heroes, thank you for coming. It’s pretty lonely here in Boston. I miss having you in class. You have no idea how weird and empty this is.”

These students are paying a lot of money to learn chemistry. President Brown asked that we continue classes synchronously as much as possible. We can do this.

He’s explained in earlier emails that because there are so many students, and limited bandwidth, they will have to turn off their video and audio and type their questions and answers via Chat, which he will read on his laptop. They can’t see him, but they can hear his voice—and Abrams is projecting with his usual vigor, as if he’s trying to reach students in the back rows and not over the internet via the microphone attached to the podium. The students can see the oversized screen behind him, where his written questions and equations will appear.

“We’re going to try to do this as normally as we can,” he says. “If something goes wrong, yell at me.” In a nanosecond, chuckling to himself, he realizes that every one of 181 students has already turned off their audio, as he directed them to do. “Of course I won’t be able to hear you.”

Things do go wrong—but little things. Just as he’s launching into the day’s discussion, a question pops up in Chat. “Somebody says they can’t hear anything,” he says, gesturing at his laptop with his blue-gloved hands. “If you can’t hear anything, you have to join the audio, but stay muted…can you hear now?”

Again, he corrects himself: “Of course, they can’t hear me tell them what to do—they can’t hear me.”

As he writes with his stylus on the smart screen, his words are projected on the screen behind him: “Join the audio. Stay muted. Can you hear me now?”

The student signals via Chat that he can now hear Abrams. “Great,” his teacher says, waving his blue-gloved hands in the air. “Small victories.”

Abrams, who is trained in theoretical chemistry and conducts research in the field of chemical education, holds one of BU’s highest teaching honors, a Metcalf Award for Excellence in Teaching. With his passion for making chemistry fun—that means doing away with obfuscating, soul-numbing jargon—he was cited for his enthusiasm, innovation, and gift for communicating science, all of which he is applying to his new role: Professor of Zoom.

BU is offering plenty of online assistance through Digital Learning & Innovation, the remote teaching coordinators (RTC) designated for each of its schools and colleges, and Information Services & Technology. But the tech-savvy Abrams, who has been recording his lectures for students for a number of years and had already joined a few Zoom calls and webinars, picked up Zoom teaching fairly quickly.

How did he learn so fast? “I guess I did what I ask my students to do—I was adventurous and played around until I felt like I understood what was going on,” he says.

Karen Allen, chair of the chemistry department, alerted faculty in an email that Abrams was available for help. He’s posted simple videos that tell you how to teach via Zoom. He churned out a six-page training manual, pulling all-nighters to do it. He met with his graduate student teaching fellows, as well as colleagues, to make sure they could cover all their regular office hours, from 9 am to 5 pm, from their homes. He’s holding his office hours from a nook next to the laundry in his 1,600-square-foot condo in Brighton, which he shares with his wife, Liorah, a graphic designer who works from home, and their four daughters, ages 20 months to 12 years. He and his wife have deputized the two older girls, who are now doing remote learning themselves on their Chromebooks, as parent assistants.

His secret weapon? “I have enough espresso pods in my house to choke a cow,” Abrams says. “Espresso.com—next day delivery. If we run out of coffee, they’ll have to shutter the University.”

“These students are paying a lot of money to learn chemistry,” he says. “President Brown asked that we continue classes synchronously as much as possible. We can do this.”

And so they are.

Premed student Emma Hartman (ENG’23) is now taking Chemistry 102 from her Canton, Mass., bedroom. Her parents and her two brothers—the older one is home from Georgetown University, the younger one is in high school—are now all working, or studying remotely, at home, like her. She printed out her academic schedule for the family—“so they know not to yell out for me when I’m in class.”

She couldn’t figure out Chat in time for the lecture, she says, and she missed seeing Abrams running up and down the rows of seats. But his passion for teaching still came through. “He’s such a dynamic speaker,” she says. “I feel sorry for the professors. Some people are saying, ‘I didn’t sign up to take classes online.’ The professors didn’t, either.”

I appreciate the fact that he was still very high-energy. He kept us entertained during that hour and 15 minutes, but actually learning.

Justin Chan (CAS’23), also a premed, was Zooming in from his bedroom in Milton, Mass., which is still decorated with his elementary school vintage stickers. “I told my parents I was going to be in my room and if they want to contact me, they should text me,” he says. “I didn’t want them barging in while I was in class.”

He gives Abrams high ratings. “I appreciate the fact that he was still very high-energy,” Chan says. “He kept us entertained during that hour and 15 minutes, but actually learning.”

Kathleen Mahoney (ENG’23) was joining the class from a desk she’d commandeered in the basement of her family’s home in upstate New York, with her cat, Sorcha, underfoot. “It wasn’t as weird as I thought it would be,” she says. “I had two days of classes to get used to it. My heart goes out to the students who can’t go home.”

Back in the lecture hall, Abrams is waving his arms in the air and responding to his students’ answers via Chat: “Awesome! Awesome! Awesome!”

“Cool!”

“A big thank you to everyone who’s answering questions. It makes me feel like I’m not talking to an empty room even though I’m talking to an empty room.”

In his nonexistent spare time, Abrams, a Hasidic Jew, is studying to be an ordained rabbi. Some of what he brings to teaching comes from Talmudic study, he says after the lecture. “The Talmud relates a story that the sage Rabbah would start any new class with words of jest—make a connection with your students that isn’t just content-related, but on a level that everyone gets: humor. Then, start teaching.”

Abrams’ religious training is especially relevant now, he says. “One of the lessons that Hasidic thought teaches us is that we must find and accentuate the positive in all situations—focusing on the positive, the good, brings about more good. I think we’re all trying to do that.”

At the podium in the empty lecture hall, he gives the students a few minutes to answer yet another question. “Talk amongst yourselves,” he says. “I’m not going to stop saying that, I’ve been saying that in this lecture hall for 12 years.”

A student asks, via Chat, if it’s okay to take a bathroom break. “Yes, but don’t take your laptop with you,” says Abrams.

The students offer encouragement via Chat: “You’ve got this.” “You’re doing a great job.”

As 6:15 pm approaches, Abrams begins wrapping up. He rubs his hands together and gazes with a wistful expression into his laptop screen: “I miss you all. I’m looking forward to seeing you Thursday. There’s still a quiz on Monday. Stop by for office hours. We’re all in this together.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.